Related Research Articles

Multiplesclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease in which the insulating covers of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord are damaged. This damage disrupts the ability of parts of the nervous system to transmit signals, resulting in a range of signs and symptoms, including physical, mental, and sometimes psychiatric problems. Specific symptoms can include double vision, vision loss, eye pain, muscle weakness, and loss of sensation or coordination. MS takes several forms, with new symptoms either occurring in isolated attacks or building up over time. In the relapsing forms of MS, between attacks, symptoms may disappear completely, although some permanent neurological problems often remain, especially as the disease advances. In the progressive forms of MS, bodily function slowly deteriorates and disability worsens once symptoms manifest and will steadily continue to do so if the disease is left untreated.

Oligoclonal bands (OCBs) are bands of immunoglobulins that are seen when a patient's blood serum, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is analyzed. They are used in the diagnosis of various neurological and blood diseases. Oligoclonal bands are present in the CSF of more than 95% of patients with clinically definite multiple sclerosis.

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) are a spectrum of autoimmune diseases characterized by acute inflammation of the optic nerve and the spinal cord (myelitis). Episodes of ON and myelitis can be simultaneous or successive. A relapsing disease course is common, especially in untreated patients.

The McDonald criteria are diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS). These criteria are named after neurologist W. Ian McDonald who directed an international panel in association with the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) of America and recommended revised diagnostic criteria for MS in April 2001. These new criteria intended to replace the Poser criteria and the older Schumacher criteria. They have undergone revisions in 2005, 2010 and 2017.

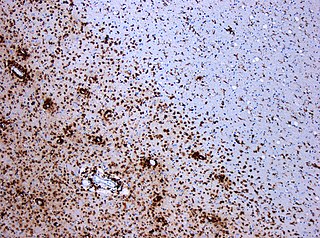

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, sometimes experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE), is an animal model of brain inflammation. It is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS). It is mostly used with rodents and is widely studied as an animal model of the human CNS demyelinating diseases, including multiple sclerosis (MS) and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). EAE is also the prototype for T-cell-mediated autoimmune disease in general.

Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS in which activated immune cells invade the central nervous system and cause inflammation, neurodegeneration, and tissue damage. The underlying cause is currently unknown. Current research in neuropathology, neuroimmunology, neurobiology, and neuroimaging, together with clinical neurology, provide support for the notion that MS is not a single disease but rather a spectrum.

Inflammatory demyelinating diseases (IDDs), sometimes called Idiopathic (IIDDs) due to the unknown etiology of some of them, are a heterogenous group of demyelinating diseases - conditions that cause damage to myelin, the protective sheath of nerve fibers - that occur against the background of an acute or chronic inflammatory process. IDDs share characteristics with and are often grouped together under Multiple Sclerosis. They are sometimes considered different diseases from Multiple Sclerosis, but considered by others to form a spectrum differing only in terms of chronicity, severity, and clinical course.

Baló's concentric sclerosis is a disease in which the white matter of the brain appears damaged in concentric layers, leaving the axis cylinder intact. It was described by József Mátyás Baló who initially named it "leuko-encephalitis periaxialis concentrica" from the previous definition, and it is currently considered one of the borderline forms of multiple sclerosis.

Research in multiple sclerosis may find new pathways to interact with the disease, improve function, curtail attacks, or limit the progression of the underlying disease. Many treatments already in clinical trials involve drugs that are used in other diseases or medications that have not been designed specifically for multiple sclerosis. There are also trials involving the combination of drugs that are already in use for multiple sclerosis. Finally, there are also many basic investigations that try to understand better the disease and in the future may help to find new treatments.

Neurofilament light polypeptide, also known as neurofilament light chain, abbreviated to NF-L or Nfl and with the HGNC name NEFL is a member of the intermediate filament protein family. This protein family consists of over 50 human proteins divided into 5 major classes, the Class I and II keratins, Class III vimentin, GFAP, desmin and the others, the Class IV neurofilaments and the Class V nuclear lamins. There are four major neurofilament subunits, NF-L, NF-M, NF-H and α-internexin. These form heteropolymers which assemble to produce 10nm neurofilaments which are only expressed in neurons where they are major structural proteins, particularly concentrated in large projection axons. Axons are particularly sensitive to mechanical and metabolic compromise and as a result axonal degeneration is a significant problem in many neurological disorders. The detection of neurofilament subunits in CSF and blood has therefore become widely used as a biomarker of ongoing axonal compromise. The NF-L protein is encoded by the NEFL gene. Neurofilament light chain is a biomarker that can be measured with immunoassays in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma and reflects axonal damage in a wide variety of neurological disorders. It is a useful marker for disease monitoring in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, and more recently Huntington's disease. It is also promising marker for follow-up of patients with brain tumors. Higher levels of blood or CSF NF-L have been associated with increased mortality, as would be expected as release of this protein reflects ongoing axonal loss. Recent work performed as a collaboration between EnCor Biotechnology Inc. and the University of Florida showed that the NF-L antibodies employed in the most widely used NF-L assays are specific for cleaved forms of NF-L generated by proteolysis induced by cell death. Methods used in different studies for NfL measurement are sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), electrochemiluminescence, and high-sensitive single molecule array (SIMOA).

Tumefactive multiple sclerosis is a condition in which the central nervous system of a person has multiple demyelinating lesions with atypical characteristics for those of standard multiple sclerosis (MS). It is called tumefactive as the lesions are "tumor-like" and they mimic tumors clinically, radiologically and sometimes pathologically.

Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is a type of brain inflammation caused by antibodies. Early symptoms may include fever, headache, and feeling tired. This is then typically followed by psychosis which presents with false beliefs (delusions) and seeing or hearing things that others do not see or hear (hallucinations). People are also often agitated or confused. Over time, seizures, decreased breathing, and blood pressure and heart rate variability typically occur. In some cases, patients may develop catatonia.

Schumacher criteria are diagnostic criteria that were previously used for identifying multiple sclerosis (MS). Multiple sclerosis, understood as a central nervous system (CNS) condition, can be difficult to diagnose since its signs and symptoms may be similar to other medical problems. Medical organizations have created diagnostic criteria to ease and standardize the diagnostic process especially in the first stages of the disease. Schumacher criteria were the first internationally recognized criteria for diagnosis, and introduced concepts still in use, as CDMS.

Current standards for diagnosing multiple sclerosis (MS) are based on the 2018 revision of McDonald criteria. They rely on MRI detection of demyelinating lesions in the CNS, which are distributed in space (DIS) and in time (DIT). It is also a requirement that any possible known disease that produces demyelinating lesions is ruled out before applying McDonald's criteria.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) can be pathologically defined as the presence of distributed glial scars (scleroses) in the central nervous system that must show dissemination in time (DIT) and in space (DIS) to be considered MS lesions.

Chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy (CRION) is a form of recurrent optic neuritis that is steroid responsive and dependent. Patients typically present with pain associated with visual loss. CRION is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion, and other demyelinating, autoimmune, and systemic causes should be ruled out. An accurate antibody test which became available commercially in 2017 has allowed most patients previously diagnosed with CRION to be re-identified as having MOG antibody disease, which is not a diagnosis of exclusion. Early recognition is crucial given risks for severe visual loss and because it is treatable with immunosuppressive treatment such as steroids or B-cell depleting therapy. Relapse that occurs after reducing or stopping steroids is a characteristic feature.

MOG antibody disease (MOGAD) or MOG antibody-associated encephalomyelitis (MOG-EM) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system. Serum anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies are present in up to half of patients with an acquired demyelinating syndrome and have been described in association with a range of phenotypic presentations, including acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, and neuromyelitis optica.

There are several ways for pharmaceuticals for treating multiple sclerosis (MS) to reach the market.

Anti-AQP4 diseases, are a group of diseases characterized by auto-antibodies against aquaporin 4.

Anne Cross is an American neurologist and neuroimmunologist and the Section Head of Neuroimmunology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri. Cross holds the Manny and Rosalyn Rosenthal–Dr. John L. Trotter Endowed Chair in Neuroimmunology at WUSTL School of Medicine and co-directs the John L Trotter Multiple Sclerosis Clinic at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. Cross is a leader in the field of neuroimmunology and was the first to discover the role of B cells in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis in animals and then in humans. Cross now develops novel imaging techniques to observe inflammation and demyelination in the central nervous systems of MS patients for diagnosis and disease management.

References

- 1 2 Hottenrott, Tilman; Dersch, Rick; Berger, Benjamin; Rauer, Sebastian; Eckenweiler, Matthias; Huzly, Daniela; Stich, Oliver (2015). "The intrathecal, polyspecific antiviral immune response in neurosarcoidosis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and autoimmune encephalitis compared to multiple sclerosis in a tertiary hospital cohort". Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 12: 27. doi: 10.1186/s12987-015-0024-8 . PMC 4677451 . PMID 26652013.

- ↑ Fabio Duranti; Massimo Pieri; Rossella Zenobi; Diego Centonze; Fabio Buttari; Sergio Bernardini; Mariarita Dessi. "kFLC Index: a novel approach in early diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis". International Journal of Scientific Research. 4 (8).

- ↑ Serafeim, Katsavos; Anagnostouli Maria (2013). "Biomarkers in Multiple Sclerosis: An Up-to-Date Overview". Multiple Sclerosis International. 2013: 340508. doi: 10.1155/2013/340508 . PMC 3564381 . PMID 23401777.

- ↑ Carlson NG, Rose JW (2013). "Vitamin D as a clinical biomarker in multiple sclerosis". Expert Opin Med Diagn (Review). 7 (3): 231–42. doi:10.1517/17530059.2013.772978. PMID 23480560.

- ↑ Wootla B, Eriguchi M, Rodriguez M (2012). "Is multiple sclerosis an autoimmune disease?". Autoimmune Diseases. 2012: 969657. doi: 10.1155/2012/969657 . PMC 3361990 . PMID 22666554.

- ↑ Buck Dorothea; Hemmer Bernhard (2014). "Biomarkers of treatment response in multiple sclerosis". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 14 (2): 165–172. doi:10.1586/14737175.2014.874289. PMID 24386967. S2CID 10295564.

- ↑ Comabella Manuel; Montalban Xavier (2014). "Body fluid biomarkers in multiple sclerosis". The Lancet Neurology. 13 (1): 113–126. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70233-3. PMID 24331797. S2CID 34302527.

- ↑ Salehi, Zahra; Doosti, Rozita; Beheshti, Masoumeh; Janzamin, Ehsan; Sahraian, Mohammad Ali; Izad, Maryam (2016). "Differential Frequency of CD8+ T Cell Subsets in Multiple Sclerosis Patients with Various Clinical Patterns". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0159565. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1159565S. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159565 . PMC 4965085 . PMID 27467597.

