Geoffrey of Monmouth was a cleric from Monmouth, Wales, and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography and the popularity of tales of King Arthur. He is best known for his chronicle The History of the Kings of Britain which was widely popular in its day, being translated into other languages from its original Latin. It was given historical credence well into the 16th century, but is now considered historically unreliable.

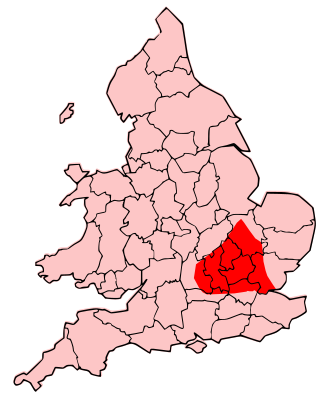

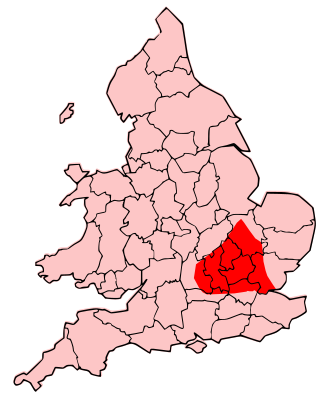

The Trinovantēs or Trinobantes were one of the Celtic tribes of Pre-Roman Britain. Their territory was on the north side of the Thames estuary in current Essex, Hertfordshire and Suffolk, and included lands now located in Greater London. They were bordered to the north by the Iceni, and to the west by the Catuvellauni. Their name possibly derives from the Celtic intensive prefix "tri-" and a second element which was either "nowio" – new, so meaning "very new" in the sense of "newcomers", but possibly with an applied sense of vigor or liveliness ultimately meaning "the very vigorous people". Their capital was Camulodunum, one proposed site of the legendary Camelot.

Lud, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth's legendary History of the Kings of Britain and related medieval texts, was a king of Britain in pre-Roman times who founded London and was buried at Ludgate. He was the eldest son of Geoffrey's King Heli, and succeeded his father to the throne. He was succeeded, in turn, by his brother Caswallon. Lud may be connected with the Welsh mythological figure Lludd Llaw Eraint, earlier Nudd Llaw Eraint, cognate with the Irish Nuada Airgetlám, a king of the Tuatha Dé Danann, and the Brittonic god Nodens. However, he was a separate figure in Welsh tradition and is usually treated as such.

The Catuvellauni were a Celtic tribe or state of southeastern Britain before the Roman conquest, attested by inscriptions into the 4th century.

Beli Mawr was an ancestor figure in Middle Welsh literature and genealogies. He is the father of Cassivellaunus, Arianrhod, Lludd Llaw Eraint, Llefelys, and Afallach. In certain medieval genealogies he is listed as the son or husband of Anna, cousin of Mary, mother of Jesus. According to the Welsh Triads, Beli and Dôn were the parents of Arianrhod, but the mother of Beli's other children—and the father of Dôn's other children—is not mentioned in the medieval Welsh literature. Several royal lines in medieval Wales traced their ancestry to Beli. The Mabinogi names Penarddun as a daughter of Beli Mawr, but the genealogy is confused; it is possible she was meant to be his sister rather than daughter.

Cunobeline was a king in pre-Roman Britain from about AD 9 until about AD 40. He is mentioned in passing by the classical historians Suetonius and Dio Cassius, and many coins bearing his inscription have been found. He controlled a substantial portion of south-eastern Britain, including the territories of the Catuvellauni and the Trinovantes, and is called "King of the Britons" by Suetonius. He appears to have been recognized by Roman emperor Augustus as a client king, as testified by the use of the Latin title Rex on his coins. Cunobeline appears in British legend as Cynfelyn (Welsh), Kymbelinus or Cymbeline, as in the play by William Shakespeare.

Tasciovanus was a historical king of the Catuvellauni tribe before the Roman conquest of Britain.

Cassivellaunus was a historical British military leader who led the defence against Julius Caesar's second expedition to Britain in 54 BC. He led an alliance of tribes against Roman forces, but eventually surrendered after his location was revealed to Julius Caesar by defeated Britons.

