Pandrasus is the fictional king of Greece and father of Innogen in Geoffrey of Monmouth's pseudo-history Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136).

Pandrasus is the fictional king of Greece and father of Innogen in Geoffrey of Monmouth's pseudo-history Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136).

In the Historia Regum Britanniae , Pandrasus is king of the Greeks, and has enslaved the Trojan descendants of Helenus (who had been captured by Pyrrhus as punishment for the death of his father Achilles in the Trojan War). After being exiled from Italy, Brutus of Troy arrives in Greece, discovers these Trojans, and rises to become their leader. [1]

Assaracus – a Greek noble who owns three castles, and is of Trojan descent through his mother's side – sides with the Trojans after Pandrasus allows Assaracus' fully Greek half brother to take these castles. [2] [3] Brutus agrees to support Assaracus, gathers all the Trojans and fortifies Assaracus' towns, then retreats with Assaracus and the Trojans to the woods and hills. Brutus sends a letter to Pandrasus, requesting that the Trojans be freed and allowed either to remain living in the woods, or to depart from Greece. [1]

Pandrasus consults with his nobles, then gathers an army to march on the town of Sparatinum where he suspects Brutus to be. Brutus ambushes them on their way to Sparatinum with three thousand men, and slaughters the Greeks as they try to fall back to the far side of the river Akalon (possibly the Achelous or Acheron [1] ). Pandrasus' brother Antigonus attempts to rally the Greeks, but ends up being captured along with his companion Anacletus. Brutus reinforces the town with six hundred men then retreats to the woods, while Pandrasus reassembles the Greek forces and then lays siege to the town. [1]

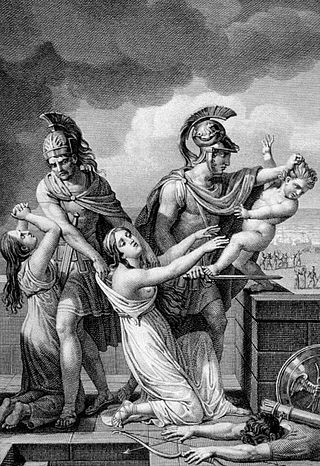

While the Greeks are encamped around Sparatinum, Brutus forces Anacletus to trick the night sentries into leaving their posts to help Antigonus, and then attacks the sleeping Greeks, massacring nearly all of them, except Pandrasus, who is kept alive. The Trojans hold a council, and decide that they have to demand their freedom to leave Greece, with plentiful resources to do so, as Pandrasus would regain his strength and have them all killed if they remained. Pandrasus is then brought in, and threatened with a cruel death if he does not agree to this, in addition to giving Brutus the hand of his eldest daughter Innogen in marriage. Pandrasus complies, offering to remain a hostage until they leave, and says that he was glad his daughter was to be married to such a great leader as Brutus. [1] [4]

Pandrasus is one of several characters that appear to have been invented by Geoffrey for the Historia. Academic Jacob Hammer suggests that he may have had in mind one of the two characters named Pandarus from Virgil's Aeneid (29–19 BCE). [5] One manuscript of the Dares Phrygius (c. fifth century CE) even spells the name Pandarus as "Pandrasus". [6]

Peter Roberts suggests that as other stories state that Pyrrhus took Helenus to Epirus, Pandrasus should therefore be considered according to this story to be king of Epirus, which would tally with the river Akalon mentioned in the story being the Acheron. He continues by noting that as the events of Pandrasus are said to have taken place about eighty years after the Trojan War, it also matches the timeframe of other accounts of the expulsion of the Achaeans from the Peloponnese around this time, which could have led them to build the "Spartan Castle" (Sparatinum) mentioned in the Historia, possibly around Pandosia. [7]

Geoffrey reused the name Pandrasus later in the Historia as the name of the king of Egypt at the time of King Arthur. [5] [8]

John of Hauville's Architrenius (c. 1184) describes the marriage of Innogen and Brutus, saying they "joined the royal house of Anchises to that of Greece. Pandrasus extended the royal line in one direction, Silvius in another, and the star derived from this union of stars poured forth the fuller radiance of a triple light." [9]

Scholars from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century who studied Eustache Deschamps' ballad in praise of Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1380 on) interpreted a difficult line of the poem "aux ignorans de la langue pandra" as meaning "for those ignorant of the tongue of Pandrasus". Later scholarship suggested that "a Pandarus for those ignorant of the language" was more likely, referring to Pandarus from Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde (c. 1380s). [10]

Alfred of Beverley was an English chronicler, and sacrist of the collegiate church of St John the Evangelist and St John of Beverley wrote a history of Britain and England in nine chapters from its supposed foundation by the Trojan Brutus, down to the death of Henry I in 1135. Alfred's chief sources, in addition to Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica de Gentis Anglorum, are Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, Henry of Huntingdon's Historia Anglorum, The Chronicle of John of Worcester, and the Historia Regum, attributed to Symeon of Durham.