- ↑ Lockwood, Sarah Y.; Summers, Suzanne; Eggenberger, Eric; Spence, Dana M. (2016). "An in Vitro Diagnostic for Multiple Sclerosis Based on C-peptide Binding to Erythrocytes". eBioMedicine. 11: 249–252. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.07.036. PMC 5049924 . PMID 27528268.

- ↑ Lehmann-Werman, Roni; Neiman, Daniel; Zemmour, Hai; Moss, Joshua; Magenheim, Judith; Vaknin-Dembinsky, Adi; Rubertsson, Sten; Nellgård, Bengt; Blennow, Kaj; Zetterberg, Henrik; Spalding, Kirsty; Haller, Michael J.; Wasserfall, Clive H.; Schatz, Desmond A.; Greenbaum, Carla J.; Dorrell, Craig; Grompe, Markus; Zick, Aviad; Hubert, Ayala; Maoz, Myriam; Fendrich, Volker; Bartsch, Detlef K.; Golan, Talia; Ben Sasson, Shmuel A.; Zamir, Gideon; Razin, Aharon; Cedar, Howard; Shapiro, A. M. James; Glaser, Benjamin; et al. (2016). "Identification of tissue-specific cell death using methylation patterns of circulating DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (13): E1826–E1834. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113E1826L. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519286113 . PMC 4822610 . PMID 26976580.

- ↑ Hammack, B. N.; Fung, K. Y.; Hunsucker, S. W.; Duncan, M. W.; Burgoon, M. P.; Owens, G. P.; Gilden, D. H. (Jun 2004). "Proteomic analysis of multiple sclerosis cerebrospinal fluid". Mult Scler. 10 (3): 245–60. doi:10.1191/1352458504ms1023oa. PMID 15222687. S2CID 37117616.

- 1 2 3 Pavelek Zbysek; et al. (2016). "Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and clinically isolated syndrome". Biomedical Reports. 5 (1): 35–40. doi:10.3892/br.2016.668. PMC 4906564 . PMID 27347402.

- ↑ Bergman, Joakim; Dring, Ann; Zetterberg, Henrik; Blennow, Kaj; Norgren, Niklas; Gilthorpe, Jonathan; Bergenheim, Tommy; Svenningsson, Anders (2016). "Neurofilament light in CSF and serum is a sensitive marker for axonal white matter injury in MS". Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation. 3 (5): e271. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000271. PMC 4972001 . PMID 27536708.

- ↑ Klistornera Alexander; et al. (2016). "Diffusivity in multiple sclerosis lesions: At the cutting edge?". NeuroImage: Clinical. 12: 219–226. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2016.07.003. PMC 4950592 . PMID 27489769.

- ↑ Stephanie Meier; et al. (2023). "Serum Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Compared With Neurofilament Light Chain as a Biomarker for Disease Progression in Multiple Sclerosis". JAMA Neurology. 80 (3): 287–297. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.5250. PMC 10011932 . PMID 36745446.

- ↑ Spadaro Melania; et al. (2016). "Autoantibodies to MOG in a distinct subgroup of adult multiple sclerosis". Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 3 (5): e257. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000257. PMC 4949775 . PMID 27458601.

- ↑ Happe, LE (Nov 2013). "Choosing the best treatment for multiple sclerosis: comparative effectiveness, safety, and other factors involved in disease-modifying therapy choice". Am J Manag Care. 19 (17 Suppl): S332–42. PMID 24494634.

- ↑ Finn, Robert (21 May 2015). "Gene Variant Associated with Non-Response to Interferon β". Multiple Sclerosis Discovery Forum. doi: 10.7493/msdf.10.18998.1 .

- 1 2 Esposito, Federica; Sorosina, Melissa; Ottoboni, Linda; Lim, Elaine T.; Replogle, Joseph M.; Raj, Towfique; Brambilla, Paola; Liberatore, Giuseppe; Guaschino, Clara; Romeo, Marzia; Pertel, Thomas; Stankiewicz, James M.; Martinelli, Vittorio; Rodegher, Mariaemma; Weiner, Howard L.; Brassat, David; Benoist, Christophe; Patsopoulos, Nikolaos A.; Comi, Giancarlo; Elyaman, Wassim; Martinelli Boneschi, Filippo; De Jager, Philip L. (2015). "A pharmacogenetic study implicatesSLC9a9in multiple sclerosis disease activity". Annals of Neurology. 78 (1): 115–127. doi: 10.1002/ana.24429 . PMID 25914168. S2CID 3210890.

- ↑ Parnell, GP (Jan 2014). "The autoimmune disease-associated transcription factors EOMES and TBX21 are dysregulated in multiple sclerosis and define a molecular subtype of disease". Clin Immunol. 151 (1): 16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.01.003 . PMID 24495857.

- ↑ Hellberg, Sandra; Eklund, Daniel; Gawel, Danuta R.; Köpsén, Mattias; Zhang, Huan; Nestor, Colm E.; Kockum, Ingrid; Olsson, Tomas; Skogh, Thomas; Kastbom, Alf; Sjöwall, Christopher; Vrethem, Magnus; Håkansson, Irene; Benson, Mikael; Jenmalm, Maria C.; Gustafsson, Mika; Ernerudh, Jan (2016). "Dynamic Response Genes in CD4+ T Cells Reveal a Network of Interactive Proteins that Classifies Disease Activity in Multiple Sclerosis". Cell Reports. 16 (11): 2928–2939. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.036 . PMID 27626663.

