The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member of the clan. The family established dynastic, hereditary rule with Mu'awiya I, the long-time governor of Greater Syria, who became caliph after the end of the First Fitna in 661. After Mu'awiya's death in 680, conflicts over the succession resulted in the Second Fitna, and power eventually fell to Marwan I, from another branch of the clan. Syria remained the Umayyads' main power base thereafter, with Damascus as their capital.

Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan was the seventh Umayyad caliph, ruling from 715 until his death. He was the son of Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685–705) and Wallada bint al-Abbas. He began his career as governor of Palestine, while his father Abd al-Malik and brother al-Walid I reigned as caliphs. There, the theologian Raja ibn Haywa al-Kindi mentored him, and he forged close ties with Yazid ibn al-Muhallab, a major opponent of al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, al-Walid's powerful viceroy of Iraq and the eastern Caliphate. Sulayman resented al-Hajjaj's influence over his brother. As governor, Sulayman founded the city of Ramla and built the White Mosque in it. The new city superseded Lydda as the district capital of Palestine. Lydda was at least partly destroyed and its inhabitants may have been forcibly relocated to Ramla, which developed into an economic hub, became home to many Muslim scholars, and remained the commercial and administrative center of Palestine until the 11th century.

Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz ibn Marwan was the eighth Umayyad caliph, ruling from 717 until his death in 720. He is credited to have instituted significant reforms to the Umayyad central government, by making it much more efficient and egalitarian. His rulership is marked by the first official collection of hadiths and the mandated universal education to the populace.

Yazid ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, commonly known as Yazid II, was the ninth Umayyad caliph, ruling from 720 until his death in 724. Although he lacked administrative or military experience, he derived prestige from his lineage, being a descendant of both ruling branches of the Umayyad dynasty, the Sufyanids who founded the Umayyad Caliphate in 661 and the Marwanids who succeeded them in 684. He was designated by his half-brother, Caliph Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik, as second-in-line to the succession after their cousin Umar, as a compromise with the sons of Abd al-Malik.

Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan was the tenth Umayyad caliph, ruling from 724 until his death in 743.

Al-Walid ibn Yazid ibn Abd al-Malik, commonly known as al-Walid II, was the eleventh Umayyad caliph, ruling from 743 until his assassination in 744. He succeeded his uncle, Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik.

Abu Uqba al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah al-Hakami was an Arab nobleman and general of the Hakami tribe. During the course of the early 8th century, he was at various times governor of Basra, Sistan and Khurasan, Armenia and Adharbayjan. A legendary warrior already during his lifetime, he is best known for his campaigns against the Khazars on the Caucasus front, culminating in his death in the Battle of Marj Ardabil in 730.

The Battle of Akroinon was fought at Akroinon or Akroinos in Phrygia, on the western edge of the Anatolian plateau, in 740 between an Umayyad Arab army and the Byzantine forces. The Arabs had been conducting regular raids into Anatolia for the past century, and the 740 expedition was the largest in recent decades, consisting of three separate divisions. One division, 20,000 strong under Abdallah al-Battal and al-Malik ibn Shu'aib, was confronted at Akroinon by the Byzantines under the command of Emperor Leo III the Isaurian and his son, the future Constantine V. The battle resulted in a decisive Byzantine victory. Coupled with the Umayyad Caliphate's troubles on other fronts and the internal instability before and after the Abbasid Revolt, this put an end to major Arab incursions into Anatolia for three decades.

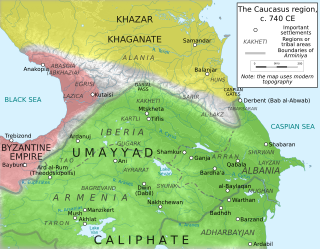

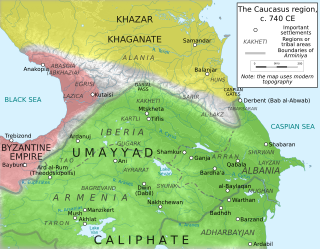

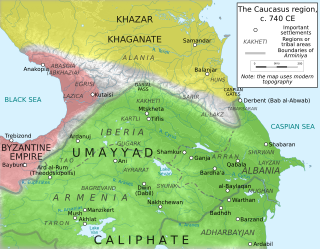

The Arab–Khazar wars were a series of conflicts fought between the Khazar Khaganate and successive Arab caliphates in the Caucasus region from c. 642 to 799 CE. Smaller native principalities were also involved in the conflict as vassals of the two empires. Historians usually distinguish two major periods of conflict, the First Arab–Khazar War and Second Arab–Khazar War ; the wars also involved sporadic raids and isolated clashes from the mid-seventh century to the end of the eighth century.