Geoffrey of Monmouth was a Catholic cleric from Monmouth, Wales, and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography and the popularity of tales of King Arthur. He is best known for his chronicle The History of the Kings of Britain which was widely popular in its day, being translated into other languages from its original Latin. It was given historical credence well into the 16th century, but is now considered historically unreliable.

In Greek mythology, Helenus was a gentle and clever seer. He was also a Trojan prince as the son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy, and the twin brother of the prophetess Cassandra. He was also called Scamandrios, and was a lover of Apollo.

In Greek mythology, Neoptolemus, originally called Pyrrhus at birth, was the son of the warrior Achilles and the princess Deidamia, and the brother of Oneiros. He became the mythical progenitor of the ruling dynasty of the Molossians of ancient Epirus. In a reference to his pedigree, Neoptolemus was sometimes called Achillides or, from his grandfather's or great-grandfather's names, Pelides or Aeacides.

In Greek mythology, Astyanax was the son of Hector, the crown prince of Troy, and his wife, Princess Andromache of Cilician Thebe. His birth name was Scamandrius, but the people of Troy nicknamed him Astyanax, because he was the son of the city's great defender and the heir apparent's firstborn son.

Brutus, also called Brute of Troy, is a mythical British king. He is described as a legendary descendant of the Trojan hero Aeneas, known in medieval British legend as the eponymous founder and first king of Britain. This legend first appears in the Historia Brittonum, an anonymous 9th-century historical compilation to which commentary was added by Nennius, but is best known from the account given by the 12th-century chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae.

Corineus, in medieval British legend, was a prodigious warrior, a fighter of giants, and the eponymous founder of Cornwall.

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. The 12th-century Catholic cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, widely popular in its day, is a central component of the Matter of Britain.

Locrinus was a legendary king of the Britons, as recounted by the 12th-century chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae. He came to power in 1125BC.

Gwendolen, also known as Gwendolin, or Gwendolyn was a legendary ruler of ancient Britain. She came to power in 1115BC.

Ebraucus was a legendary king of the Britons, as recounted in Geoffrey of Monmouth's pseudohistory Historia Regum Britanniae. Later estimations from the dates given in the text place the events of this story around 1040 BC. He was the son of King Mempricius and father of Brutus Greenshield.

Historia regum Britanniae, originally called De gestis Britonum, is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It chronicles the lives of the kings of the Britons over the course of two thousand years, beginning with the Trojans founding the British nation and continuing until the Anglo-Saxons assumed control of much of Britain around the 7th century. It is one of the central pieces of the Matter of Britain.

Trinovantum is the name in medieval British legend that was given to London, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, when it was founded by the exiled Trojan Brutus, who called it Troia Nova, which was gradually corrupted to Trinovantum. The legend says that it was later rebuilt by King Lud, who named it Caer Lud after himself and that the name became corrupted to Kaer Llundain and finally London. The legend is part of the Matter of Britain.

Innogen is a character in the Historia Regum Britanniae and subsequent medieval British pseudo-history. She was said to have been a Greek princess, the daughter of King Pandrasus, and to have become Britain's first Queen consort as the wife of Brutus of Troy, the purported first king of Britain who was said to have lived around the 12th century BC. Her sons Locrinus, Camber, and Albanactus went on to rule Loegria, Cambria, and Alba respectively.

Alba Silvius was in Roman mythology the fifth king of Alba Longa. He was the son of Latinus Silvius and the father of Atys. He reigned thirty-nine years.

Brut y Brenhinedd is a collection of variant Middle Welsh versions of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Latin Historia Regum Britanniae. About 60 versions survive, with the earliest dating to the mid-13th century. Adaptations of Geoffrey's Historia were extremely popular throughout Western Europe during the Middle Ages, but the Brut proved especially influential in medieval Wales, where it was largely regarded as an accurate account of the early history of the Celtic Britons.

Walter of Oxford was a cleric and writer. He served as archdeacon of Oxford in the 12th century. Walter was a friend of Geoffrey of Monmouth, who claimed he got his chief source for the Historia Regum Britanniae from him.

Goffar known as Goffar the Pict, was a pseudo-historical king of Aquitaine around the year 1000 BCE in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae. In the story, he was defeated by Brutus of Troy and Corineus on their way to Britain. Later histories of Britain and France included Goffar from Historia Regum Britanniae, and sometimes expanded the story with additional details.

Gogmagog was a legendary giant in Welsh and later English mythology. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, he was a giant inhabitant of Albion, thrown off a cliff during a wrestling match with Corineus. Gogmagog was the last of the Giants found by Brutus and his men inhabiting the land of Albion.