- ↑ Warabi Yoko; et al. (2016). "Spinal cord open-ring enhancement in multiple sclerosis with marked effect of fingolimod". Clinical and Experimental Neuroimmunology. 7 (4): 353–354. doi:10.1111/cen3.12322. S2CID 78240891.

- ↑ Gross; et al. (2016). "Distinct pattern of lesion distribution in multiple sclerosis is associated with different circulating T-helper and helper-like innate lymphoid cell subsets". Mult Scler. 23 (7): 1025–1030. doi:10.1177/1352458516662726. PMID 27481205. S2CID 3949451.

- ↑ Johnson, Mark C.; Pierson, Emily R.; Spieker, Andrew J.; Nielsen, A. Scott; Posso, Sylvia; Kita, Mariko; Buckner, Jane H.; Goverman, Joan M. (2016). "Distinct T cell signatures define subsets of patients with multiple sclerosis". Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation. 3 (5): e278. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000278. PMC 4996538 . PMID 27606354.

- ↑ while others were irresponsive

- ↑ United States patent US9267945

- ↑ Hegen, Harald; et al. (2016). "Cytokine profiles show heterogeneity of interferon-β response in multiple sclerosis patients". Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 3 (2): e202. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000202. PMC 4747480 . PMID 26894205.

- ↑ Matas, Elisabet; Bau, Laura; Martínez-Iniesta, María; Romero-Pinel, Lucía; Mañé-Martínez, M. Alba; Cobo-Calvo, Álvaro; Martínez-Yélamos, Sergio (2016). "MxA mRNA expression as a biomarker of interferon beta response in multiple sclerosis patients". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 291: 73–77. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.12.015. PMID 26857498. S2CID 24389171.

- ↑ Miyazaki, T; Nakajima, H; Motomura, M; Tanaka, K (2016). "A case of recurrent optic neuritis associated with cerebral and spinal cord lesions and autoantibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein relapsed after fingolimod therapy". Clinical Neurology. 56 (4): 265–269. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.cn-000756 . PMID 27010093.

- ↑ Wootla B, Eriguchi M, Rodriguez M (2012). "Is multiple sclerosis an autoimmune disease?". Autoimmune Diseases. 2012: 969657. doi: 10.1155/2012/969657 . PMC 3361990 . PMID 22666554.

- ↑ Buck Dorothea; Hemmer Bernhard (2014). "Biomarkers of treatment response in multiple sclerosis". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 14 (2): 165–172. doi:10.1586/14737175.2014.874289. PMID 24386967. S2CID 10295564.

- ↑ Comabella Manuel; Montalban Xavier (2014). "Body fluid biomarkers in multiple sclerosis". The Lancet Neurology. 13 (1): 113–126. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70233-3. PMID 24331797. S2CID 34302527.

- ↑ Dobson, Ruth; Ramagopalan, Sreeram; Davis, Angharad; Giovannoni, Gavin (August 2013). "Cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal bands in multiple sclerosis and clinically isolated syndromes: a meta-analysis of prevalence, prognosis and effect of latitude". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 84 (8): 909–914. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-304695. ISSN 1468-330X. PMID 23431079. S2CID 19005640.

- ↑ Villar, L. M.; Masjuan, J.; González-Porqué, P.; Plaza, J.; Sádaba, M. C.; Roldán, E.; Bootello, A.; Alvarez-Cermeño, J. C. (2002-08-27). "Intrathecal IgM synthesis predicts the onset of new relapses and a worse disease course in MS". Neurology. 59 (4): 555–559. doi:10.1212/wnl.59.4.555. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 12196648. S2CID 41768095.

- ↑ Brettschneider, Johannes; Tumani, Hayrettin; Kiechle, Ulrike; Muche, Rainer; Richards, Gayle; Lehmensiek, Vera; Ludolph, Albert C.; Otto, Markus (2009-11-05). "IgG antibodies against measles, rubella, and varicella zoster virus predict conversion to multiple sclerosis in clinically isolated syndrome". PLOS ONE. 4 (11): e7638. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7638B. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007638 . ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2766627 . PMID 19890384.

- 1 2 3 Srivastava Rajneesh; et al. (2012). "Potassium Channel KIR4.1 as an Immune Target in Multiple Sclerosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (2): 115–123. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110740. PMC 5131800 . PMID 22784115.

- ↑ Bielekova, Bibiana; Martin, Roland (2004). "Development of biomarkers in multiple sclerosis". Brain. 127 (7): 1463–1478. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh176 . PMID 15180926.

- ↑ Hammack BN, Fung KY, Hunsucker SW, Duncan MW, Burgoon MP, Owens GP, Gilden DH (Jun 2004). "Proteomic analysis of multiple sclerosis cerebrospinal fluid". Mult Scler. 10 (3): 245–60. doi:10.1191/1352458504ms1023oa. PMID 15222687. S2CID 37117616.

- ↑ Hinsinger G, et al. (2015). "Chitinase 3-like proteins as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis". Mult Scler. 21 (10): 1251–61. doi:10.1177/1352458514561906. PMID 25698171. S2CID 27290546.