Arminiya, also known as the Ostikanate of Arminiya or the Emirate of Armenia, was a political and geographic designation given by the Muslim Arabs to the lands of Greater Armenia, Caucasian Iberia, and Caucasian Albania, following their conquest of these regions in the 7th century. Though the caliphs initially permitted an Armenian prince to represent the province of Arminiya in exchange for tribute and the Armenians' loyalty during times of war, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan introduced direct Arab rule of the region, headed by an ostikan with his capital in Dvin. According to the historian Stephen H. Rapp in the third edition of the Encyclopaedia of Islam:

Early Arabs followed Sāsānian, Parthian Arsacid, and ultimately Achaemenid practice by organising most of southern Caucasia into a large regional zone called Armīniya.

Jund Dimashq was the largest of the sub-provinces, into which Syria was divided under the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties. It was named after its capital and largest city, Damascus ("Dimashq"), which in the Umayyad period was also the capital of the Caliphate.

Mu'awiya ibn Hisham (Arabic: معاوية بن هشام, romanized: Muʿāwiya ibn Hishām; was an Arab general and prince, the son of the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, who distinguished himself in the Arab–Byzantine Wars. His son, Abd al-Rahman ibn Mu'awiya, was the founder of the Emirate of Córdoba and the Umayyad line of al-Andalus.

al-ʿAbbās ibn al-Walīd ibn ʿAbd al-Malik was an Umayyad prince and general, the eldest son of Caliph al-Walid I. He distinguished himself as a military leader in the Byzantine–Arab Wars of the early 8th century, especially in the Siege of Tyana in 707–708, and was often a partner of his uncle Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik during these campaigns. He or his father are credited for founding the short-lived city of Anjar in modern Lebanon.

Umar ibn Hubayra al-Fazari was a prominent Umayyad general and governor of Iraq, who played an important role in the Qays–Yaman conflict of this period.

Sa'id ibn Amr al-Harashi was a prominent Arab general and governor of the Umayyad Caliphate, who played an important role in the Arab–Khazar wars.

Sa'id ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, also known as Saʿīd al-Khayr, was an Umayyad prince and governor.

Maslama ibn Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, also known by his kunyaAbu Shakir, was an Umayyad prince and commander.

Al-Jazira, also known as Jazirat Aqur or Iqlim Aqur, was a province of the Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, spanning at minimum most of Upper Mesopotamia, divided between the districts of Diyar Bakr, Diyar Rabi'a and Diyar Mudar, and at times including Mosul, Arminiya and Adharbayjan as sub-provinces. Following its conquest by the Muslim Arabs in 639/40, it became an administrative unit attached to the larger district of Jund Hims. It was separated from Hims during the reigns of caliphs Mu'awiya I or Yazid I and came under the jurisdiction of Jund Qinnasrin. It was made its own province in 692 by Caliph Abd al-Malik. After 702, it frequently came to span the key districts of Arminiya and Adharbayjan along the Caliphate's northern frontier, making it a super-province. The predominance of Arabs from the Qays/Mudar and Rabi'a groups made it a major recruitment pool of tribesmen for the Umayyad armies and the troops of the Jazira played a key military role under the Umayyad caliphs in the 8th century, peaking under the last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II, until the toppling of the Umayyads by the Abbasids in 750.

Saʿīd ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Malik was an Umayyad prince and commander who participated in the Arab–Byzantine wars and the Third Muslim Civil War, often in association with his brother, Sulayman ibn Hisham. For revolting against Caliph Marwan II, he was imprisoned in 746, and he died trying to escape.