The gens Furia, originally written Fusia, and sometimes found as Fouria on coins, was one of the most ancient and noble patrician houses at Rome. Its members held the highest offices of the state throughout the period of the Roman Republic. The first of the Furii to attain the consulship was Sextus Furius in 488 BC.

The gens Aurelia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome, which flourished from the third century BC to the latest period of the Empire. The first of the Aurelian gens to obtain the consulship was Gaius Aurelius Cotta in 252 BC. From then to the end of the Republic, the Aurelii supplied many distinguished statesmen, before entering a period of relative obscurity under the early emperors. In the latter part of the first century, a family of the Aurelii rose to prominence, obtaining patrician status, and eventually the throne itself. A series of emperors belonged to this family, through birth or adoption, including Marcus Aurelius and the members of the Severan dynasty.

The gens Junia or Iunia was one of the most celebrated families of ancient Rome. The gens may originally have been patrician, and was already prominent in the last days of the Roman monarchy. Lucius Junius Brutus was the nephew of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the seventh and last king of Rome, and on the expulsion of Tarquin in 509 BC, he became one of the first consuls of the Roman Republic.

The gens Papiria was a patrician family at ancient Rome. According to tradition, the Papirii had already achieved prominence in the time of the kings, and the first Rex Sacrorum and Pontifex Maximus of the Republic were members of this gens. Lucius Papirius Mugillanus was the first of the Papirii to obtain the consulship in 444 BC. The patrician members of the family regularly occupied the highest offices of the Roman state down to the time of the Punic Wars. Their most famous member was Lucius Papirius Cursor, five times consul between 326 and 313 BC, who earned three triumphs during the Samnite Wars. Most of the Papirii who held office under the later Republic belonged to various plebeian branches of the family. Although the most illustrious Papirii flourished in the time of the Republic, a number of the family continued to hold high office during the first two centuries of the Empire.

The gens Quinctia, sometimes written Quintia, was a patrician family at ancient Rome. Throughout the history of the Republic, its members often held the highest offices of the state, and it produced some men of importance even during the imperial period. For the first forty years after the expulsion of the kings the Quinctii are not mentioned, and the first of the gens who obtained the consulship was Titus Quinctius Capitolinus Barbatus in 471 BC; but from that year their name constantly appears in the Fasti consulares.

Titus Manlius Torquatus was a politician of the Roman Republic. He had a long and distinguished career, being consul in 235 BC and 224 BC, censor in 231 BC, and dictator in 208 BC. He was an ally of Fabius Maximus "Cunctator".

The gens Cornelia was one of the greatest patrician houses at ancient Rome. For more than seven hundred years, from the early decades of the Republic to the third century AD, the Cornelii produced more eminent statesmen and generals than any other gens. At least seventy-five consuls under the Republic were members of this family, beginning with Servius Cornelius Maluginensis in 485 BC. Together with the Aemilii, Claudii, Fabii, Manlii, and Valerii, the Cornelii were almost certainly numbered among the gentes maiores, the most important and powerful families of Rome, who for centuries dominated the Republican magistracies. All of the major branches of the Cornelian gens were patrician, but there were also plebeian Cornelii, at least some of whom were descended from freedmen.

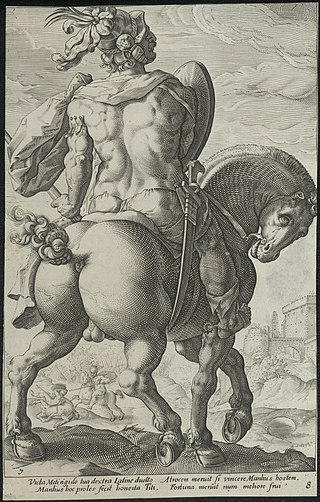

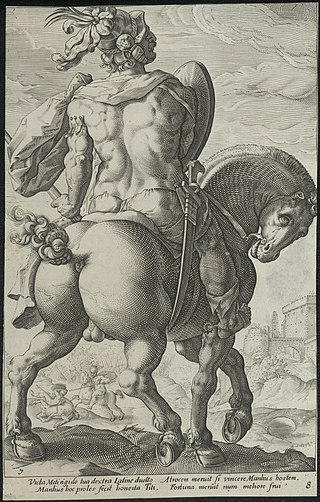

Titus Manlius Imperiosus Torquatus was a famous politician and general of the Roman Republic, of the old gens Manlia. He had an outstanding career, being consul three times, in 347, 344, and 340 BC, and dictator three times, in 353, 349, and 320 BC. He was one of the early heroes of the Republic, alongside Cincinnatus, Cornelius Cossus, Furius Camillus, and Valerius Corvus. As a young military tribune, he defeated a huge Gaul in one of the most famous duels of the Republic, which earned him the epithet Torquatus after the torc he took from the Gaul's body. He was also known for his moral virtues, and his severity became famous after he had his own son executed for disobeying orders in a battle. His life was seen as a model for his descendants, who tried to emulate his heroic deeds, even centuries after his death.