- ↑ Esposito, Federica; Sorosina, Melissa; Ottoboni, Linda; Lim, Elaine T.; Replogle, Joseph M.; Raj, Towfique; Brambilla, Paola; Liberatore, Giuseppe; Guaschino, Clara; Romeo, Marzia; Pertel, Thomas; Stankiewicz, James M.; Martinelli, Vittorio; Rodegher, Mariaemma; Weiner, Howard L.; Brassat, David; Benoist, Christophe; Patsopoulos, Nikolaos A.; Comi, Giancarlo; Elyaman, Wassim; Martinelli Boneschi, Filippo; De Jager, Philip L. (2015). "A pharmacogenetic study implicatesSLC9a9in multiple sclerosis disease activity". Annals of Neurology. 78 (1): 115–27. doi: 10.1002/ana.24429 . PMID 25914168. S2CID 3210890.

- ↑ Haufschild T, Shaw SG, Kesselring J, Flammer J (Mar 2001). "Increased endothelin-1 plasma levels in patients with multiple sclerosis". J Neuroophthalmol. 21 (1): 37–8. doi:10.1097/00041327-200103000-00011. PMID 11315981. S2CID 24772967.

- ↑ Kanabrocki EL, Ryan MD, Hermida RC, et al. (2008). "Uric acid and renal function in multiple sclerosis". Clin Ter. 159 (1): 35–40. PMID 18399261.

- ↑ Yang L, Anderson DE, Kuchroo J, Hafler DA (2008). "Lack of TIM-3 Immunoregulation in Multiple Sclerosis". Journal of Immunology. 180 (7): 4409–4414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4409 . PMID 18354161.

- ↑ Malmeström C, Lycke J, Haghighi S, Andersen O, Carlsson L, Wadenvik H, Olsson B (2008). "Relapses in multiple sclerosis are associated with increased CD8(+) T-cell mediated cytotoxicity in CSF". J. Neuroimmunol. 196 (Apr.5): 35–40. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.03.001. PMID 18396337. S2CID 206272331.

- 1 2 Satoh J (2008). "[Molecular biomarkers for prediction of multiple sclerosis relapse]". Nippon Rinsho (in Japanese). 66 (6): 1103–11. PMID 18540355.

- ↑ Sheremata WA, Jy W, Horstman LL, Ahn YS, Alexander JS, Minagar A (2008). "Evidence of platelet activation in multiple sclerosis". J Neuroinflammation. 5 (1): 27. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-27 . PMC 2474601 . PMID 18588683.

- ↑ Astier AL (2008). "T-cell regulation by CD46 and its relevance in multiple sclerosis". Immunology. 124 (2): 149–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02821.x. PMC 2566619 . PMID 18384356.

- ↑ Kanabrocki EL, Ryan MD, Lathers D, Achille N, Young MR, Cauteren JV, Foley S, Johnson MC, Friedman NC, Siegel G, Nemchausky BA (2007). "Circadian distribution of serum cytokines in multiple sclerosis". Clin. Ter. 158 (2): 157–62. PMID 17566518.

- ↑ Rentzos M, Nikolaou C, Rombos A, Evangelopoulos ME, Kararizou E, Koutsis G, Zoga M, Dimitrakopoulos A, Tsoutsou A, Sfangos C (2008). "Effect of treatment with methylprednisolone on the serum levels of IL-12, IL-10 and CCL2 chemokine in patients with multiple sclerosis in relapse". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 110 (10): 992–6. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.06.005. PMID 18657352. S2CID 2630371.

- ↑ Scarisbrick IA, Linbo R, Vandell AG, Keegan M, Blaber SI, Blaber M, Sneve D, Lucchinetti CF, Rodriguez M, Diamandis EP (2008). "Kallikreins are associated with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and promote neurodegeneration". Biological Chemistry. 389 (6): 739–45. doi:10.1515/BC.2008.085. PMC 2580060 . PMID 18627300.

- ↑ New Control System Of The Body Discovered - Important Modulator Of Immune Cell Entry Into The Brain - Perhaps New Target For The Therapy, Dr. Ulf Schulze-Topphoff, Prof. Orhan Aktas, and Professor Frauke Zipp (Cecilie Vogt-Clinic, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) Berlin-Buch and NeuroCure Research Center)

- ↑ Schulze-Topphoff U, Prat A, Prozorovski T, et al. (July 2009). "Activation of kinin receptor B1 limits encephalitogenic T lymphocyte recruitment to the central nervous system". Nat. Med. 15 (7): 788–93. doi:10.1038/nm.1980. PMC 4903020 . PMID 19561616.

- ↑ Rinta S, Kuusisto H, Raunio M, et al. (October 2008). "Apoptosis-related molecules in blood in multiple sclerosis". J. Neuroimmunol. 205 (1–2): 135–41. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.09.002. PMID 18963025. S2CID 28592242.

- ↑ Kuenz B, Lutterotti A, Ehling R, et al. (2008). Zimmer J (ed.). "Cerebrospinal Fluid B Cells Correlate with Early Brain Inflammation in Multiple Sclerosis". PLOS ONE. 3 (7): e2559. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2559K. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002559 . PMC 2438478 . PMID 18596942.

- ↑ Chiasserini D, Di Filippo M, Candeliere A, Susta F, Orvietani PL, Calabresi P, Binaglia L, Sarchielli P (2008). "CSF proteome analysis in multiple sclerosis patients by two-dimensional electrophoresis". European Journal of Neurology. 15 (9): 998–1001. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02239.x. PMID 18637954. S2CID 27735092.

- ↑ Frisullo G, Nociti V, Iorio R, et al. (October 2008). "The persistency of high levels of pSTAT3 expression in circulating CD4+ T cells from CIS patients favors the early conversion to clinically defined multiple sclerosis". J. Neuroimmunol. 205 (1–2): 126–34. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.09.003. PMID 18926576. S2CID 27303451.

