Related Research Articles

Excalibur is the mythical sword of King Arthur that may possess magical powers or be associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. Traditionally, the sword in the stone that is the proof of Arthur's lineage and the sword given to him by a Lady of the Lake are not the same weapon, even as in some versions of the legend both of them share the name of Excalibur. Several similar swords and other weapons also appear within Arthurian texts, as well as in other legends.

King Arthur, according to legends, was a king of Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

Geoffrey of Monmouth was a Catholic cleric from Monmouth, Wales, and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography and the popularity of tales of King Arthur. He is best known for his chronicle The History of the Kings of Britain which was widely popular in its day, being translated into other languages from its original Latin. It was given historical credence well into the 16th century, but is now considered historically unreliable.

Creiddylad, daughter of King Lludd, is a minor character in the early medieval Welsh Arthurian tale Culhwch ac Olwen.

The History of the Britons is a purported history of early Britain written around 828 that survives in numerous recensions from after the 11th century. The Historia Brittonum is commonly attributed to Nennius, as some recensions have a preface written in that name. Some experts have dismissed the Nennian preface as a late forgery and argued that the work was actually an anonymous compilation.

In the Matter of Britain, Igraine is the mother of King Arthur. Igraine is also known in Latin as Igerna, in Welsh as Eigr, in French as Ygraine, in Le Morte d'Arthur as Ygrayne—often modernised as Igraine or Igreine—and in Parzival as Arnive. She becomes the wife of Uther Pendragon, after the death of her first husband, Gorlois.

Bedivere is one of the earliest characters to be featured in the legend of King Arthur, originally described in several Welsh texts as the one-handed great warrior named Bedwyr Bedrydant. Arthurian chivalric romances, inspired by his portrayal in the chronicle Historia Regum Britanniae, portray Bedivere as a Knight of the Round Table of King Arthur who serves as Arthur's marshal and is frequently associated with his brother Lucan and his cousin Griflet as well as with Kay. In the English versions, Bedivere notably assumes Griflet's hitherto traditional role from French romances as the one who eventually returns Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake after Arthur's last battle.

Beli Mawr was an ancestor figure in Middle Welsh literature and genealogies. He is the father of Cassivellaunus, Arianrhod, Lludd Llaw Eraint, Llefelys, and Afallach. In certain medieval genealogies, he is listed as the son or husband of Anna, cousin of Mary, mother of Jesus. According to the Welsh Triads, Beli and Dôn were the parents of Arianrhod, but the mother of Beli's other children—and the father of Dôn's other children—is not mentioned in the medieval Welsh literature. Several royal lines in medieval Wales traced their ancestry to Beli. The Mabinogi names Penarddun as a daughter of Beli Mawr, but the genealogy is confused; it is possible she was meant to be his sister rather than daughter.

The Battle of Camlann is the legendary final battle of King Arthur, in which Arthur either died or was fatally wounded while fighting either alongside or against Mordred, who also perished. The original legend of Camlann, inspired by a purportedly historical event said to have taken place in the early 6th-century Britain, is only vaguely described in several medieval Welsh texts dating from around the 10th century. The battle's much more detailed depictions have emerged since the 12th century, generally based on that of a catastrophic conflict described in the pseudo-chronicle Historia Regum Britanniae. The further greatly embellished variants originate from the later French chivalric romance tradition, in which it became known as the Battle of Salisbury, and include the 15th-century telling in Le Morte d'Arthur that remains popular today.

Historia regum Britanniae, originally called De gestis Britonum, is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It chronicles the lives of the kings of the Britons over the course of two thousand years, beginning with the Trojans founding the British nation and continuing until the Anglo-Saxons assumed control of much of Britain around the 7th century. It is one of the central pieces of the Matter of Britain.

In Arthurian legend, Gorlois of Tintagel was the Duke of Cornwall. He was the first husband of King Arthur's mother Igraine and the father of her daughters, Arthur's half-sisters. Her second husband was Uther Pendragon, the High King of Britain and Arthur's father, who marries her after killing him.

This is a bibliography of works about King Arthur, his family, his friends or his enemies. This bibliography includes works that are notable or are by notable authors.

Octa was an Anglo-Saxon King of Kent during the 6th century. Sources disagree on his relationship to the other kings in his line; he may have been the son of Hengist or Oisc, and may have been the father of Oisc or Eormenric. The dates of his reign are unclear, but he may have ruled from 512 to 534 or from 516 to 540. Despite his shadowy recorded history Octa made an impact on the Britons, who describe his deeds in several sources.

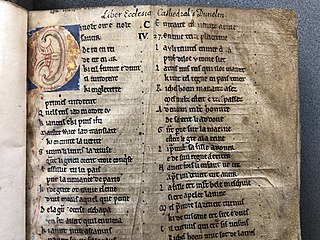

The Brut or Roman de Brut by the poet Wace is a loose and expanded translation in almost 15,000 lines of Norman-French verse of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Latin History of the Kings of Britain. It was formerly known as the Brut d'Engleterre or Roman des Rois d'Angleterre, though Wace's own name for it was the Geste des Bretons, or Deeds of the Britons. Its genre is equivocal, being more than a chronicle but not quite a fully-fledged romance.