Nennius is a mythical prince of Britain at the time of Julius Caesar's invasions of Britain. His story appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain (1136), a work whose contents are now considered largely fictional. In Middle Welsh versions of Geoffrey's Historia he was called Nynniaw.

Historia regum Britanniae, originally called De gestis Britonum, is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It chronicles the lives of the kings of the Britons over the course of two thousand years, beginning with the Trojans founding the British nation and continuing until the Anglo-Saxons assumed control of much of Britain around the 7th century. It is one of the central pieces of the Matter of Britain.

Trinovantum is the name in medieval British legend that was given to London, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, when it was founded by the exiled Trojan Brutus, who called it Troia Nova, which was gradually corrupted to Trinovantum. The legend says that it was later rebuilt by King Lud, who named it Caer Lud after himself and that the name became corrupted to Kaer Llundain and finally London. The legend is part of the Matter of Britain.

Julius Asclepiodotus was a Roman praetorian prefect who, according to the Historia Augusta, served under the emperors Aurelian, Probus and Diocletian, and was consul in 292. In 296, he assisted the western Caesar Constantius Chlorus in re-establishing Roman rule in Britain, following the illegal rules of Carausius and Allectus.

Welsh mythology consists of both folk traditions developed in Wales, and traditions developed by the Celtic Britons elsewhere before the end of the first millennium. As in most of the predominantly oral societies Celtic mythology and history were recorded orally by specialists such as druids. This oral record has been lost or altered as a result of outside contact and invasion over the years. Much of this altered mythology and history is preserved in medieval Welsh manuscripts, which include the Red Book of Hergest, the White Book of Rhydderch, the Book of Aneirin and the Book of Taliesin. Other works connected to Welsh mythology include the ninth-century Latin historical compilation Historia Brittonum and Geoffrey of Monmouth's twelfth-century Latin chronicle Historia Regum Britanniae, as well as later folklore, such as the materials collected in The Welsh Fairy Book by William Jenkyn Thomas (1908).

Imanuentius is named in some manuscripts of Julius Caesar's De Bello Gallico as a king of the Trinovantes, the leading nation of south-eastern Britain at that time, who ruled before Caesar's second expedition to the island in 54 BC. Variant spellings include Inianuvetitius, Inianuvetutus and Imannuetitius. In other manuscripts this king's name is not given.

Quintus Laberius Durus was a Roman military tribune who died during Julius Caesar's second expedition to Britain. Caesar describes how soon after landing in Kent, the Romans were attacked whilst building a camp by the native Britons. Before re-inforcements could arrive, Laberius was killed. His burial site is traditionally the earthworks of Julliberrie's Grave near Chilham.

The Ancalites were a tribe of Iron Age Britain in the first century BCE. They are known only from a brief mention in the writings of Julius Caesar. They may have been one of the four tribes of Kent, represented in Caesar by references to the "four kings of that region" and in the archaeological record by distinct pottery assemblages.

In the course of his Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar invaded Britain twice: in 55 and 54 BC. On the first occasion Caesar took with him only two legions, and achieved little beyond a landing on the coast of Kent. The second invasion consisted of 628 ships, five legions and 2,000 cavalry. The force was so imposing that the Britons did not dare contest Caesar's landing in Kent, waiting instead until he began to move inland. Caesar eventually penetrated into Middlesex and crossed the Thames, forcing the British warlord Cassivellaunus to surrender as a tributary to Rome and setting up Mandubracius of the Trinovantes as client king.

The Bibroci were a tribe of Iron Age Britain in the first century BCE. They are known only from a brief mention in the writings of Julius Caesar. They may have been one of the four tribes of Kent, represented in Caesar by references to the "four kings of that region" and in the archaeological record by distinct pottery assemblages.

The Cassi were a tribe of Iron Age Britain in the first century BCE. They are known only from a brief mention in the writings of Julius Caesar. They may have been one of the four tribes of Kent, represented in Caesar by references to the "four kings of that region" and in the archaeological record by distinct pottery assemblages.

Fuimus Troes is a verse drama attributed to Jasper Fisher about Julius Caesar's invasion of Britain in 55 BC. It was published in quarto in London, 1633. The drama is written in blank verse, interspersed with lyrics; Druids, poets, and a harper are introduced, and it ends with a masque and chorus.