- ↑ Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences, complementary information

- ↑ Quintana FJ, Farez MF, Viglietta V, et al. (December 2008). "Antigen microarrays identify unique serum autoantibody signatures in clinical and pathologic subtypes of multiple sclerosis". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (48): 18889–94. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10518889Q. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806310105 . PMC 2596207 . PMID 19028871.

- ↑ Villar LM, Masterman T, Casanova B, et al. (June 2009). "CSF oligoclonal band patterns reveal disease heterogeneity in multiple sclerosis". J. Neuroimmunol. 211 (1–2): 101–4. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.03.003. PMID 19443047. S2CID 31814258.

- ↑ Martin Nellie A., Illes Zsolt (2014). "Differentially expressed microRNA in multiple sclerosis: A window into pathogenesis?". Clinical and Experimental Neuroimmunology. 5 (2): 149–161. doi:10.1111/cen3.12131. S2CID 84623296.

- ↑ Gandhi R, Healy B, Gholipour T, Egorova S, Musallam A, Hussain MS, Nejad P, Patel B, Hei H, Khoury S, Quintana F, Kivisakk P, Chitnis T, Weiner HL (Jun 2013). "Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers for disease staging in multiple sclerosis". Ann Neurol. 73 (6): 729–40. doi: 10.1002/ana.23880 . PMID 23494648. S2CID 205344499.

- ↑ Bergman P, Piket E, Khademi M, James T, Brundin L, Olsson T, Piehl F, Jagodic M (2016). "Circulating miR-150 in CSF is a novel candidate biomarker for multiple sclerosis". Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 3 (3): e219. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000219. PMC 4841644 . PMID 27144214.

- ↑ Quintana E, et al. (2017). "miRNAs in cerebrospinal fluid identify patients with MS and specifically those with lipid-specific oligoclonal IgM bands". Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 23 (13): 1716–1726. doi:10.1177/1352458516684213. PMID 28067602. S2CID 23439273.

- ↑ Jagot, Ferdinand; Davoust, Nathalie (2016). "Is It worth Considering Circulating microRNAs in Multiple Sclerosis?". Frontiers in Immunology. 7: 129. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00129 . PMC 4821089 . PMID 27092141.

- ↑ Huang, Qingrong; Xiao, Bo; Ma, Xinting; Qu, Mingjuan; Li, Yanmin; Nagarkatti, Prakash; Nagarkatti, Mitzi; Zhou, Juhua (2016). "MicroRNAs associated with the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 295–296: 148–161. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.04.014. PMID 27235360. S2CID 37072576.

- ↑ Ottoboni L, Keenan BT, Tamayo P, Kuchroo M, Mesirov JP, Buckle GJ, Khoury SJ, Hafler DA, Weiner HL, De Jager PL (2012). "An RNA Profile Identifies Two Subsets of Multiple Sclerosis Patients Differing in Disease Activity". Sci Transl Med. 4 (153): 153ra131. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004186. PMC 3753678 . PMID 23019656.

- ↑ Parnell GP, Gatt PN, Krupa M, Nickles D, McKay FC, Schibeci SD, Batten M, Baranzini S, Henderson A, Barnett M, Slee M, Vucic S, Stewart GJ, Booth DR, et al. (2014). "The autoimmune disease-associated transcription factors EOMES and TBX21 are dysregulated in multiple sclerosis and define a molecular subtype of disease". Clinical Immunology. 151 (1): 16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.01.003 . PMID 24495857.

- ↑ Wang Zhe; et al. (2016). "Nuclear Receptor NR1H3 in Familial Multiple Sclerosis". Neuron. 90 (5): 948–954. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.039. PMC 5092154 . PMID 27253448.

- ↑ Plumb J, McQuaid S, Mirakhur M, Kirk J (April 2002). "Abnormal endothelial tight junctions in active lesions and normal-appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis". Brain Pathol. 12 (2): 154–69. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00430.x. PMC 8095734 . PMID 11958369.

- ↑ Mancini, M, Cerebral circulation time in the evaluation of neurological diseases

- ↑ Meng Law et al. Microvascular Abnormality in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Perfusion MR Imaging Findings in Normal-appearing White Matter

- ↑ Orbach, Rotem; Gurevich, Michael; Achiron, Anat (2014). "Interleukin-12p40 in the spinal fluid as a biomarker for clinically isolated syndrome". Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 20 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1177/1352458513491166. PMID 23722323. S2CID 23277386.

- ↑ Jarius S, Eichhorn P, Franciotta D, et al. (2016). "The MRZ reaction as a highly specific marker of multiple sclerosis: re-evaluation and structured review of the literature". J. Neurol. 264 (3): 453–466. doi:10.1007/s00415-016-8360-4. PMID 28005176. S2CID 25322362.

- ↑ Sarchielli P, Greco L, Floridi A, Floridi A, Gallai V (2003). "Excitatory amino acids and multiple sclerosis: evidence from cerebrospinal fluid". Arch. Immunol. 60 (8): 1082–8. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.8.1082. PMID 12925363.

- ↑ Kostic Milos; et al. (2017). "IL-17 signalling in astrocytes promotes glutamate excitotoxicity: Indications for the link between inflammatory and neurodegenerative events in multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 11: 12–17. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2016.11.006. PMID 28104249.

