Angelina Weld Grimké was an African-American journalist, teacher, playwright, and poet.

Theodore Dwight Weld was one of the architects of the American abolitionist movement during its formative years from 1830 to 1844, playing a role as writer, editor, speaker, and organizer. He is best known for his co-authorship of the authoritative compendium American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, published in 1839. Harriet Beecher Stowe partly based Uncle Tom’s Cabin on Weld's text; the latter is regarded as second only to the former in its influence on the antislavery movement. Weld remained dedicated to the abolitionist movement until slavery was ended by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865.

Angelina Emily Grimké Weld was an American abolitionist, political activist, women's rights advocate, and supporter of the women's suffrage movement. At one point she was the best known, or "most notorious," woman in the country. She and her sister Sarah Moore Grimké were considered the only notable examples of white Southern women abolitionists. The sisters lived together as adults, while Angelina was the wife of abolitionist leader Theodore Dwight Weld.

Charles Lenox Remond was an American orator, activist and abolitionist based in Massachusetts. He lectured against slavery across the Northeast, and in 1840 traveled to the British Isles on a tour with William Lloyd Garrison. During the American Civil War, he recruited blacks for the United States Colored Troops, helping staff the first two units sent from Massachusetts. From a large family of African-American entrepreneurs, he was the brother of Sarah Parker Remond, also a lecturer against slavery.

The Liberator (1831–1865) was a weekly abolitionist newspaper, printed and published in Boston by William Lloyd Garrison and, through 1839, by Isaac Knapp. Religious rather than political, it appealed to the moral conscience of its readers, urging them to demand immediate freeing of the slaves ("immediatism"). It also promoted women's rights, an issue that split the American abolitionist movement. Despite its modest circulation of 3,000, it had prominent and influential readers, including all the abolitionist leaders, among them Frederick Douglass, Beriah Green, Arthur and Lewis Tappan, and Alfred Niger. It frequently printed or reprinted letters, reports, sermons, and news stories relating to American slavery, becoming a sort of community bulletin board for the new abolitionist movement that Garrison helped foster.

Sarah Moore Grimké was an American abolitionist, widely held to be the mother of the women's suffrage movement. Born and reared in South Carolina to a prominent and wealthy planter family, she moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the 1820s and became a Quaker, as did her younger sister Angelina. The sisters began to speak on the abolitionist lecture circuit, joining a tradition of women who had been speaking in public on political issues since colonial days, including Susanna Wright, Hannah Griffitts, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Anna Dickinson. They recounted their knowledge of slavery firsthand, urged abolition, and also became activists for women's rights.

Charlotte Louise Bridges Grimké was an African-American anti-slavery activist, poet, and educator. She grew up in a prominent abolitionist family in Philadelphia. She taught school for years, including during the Civil War, to freedmen in South Carolina. Later in life, she married Francis James Grimké, a Presbyterian minister who led a major church in Washington, DC, for decades. He was a nephew of the abolitionist Grimké sisters and was active in civil rights.

The Grimké sisters, Sarah Moore Grimké (1792–1873) and Angelina Emily Grimké (1805–1879), were the first nationally known white American female advocates of abolitionism and women's rights. Both sisters were public speakers, writers, and educators.

Forest Hills Cemetery is a historic 275-acre (111.3 ha) rural cemetery, greenspace, arboretum, and sculpture garden in the Forest Hills section of Jamaica Plain, a neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. The cemetery was established in 1848 as a public municipal cemetery for Roxbury, Massachusetts, but was privatized when Roxbury was annexed to Boston in 1868.

Sarah Parker Remond was an American lecturer, activist and abolitionist campaigner.

Helen Pitts Douglass (1838–1903) was an American suffragist, known for being the second wife of Frederick Douglass. She also created the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association, which became the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

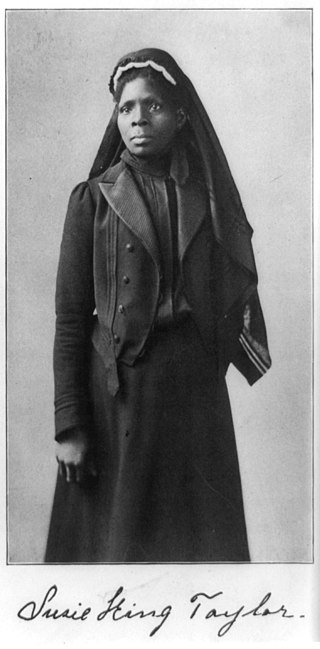

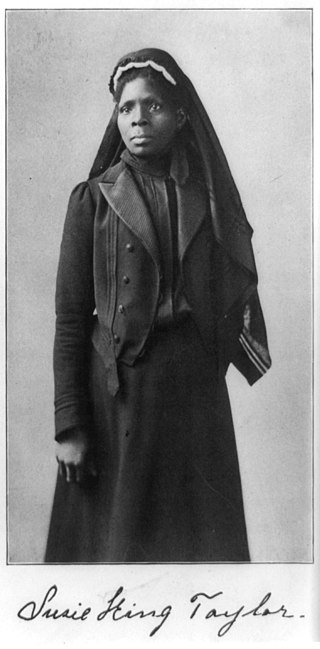

Susie King Taylor was an American nurse, educator and memoirist. Born into slavery in coastal Georgia, she is known for being the first African-American nurse during the American Civil War. Beyond her aptitude in nursing the wounded of the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment, Taylor was the first Black woman to self-publish her memoirs. She was the author of Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers (1902). She was also an educator to formerly bonded Black people in the Reconstruction-era South when she opened various Freedmen's schools for them in the city of Savannah, Georgia. Taylor was a main organizer of Corps 67 of the Woman's Relief Corps in Massachusetts (1886).

Archibald Henry Grimké was an African-American lawyer, intellectual, journalist, diplomat and community leader in the 19th and early 20th centuries. He graduated from freedmen's schools, Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and Harvard Law School, and served as American Consul to the Dominican Republic from 1894 to 1898. He was an activist for the rights of Black Americans, working in Boston and Washington, D.C. He was a national vice-president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as president of its Washington, D.C. chapter.

Leonard Chadwick was a Spanish–American War Medal of Honor recipient who served in the United States Navy as an Apprentice 1st Class aboard the USS Marblehead (C-11).

Eden Cemetery is a historic African-American cemetery located in Collingdale, Pennsylvania. It was established June 20, 1902, and is the oldest existing black owned cemetery in the United States. The cemetery covers about 53 acres and contains approximately 93,000 burials.

The Boston Women's Heritage Trail is a series of walking tours in Boston, Massachusetts, leading past sites important to Boston women's history. The tours wind through several neighborhoods, including the Back Bay and Beacon Hill, commemorating women such as Abigail Adams, Amelia Earhart, and Phillis Wheatley. The guidebook includes seven walks and introduces more than 200 Boston women.

Abrey Kamoo was an American physician who was reportedly born in Tunisia. In 1862, during the American Civil War, she was said to have served in disguise as a Union Army drummer boy until her sex was discovered, and then to have served as an army nurse for the remainder of the conflict. No official government or military records or other accounts exist to corroborate her claims, however, and it is likely that many of the more fanciful parts of her life story were fabricated later in life and included in her obituaries.

Julia O. Henson was an American social justice activist who founded organizations to support African American troops during World War I (1914–1918) and to provide opportunities for African Americans to thrive through the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She donated the building for the Harriet Tubman House in Boston in 1904.

Woodlawn Cemetery is an American rural cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts. It is the third-oldest rural cemetery in Greater Boston.