Social norms are shared standards of acceptable behavior by groups. Social norms can both be informal understandings that govern the behavior of members of a society, as well as be codified into rules and laws. Social normative influences or social norms, are deemed to be powerful drivers of human behavioural changes and well organized and incorporated by major theories which explain human behaviour. Institutions are composed of multiple norms. Norms are shared social beliefs about behavior; thus, they are distinct from "ideas", "attitudes", and "values", which can be held privately, and which do not necessarily concern behavior. Norms are contingent on context, social group, and historical circumstances.

Social control is a concept within the disciplines of the social sciences. One dictionary defines social control in terms of a certain set of rules and standards in society that keep individuals bound to conventional standards as well as to the use of formalized mechanisms. In sociology, Foucault's disciplinary model preceded the social-control model.

A moral panic is a widespread feeling of fear, often an irrational one, that some evil person or thing threatens the values, interests, or well-being of a community or society. It is "the process of arousing social concern over an issue", usually perpetuated by moral entrepreneurs and mass media coverage, and exacerbated by politicians and lawmakers. Moral panic can give rise to new laws aimed at controlling the community.

In criminology, corporate crime refers to crimes committed either by a corporation, or by individuals acting on behalf of a corporation or other business entity. For the worst corporate crimes, corporations may face judicial dissolution, sometimes called the "corporate death penalty", which is a legal procedure in which a corporation is forced to dissolve or cease to exist.

The deviancy amplification spiral and deviancy amplification are terms used by interactionist sociologists to refer to the way levels of deviance or crime can be increased by the societal reaction to deviance itself.

Role theory is a concept in sociology and in social psychology that considers most of everyday activity to be the acting-out of socially defined categories. Each role is a set of rights, duties, expectations, norms, and behaviors that a person has to face and fulfill. The model is based on the observation that people behave in a predictable way, and that an individual's behavior is context specific, based on social position and other factors. Research conducted on role theory mainly centers around the concepts of consensus, role conflict, role taking, and conformity. The theatre is a metaphor often used to describe role theory.

Abnormality is a behavioral characteristic assigned to those with conditions that are regarded as rare or dysfunctional. Behavior is considered to be abnormal when it is atypical or out of the ordinary, consists of undesirable behavior, and results in impairment in the individual's functioning. Abnormality in behavior, is that in which is considered deviant from specific societal, cultural and ethical expectations. These expectations are broadly dependent on age, gender, traditional and societal categorizations. The definition of abnormal behavior is an often debated issue in abnormal psychology, because of these subjective variables.

Medicalization is the process by which human conditions and problems come to be defined and treated as medical conditions, and thus become the subject of medical study, diagnosis, prevention, or treatment. Medicalization can be driven by new evidence or hypotheses about conditions; by changing social attitudes or economic considerations; or by the development of new medications or treatments.

Labeling theory posits that self-identity and the behavior of individuals may be determined or influenced by the terms used to describe or classify them. It is associated with the concepts of self-fulfilling prophecy and stereotyping. Labeling theory holds that deviance is not inherent in an act, but instead focuses on the tendency of majorities to negatively label minorities or those seen as deviant from standard cultural norms. The theory was prominent during the 1960s and 1970s, and some modified versions of the theory have developed and are still currently popular. Stigma is defined as a powerfully negative label that changes a person's self-concept and social identity.

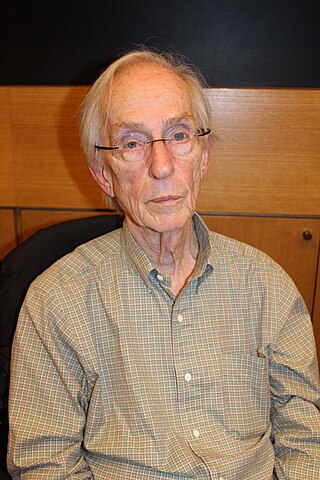

Howard Saul Becker was an American sociologist who taught at Northwestern University. Becker made contributions to the sociology of deviance, sociology of art, and sociology of music. Becker also wrote extensively on sociological writing styles and methodologies. Becker's 1963 book Outsiders provided the foundations for labeling theory. Becker was often called a symbolic interactionist or social constructionist, although he did not align himself with either method. A graduate of the University of Chicago, Becker was considered part of the second Chicago School of Sociology, which also includes Erving Goffman and Anselm Strauss.