- ↑ Frigo M, Cogo MG, Fusco ML, Gardinetti M, Frigeni B (2012). "Glutamate and multiple sclerosis". Curr. Med. Chem. 19 (9): 1295–9. doi:10.2174/092986712799462559. PMID 22304707.

- ↑ Pitt David; et al. (2003). "Glutamate uptake by oligodendrocytes". Neurology. 61 (8): 1113–1120. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000090564.88719.37. PMID 14581674. S2CID 42422422.

- ↑ Stoop MP, Dekker LJ, Titulaer MK, et al. (2008). "Multiple sclerosis-related proteins identified in cerebrospinal fluid by advanced mass spectrometry". Proteomics. 8 (8): 1576–85. doi:10.1002/pmic.200700446. PMID 18351689. S2CID 41766020.

- ↑ Sarchielli P, Di Filippo M, Ercolani MV, et al. (April 2008). "Fibroblast growth factor-2 levels are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients". Neurosci. Lett. 435 (3): 223–8. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.040. PMID 18353554. S2CID 26004791.

- ↑ Sotelo J, Martínez-Palomo A, Ordoñez G, Pineda B (2008). "Varicella-zoster virus in cerebrospinal fluid at relapses of multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology. 63 (3): 303–11. doi:10.1002/ana.21316. PMID 18306233. S2CID 36489072.

- ↑ von Büdingen HC, Harrer MD, Kuenzle S, Meier M, Goebels N (July 2008). "Clonally expanded plasma cells in the cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients produce myelin-specific antibodies". European Journal of Immunology. 38 (7): 2014–23. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737784 . PMID 18521957.

- ↑ Vincze O, Oláh J, Zádori D, Klivényi P, Vécsei L, Ovádi J (May 2011). "A new myelin protein, TPPP/p25, reduced in demyelinated lesions is enriched in cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 409 (1): 137–41. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.130. PMID 21565174.

- ↑ Han, S.; Lin, Y. C.; Wu, T.; Salgado, A. D.; Mexhitaj, I.; Wuest, S. C.; Romm, E.; Ohayon, J.; Goldbach-Mansky, R.; Vanderver, A.; Marques, A.; Toro, C.; Williamson, P.; Cortese, I.; Bielekova, B. (2014). "Comprehensive Immunophenotyping of Cerebrospinal Fluid Cells in Patients with Neuroimmunological Diseases". The Journal of Immunology. 192 (6): 2551–63. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1302884. PMC 4045479 . PMID 24510966.

- ↑ Liguori, Maria; Qualtieri, Antonio; Tortorella, Carla; Direnzo, Vita; Bagalà, Angelo; Mastrapasqua, Mariangela; Spadafora, Patrizia; Trojano, Maria (2014). "Proteomic Profiling in Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Courses Reveals Potential Biomarkers of Neurodegeneration". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e103984. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j3984L. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103984 . PMC 4123901 . PMID 25098164.

- ↑ Burman; et al. (Oct 2014). "The cerebrospinal fluid cytokine signature of multiple sclerosis: A homogenous response that does not conform to the Th1/Th2/Th17 convention". J Neuroimmunol. 277 (1–2): 153–159. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.10.005. PMID 25457841. S2CID 206277371.

- ↑ Albanese Maria; et al. (2016). "Cerebrospinal fluid lactate is associated with multiple sclerosis disease progression". Journal of Neuroinflammation. 13: 36. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0502-1 . PMC 4750170 . PMID 26863878.

- ↑ Soelberg Sorensen Per, Sellebjerg Finn (2016). "Neurofilament in CSF—A biomarker of disease activity and long-term prognosis in multiple sclerosis". Mult Scler. 22 (9): 1112–3. doi: 10.1177/1352458516658560 . PMID 27364323.

- ↑ Delgado-García; et al. (2014). "A new risk variant for multiple sclerosis at the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus associates with intrathecal IgG, IgM index and oligoclonal bands". Mult Scler. 21 (9): 1104–1111. doi:10.1177/1352458514556302. hdl: 10261/133187 . PMID 25392328. S2CID 206701193.

- ↑ Huttner HB, Schellinger PD, Struffert T, et al. (July 2009). "MRI criteria in MS patients with negative and positive oligoclonal bands: equal fulfillment of Barkhof's criteria but different lesion patterns". J. Neurol. 256 (7): 1121–5. doi:10.1007/s00415-009-5081-y. PMID 19252765. S2CID 25553346.

- ↑ Villar, Luisa M.; Masterman, Thomas; Casanova, Bonaventura; Gómez-Rial, José; Espiño, Mercedes; Sádaba, María C.; González-Porqué, Pedro; Coret, Francisco; Álvarez-Cermeño, José C. (2009). "CSF oligoclonal band patterns reveal disease heterogeneity in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 211 (1–2): 101–4. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.03.003. PMID 19443047. S2CID 31814258.

- ↑ Wingera RC, Zamvil SS (2016). "Antibodies in multiple sclerosis oligoclonal bands target debris". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (28): 7696–8. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.7696W. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609246113 . PMC 4948325 . PMID 27357674.

- ↑ Villar LM, Espiño M, Costa-Frossard L, Muriel A, Jiménez J, Alvarez-Cermeño JC (November 2012). "High levels of cerebrospinal fluid free kappa chains predict conversion to multiple sclerosis". Clin. Chim. Acta. 413 (23–24): 1813–6. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2012.07.007. PMID 22814197.