The gens Sempronia was one of the most ancient and noble houses of ancient Rome. Although the oldest branch of this gens was patrician, with Aulus Sempronius Atratinus obtaining the consulship in 497 BC, the thirteenth year of the Republic, but from the time of the Samnite Wars onward, most if not all of the Sempronii appearing in history were plebeians. Although the Sempronii were illustrious under the Republic, few of them attained any importance or notice in imperial times.

Gnaeus Manlius Vulso was Roman consul in 474 BC with Lucius Furius Medullinus Fusus.

The gens Pomponia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Its members appear throughout the history of the Roman Republic, and into imperial times. The first of the gens to achieve prominence was Marcus Pomponius, tribune of the plebs in 449 BC; the first who obtained the consulship was Manius Pomponius Matho in 233 BC.

The gens Plaetoria was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. A number of Plaetorii appear in history during the first and second centuries BC, but none of this gens ever obtained the consulship. Several Plaetorii issued denarii from the late 70s into the 40s, of which one of the best known alludes to the assassination of Caesar on the Ides of March, since one of the Plaetorii was a partisan of Pompeius during the Civil War.

Vopiscus Julius Iullus was a Roman statesman, who held the consulship in 473 BC, a year in which the authority of the Roman magistrates was threatened after the murder of a tribune of the plebs.

The gens Manilia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Members of this gens are frequently confused with the Manlii, Mallii, and Mamilii. Several of the Manilii were distinguished in the service of the Republic, with Manius Manilius obtaining the consulship in 149 BC; but the family itself remained small and relatively unimportant.

Aulus Manlius Vulso was a Roman politician in the 5th century BC, and was a member of the first college of the decemviri in 451 BC. In 474 BC, he may have been elected consul with Lucius Furius Medullinus. Whether or not the decemvir is the same man as the consul of 474 BC remains unknown.

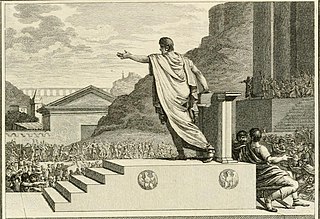

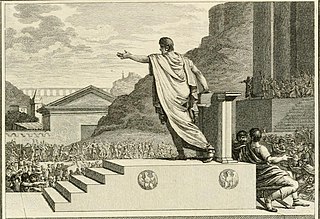

Titus Manlius Torquatus was a politician of the Roman Republic, who became consul in 165 BC. Born into a prominent family, he sought to emulate the legendary severity of his ancestors, notably by forcing his son to commit suicide after he had been accused of corruption. Titus had a long career and was a respected jurist. He was also active in diplomatic affairs; he notably served as ambassador to Egypt in 162 BC in a mission to support the claims of Ptolemy VIII Physcon over Cyprus.

Aulus Manlius Torquatus Atticus was a politician during the Roman Republic. Born into the prominent patrician family of the Manlii Torquati, he had a distinguished career, becoming censor in 247 BC, then twice consul in 244 and 241 BC, and possibly princeps senatus in 220 BC. Despite these prestigious magistracies, little is known about his life. He was a commander who served during the First Punic War, and might have pushed for the continuation of the war even after Carthage had sued for peace following the Roman victory at the Aegate Islands in 241 BC. The same year, he suppressed the revolt of the Faliscans in central Italy, for which he was awarded a triumph. At this occasion, he may have introduced the cult of Juno Curitis at Rome.

Titus Quinctius PoenusCincinnatus was a consul of the Roman Republic in 431 and 428 BC and a consular tribune in 426 BC. He might have been consular tribune again in 420 BC.

Aulus Manlius Vulso Capitolinus was a consular tribune of the Roman Republic in 405, 402 and 397 BC.

Aulus Cornelius Cossus Arvina was a Roman statesman and general who served as both consul and Magister Equitum twice, and Dictator in 322 BC.