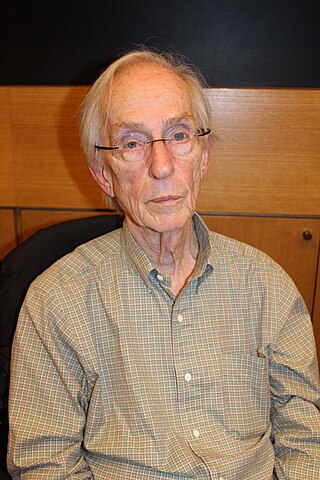

Erich Goode is an American sociologist specializing in the sociology of deviance. He has written a number of books on the field in general, as well as on specific deviant topics. He was a professor at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

From a sociological perspective, deviance is defined as the violation or drift from the accepted social norms.

Primary deviance is the initial stage in defining deviant behavior. Prominent sociologist Edwin Lemert conceptualized primary deviance as engaging in the initial act of deviance. This is very common throughout society, as everyone takes part in basic form violations. Primary deviance does not result in a person internalizing a deviant identity, so one does not alter their self-concept to include this deviant identity. It is not until the act becomes labeled or tagged, that secondary deviation may materialize. According to Lemert, primary deviance is the acts that are carried out by the individual that allows them to carry the deviant label.

A label is an abstract concept in sociology used to group people together based on perceived or held identity. Labels are a mode of identifying social groups. Labels can create a sense of community within groups, but they can also cause harm when used to separate individuals and groups from mainstream society. Individuals may choose a label, or they may be assigned one by others. The act of labeling may affect an individual's behavior and their reactions to the social world.

Marxist criminology is one of the schools of criminology. It parallels the work of the structural functionalism school which focuses on what produces stability and continuity in society but, unlike the functionalists, it adopts a predefined political philosophy. As in conflict criminology, it focuses on why things change, identifying the disruptive forces in industrialized societies, and describing how society is divided by power, wealth, prestige, and the perceptions of the world. "The shape and character of the legal system in complex societies can be understood as deriving from the conflicts inherent in the structure of these societies which are stratified economically and politically". It is concerned with the causal relationships between society and crime, i.e. to establish a critical understanding of how the immediate and structural social environment gives rise to crime and criminogenic conditions.

In criminology, social control theory proposes that exploiting the process of socialization and social learning builds self-control and reduces the inclination to indulge in behavior recognized as antisocial. It derived from functionalist theories of crime and was developed by Ivan Nye (1958), who proposed that there were three types of control:

Sociology of terrorism is a field of sociology that seeks to understand terrorism as a social phenomenon. The field defines terrorism, studies why it occurs and evaluates its impacts on society. The sociology of terrorism draws from the fields of political science, history, economics and psychology. The sociology of terrorism differs from critical terrorism studies, emphasizing the social conditions that enable terrorism. It also studies how individuals as well as states respond to such events.

Deviance or the sociology of deviance explores the actions and/or behaviors that violate social norms across formally enacted rules as well as informal violations of social norms. Although deviance may have a negative connotation, the violation of social norms is not always a negative action; positive deviation exists in some situations. Although a norm is violated, a behavior can still be classified as positive or acceptable.

A social panic is a state where a social or community group reacts negatively and in an extreme or irrational manner to unexpected or unforeseen changes in their expected social status quo. According to Folk Devils and Moral Panics by Stanley Cohen, the definition can be broken down to many different sections. The sections, which were identified by Erich Goode and Nachman Ben-Yehuda in 1994, include concern, hostility, consensus, disproportionality, and volatility. Concern, which is not to be mistaken with fear, is about the possible or potential threat. Hostility occurs when an outrage occurs toward the people who were a part of the problem and agencies who are accountable. These people are seen as the enemy since their behavior is viewed as a danger to society. Consensus includes a distributed agreement that an actual threat is going to take place. This is where the media and other sources come in to aid in spreading of the panic. Disproportionality compares people's reactions to the actual seriousness of the condition. Volatility is when there is no longer any more panic.

Criminology is the interdisciplinary study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is a multidisciplinary field in both the behavioural and social sciences, which draws primarily upon the research of sociologists, political scientists, economists, legal sociologists, psychologists, philosophers, psychiatrists, social workers, biologists, social anthropologists, scholars of law and jurisprudence, as well as the processes that define administration of justice and the criminal justice system.