The Declaration of Independence, formally titled The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, is the founding document of the United States. On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress, who had convened at the Pennsylvania State House, later renamed Independence Hall, in the colonial era capital of Philadelphia. The declaration explains to the world why the Thirteen Colonies regarded themselves as independent sovereign states no longer subject to British colonial rule.

Mecklenburg County is a county located in the southwestern region of the state of North Carolina, in the United States. At the 2020 census, the population was 1,115,482. In 2022, the population was estimated to be 1,145,392, making it the second-most populous county in North Carolina and the first county in the Carolinas to surpass one million in population. Its county seat is Charlotte, the state's largest community.

Joseph Hewes was an American Founding Father and a signer of the Continental Association and U.S. Declaration of Independence. Hewes was a native of Princeton, New Jersey, where he was born in 1730. His parents were members of the Society of Friends, commonly known as Quakers. Early biographies of Hewes falsely claim that his parents came from Connecticut. Hewes may have attended the College of New Jersey, known today as Princeton University but there is no record of his attendance. He did, in all probability, attend the grammar school set up by the Stonybrook Quaker Meeting near Princeton.

The flag of the state of North Carolina, often referred to as the North Carolina flag, N.C. flag, or North Star, is the state flag of the U.S. state of North Carolina.

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence is a text published in 1819 with the now disputed claim that it was the first declaration of independence made in the Thirteen Colonies during the American Revolution. It was supposedly signed on May 20, 1775, in Charlotte, North Carolina, by a committee of citizens of Mecklenburg County, who declared independence from Great Britain after hearing of the battle of Concord. If true, the Mecklenburg Declaration preceded the United States Declaration of Independence by more than a year.

The Second Continental Congress was the late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and its associated Revolutionary War, which established American independence from the British Empire. The Congress constituted a new federation that it first named the United Colonies, and in 1776, renamed the United States of America. The Congress began convening in Philadelphia, on May 10, 1775, with representatives from 12 of the 13 colonies, after the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

Tryon County is a former county which was located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. It was formed in 1768 from the part of Mecklenburg County west of the Catawba River, although the legislative act that created it did not become effective until April 10, 1769. Due to inaccurate and delayed surveying, Tryon County encompassed a large area of northwestern South Carolina. It was named for William Tryon, governor of the North Carolina Colony from 1765 to 1771.

The Suffolk Resolves was a declaration made on September 9, 1774, by the leaders of Suffolk County, Massachusetts. The declaration rejected the Massachusetts Government Act and resulted in a boycott of imported goods from Britain unless the Intolerable Acts were repealed. The Resolves were recognized by statesman Edmund Burke as a major development in colonial animosity leading to adoption of the United States Declaration of Independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1776, and he urged British conciliation with the American colonies, to little effect. The First Continental Congress endorsed the Resolves on September 17, 1774, and passed the similarly themed Continental Association on October 20, 1774.

What is known today as the Tryon Resolves was a brief declaration adopted and signed by "subscribers" to the Tryon County Association that was formed in Tryon County, North Carolina in the early days of the American Revolution. In the Resolves—a modern name for the Association's charter document—the county representatives vowed resistance to the increasingly coercive actions being enacted by the government of Great Britain against its North American colonies. The document was signed on August 14, 1775, but—like other similar declarations of the time—stopped short of calling for total independence from Britain.

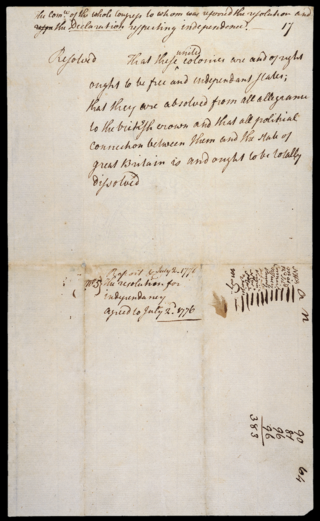

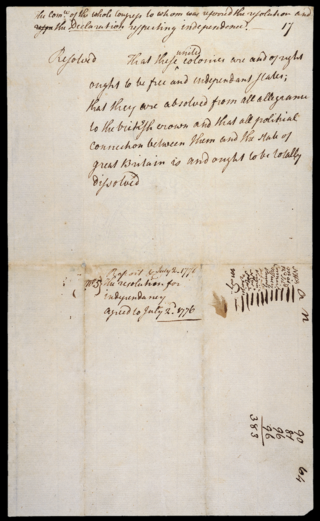

The Lee Resolution, also known as "The Resolution for Independence", was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2, 1776, which resolved that the Thirteen Colonies, then referred to as the United Colonies, were "free and independent States" and separate from the British Empire, which created what became the United States of America. News of this act was published that evening in The Pennsylvania Evening Post and the next day in The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Declaration of Independence, which officially announced and explained the case for independence, was approved two days later, on July 4, 1776.

Alexander Craighead (1705–1766) was a Scots-Irish American preacher.

Pennsylvania was the site of many key events associated with the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War. The city of Philadelphia, then capital of the Thirteen Colonies and the largest city in the colonies, was a gathering place for the Founding Fathers who discussed, debated, developed, and ultimately implemented many of the acts, including signing the Declaration of Independence, that inspired and launched the revolution and the quest for independence from the British Empire.

The United Colonies was the name used by the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia to describe the proto-states comprising the Thirteen Colonies in 1775 and 1776, before and as independence was declared. Continental currency banknotes displayed the name 'The United Colonies' from May 1775 until February 1777, and the name was being used as a colloquial phrase to refer to the colonies as a whole before the Second Congress met, although the precise place or date of its origin is unknown.

The Liberty Point Resolves, also known as "The Cumberland Association", was a resolution signed by fifty residents of Cumberland County, North Carolina, early in the American Revolution.

Prior to the American Revolution, the colonies formed Committees of Safety to represent the interests of their respective communities. They determined the judicial outcome of civil cases, organized the local militia, arrested and tried those suspected of criminal or subversive activities.

The Bush Declaration, also known as the Bush River Declaration, the Bush River Resolution, and the Harford Declaration, was a resolution adopted on March 22, 1775, in Harford County, Maryland. Like other similar resolutions in the Thirteen Colonies around this time, the Bush Declaration expressed support for the Patriot cause in the emerging American Revolution.

Abraham Alexander was a public figure in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, during the American Revolution. He chaired the meetings that produced the radical Mecklenburg Resolves and, allegedly, the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence.

Colonel Robert Irwin (1738-1800) of Steele Creek Township, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina was a long term North Carolina State Senator. The first state senator ever elected from Mecklenburg County, he served as the North Carolina senator from Mecklenburg County in the years 1778-1783, and again, in the years 1787 and 1795, and, finally, from 1797 to 1800, dying in office.

The Augusta Declaration, or the Memorial of Augusta County Committee, May 10, 1776, was a statement presented to the Fifth Virginia Convention in Williamsburg, Virginia on May 10, 1776. The Declaration announced the necessity of the Thirteen Colonies to form a permanent and independent union of states and national government separate from Great Britain, with whom the Colonies were at war.

The Seal of Charlotte was first established during the tenure of mayor Charles A. Bland, and was designed over a period stretching from 1911 to 1915. It was adopted on the city's first flag in 1929, which still remains in use today. This seal itself was rescinded at an unknown date and replaced with the present one. It is used to authorize executive documents from the city, including, but not limited to, mayoral proclamations and resolutions from the city council.