King Arthur's family grew throughout the centuries with King Arthur's legend. Many of the legendary members of this mythical king's family became leading characters of mythical tales in their own right.

Brut y Brenhinedd is a collection of variant Middle Welsh versions of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Latin Historia Regum Britanniae. About 60 versions survive, with the earliest dating to the mid-13th century. Adaptations of Geoffrey's Historia were extremely popular throughout Western Europe during the Middle Ages, but the Brut proved especially influential in medieval Wales, where it was largely regarded as an accurate account of the early history of the Celtic Britons.

Carnwennan was the dagger of King Arthur in the Welsh Arthurian legends.

Edern ap Nudd was a knight of the Round Table in Arthur's court in early Arthurian tradition. As the son of Nudd, he is the brother of Gwyn, Creiddylad, and Owain ap Nudd. In French romances, he is sometimes made the king of a separate realm. As St Edern, he has two churches dedicated to him in Wales.

Prydwen plays a part in the early Welsh poem Preiddeu Annwfn as King Arthur's ship, which bears him to the Celtic otherworld Annwn, while in Culhwch and Olwen he sails in it on expeditions to Ireland. The 12th-century chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth named Arthur's shield after it. In the early modern period Welsh folklore preferred to give Arthur's ship the name Gwennan. Prydwen has however made a return during the last century in several Arthurian works of fiction.

Rhongomyniad, or Rhongomiant, was the spear of King Arthur in the Welsh Arthurian legends. Unlike Arthur’s two other weapons, his sword Caledfwlch and his dagger Carnwennan, Rhongomyniad has no apparent magical powers.

References

- ↑ Geoffrey of Monmouth (2007). Reeve, Michael D. (ed.). The History of the Kings of Britain: An Edition and Translation of De Gestis Britonum [Historia Regum Britanniae]. Arthurian Studies LXIX. Translated by Wright, Neil. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 198–199. ISBN 9781843834410 . Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ Parry, John J.; Caldwell, Robert A. (1959). "Geoffrey of Monmouth". In Loomis, Roger Sherman (ed.). Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages: A Collaborative History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 84. ISBN 0198115881 . Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ Lacy, Norris J.; Ashe, Geoffrey; Mancoff, Debra N. (1997). The Arthurian Handbook (2nd ed.). New York: Garland. p. 345. ISBN 9780815320814 . Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ Tatlock, J. S. P. (1950). The Legendary History of Britain: Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae and Its Early Vernacular Versions. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 202. ISBN 9780877521686 . Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ Curley 1994, p. 79.

- ↑ Ford, Patrick K. (1983). "On the Significance of Some Arthurian Names in Welsh". Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies. 30: 270. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ Curley 1994, p. 80.

- ↑ Higham, N. J. (2002). King Arthur: Myth-Making and History. London: Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 0415213053 . Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ Brault, Gerard J. (1997) [1972]. Early Blazon: Heraldic Terminology in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries with Special Reference to Arthurian Heraldry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780851157115 . Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ Arnold, I. D. O.; Pelan, M. M., eds. (1962). La partie arthurienne du Roman de Brut. Bibliothèque française et romane. Série B: Textes et documents, 1. Paris: C. Klincksieck. p. 63. ISBN 2252001305 . Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 Morris 1982, p. 127.

- ↑ Warren, Michelle R. (2000). History on the Edge: Excalibur and the Borders of Britain, 1100–1300. Medieval Cultures, Volume 22. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 162. ISBN 0816634920 . Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ Brook, G. L.; Leslie, R. F., eds. (n.d.). Lines 10501 through 10600. University of Michigan Library. Lines 10554–10557. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Lawman 1992, p. 270.

- ↑ Brook, G. L.; Leslie, R. F., eds. (n.d.). Lines 11801 through 11900. University of Michigan Library. Lines 11866–11867. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Lawman 1992, pp. 304, 447.

- ↑ Wright, William Aldis, ed. (2012) [1887]. The Metrical Chronicle of Robert of Gloucester. Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 254. ISBN 9781108052375 . Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ "Gloucester, Robert of". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23736.(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Fletcher, Robert Huntington (1965) [1906]. The Arthurian Material in the Chronicles, Especially Those of Great Britain and France. New York: Haskell House. p. 34. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ Gerald of Wales (1978). The Journey Through Wales and The Description of Wales. Translated by Thorpe, Lewis. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 281. ISBN 9780141915555 . Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ Davies, J. D. (1877). A History of West Gower, Glamorganshire. Part I. Swansea: H. W. Williams. p. 14. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History, Comprising the History of England from the Descent of the Saxons to A.D. 1237, Formerly Ascribed to Matthew Paris. Vol. 1. Translated by Giles, J. A. London: Henry G. Bohn. 1849. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ Luard, Henry Richards, ed. (2012) [1890]. Flores Historiarum. Volume 1: The Creation to A.D. 1066. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 260. ISBN 9781139382960 . Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Translated by Wayne, Thomas. New York: Algora. 2020. p. 24. ISBN 9781628944105 . Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ Vantuono, William, ed. (1984). The Pearl Poems: An Omnibus Edition. Vol. 2. New York: Garland. pp. 82, 274. ISBN 9780824054519 . Retrieved 4 October 2020.