- ↑ Zaaraoui, Wafaa; Konstandin, Simon; Audoin, Bertrand; Nagel, Armin M.; Rico, Audrey; Malikova, Irina; Soulier, Elisabeth; Viout, Patrick; Confort-Gouny, Sylviane; Cozzone, Patrick J.; Pelletier, Jean; Schad, Lothar R.; Ranjeva, Jean-Philippe (2012). "Distribution of Brain Sodium Accumulation Correlates with Disability in Multiple Sclerosis: A Cross-sectional23Na MR Imaging Study". Radiology. 264 (3): 859–867. doi:10.1148/radiol.12112680. PMID 22807483.

- ↑ Bsibsi M, Holtman IR, Gerritsen WH, Eggen BJ, Boddeke E, van der Valk P, van Noort JM, Amor S (2013). "Alpha-B-Crystallin Induces an Immune-Regulatory and Antiviral Microglial Response in Preactive Multiple Sclerosis Lesions". J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 72 (10): 970–9. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182a776bf . PMID 24042199.

- ↑ Manogaran, Praveena; Traboulsee, Anthony L.; Lange, Alex P. (2016). "Longitudinal Study of Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness and Macular Volume in Patients with Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder". Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 36 (4): 363–368. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000404. PMID 27416520. S2CID 22865622.

- ↑ Tejera-Alhambra, Marta; Casrouge, Armanda; De Andrés, Clara; Seyfferth, Ansgar; Ramos-Medina, Rocío; Alonso, Bárbara; Vega, Janet; Fernández-Paredes, Lidia; Albert, Matthew L.; Sánchez-Ramón, Silvia (2015). "Plasma Biomarkers Discriminate Clinical Forms of Multiple Sclerosis". PLOS ONE. 10 (6): e0128952. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1028952T. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128952 . PMC 4454618 . PMID 26039252.

- ↑ Cramer SP, Modvig S, Simonsen HJ, Frederiksen JL, Larsson HB (Jul 2015). "Permeability of the blood-brain barrier predicts conversion from optic neuritis to multiple sclerosis". Brain. 138 (Pt 9): 2571–83. doi:10.1093/brain/awv203. PMC 4547053 . PMID 26187333.

- ↑ Beggs CB, Shepherd SJ, Dwyer MG, Polak P, Magnano C, Carl E, Poloni GU, Weinstock-Guttman B, Zivadinov R (Oct 2012). "Sensitivity and specificity of SWI venography for detection of cerebral venous alterations in multiple sclerosis". Neurol Res. 34 (8): 793–801. doi:10.1179/1743132812Y.0000000048. PMID 22709857. S2CID 10318031.

- ↑ Laule C, et al. (Aug 2003). "Evolution of focal and diffuse magnetisation transfer abnormalities in multiple sclerosis". J Neurol. 250 (8): 924–31. doi:10.1007/s00415-003-1115-z. PMID 12928910. S2CID 13407228.

- ↑ Park, Eunkyung; Gallezot, Jean-Dominique; Delgadillo, Aracely; Liu, Shuang; Planeta, Beata; Lin, Shu-Fei; o'Connor, Kevin C.; Lim, Keunpoong; Lee, Jae-Yun; Chastre, Anne; Chen, Ming-Kai; Seneca, Nicholas; Leppert, David; Huang, Yiyun; Carson, Richard E.; Pelletier, Daniel (2015). "11C-PBR28 imaging in multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls: Test-retest reproducibility and focal visualization of active white matter areas". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 42 (7): 1081–1092. doi:10.1007/s00259-015-3043-4. PMID 25833352. S2CID 21974135.

- ↑ Airas, L.; Rissanen, E.; Rinne, J. (2016). "Imaging of microglial activation in MS using PET: Research use and potential future clinical application". Mult. Scler. 23 (Oct 19): 496–504. doi: 10.1177/1352458516674568 . PMID 27760860.

- ↑ Herranz, Elena; Giannì, Costanza; Louapre, Céline; Treaba, Constantina A.; Govindarajan, Sindhuja T.; Ouellette, Russell; Loggia, Marco L; Sloane, Jacob A.; Madigan, Nancy; Izquierdo-Garcia, David; Ward, Noreen; Mangeat, Gabriel; Granberg, Tobias; Klawiter, Eric C.; Catana, Ciprian; Hooker, Jacob M; Taylor, Norman; Ionete, Carolina; Kinkel, Revere P.; Mainero, Caterina (2016). "The neuroinflammatory component of gray matter pathology in multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology. 80 (5): 776–790. doi:10.1002/ana.24791. PMC 5115951 . PMID 27686563.

- ↑ Venneti, Sriram; Lopresti, Brian; Wiley, Clayton (2013). "Molecular imaging of microglia/macrophages in the brain". Glia. 61 (1): 10–23. doi:10.1002/glia.22357. PMC 3580157 . PMID 22615180.

- ↑ García-Barragán N, Villar LM, Espiño M, Sádaba MC, González-Porqué P, Alvarez-Cermeño JC (March 2009). "Multiple sclerosis patients with anti-lipid oligoclonal IgM show early favourable response to immunomodulatory treatment". Eur. J. Neurol. 16 (3): 380–5. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02504.x. PMID 19175382. S2CID 33302394.

- ↑ Hagman S, Raunio M, Rossi M, Dastidar P, Elovaara I (May 2011). "Disease-associated inflammatory biomarker profiles in blood in different subtypes of multiple sclerosis: Prospective clinical and MRI follow-up study". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 234 (1–2): 141–7. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.02.009. PMID 21397339. S2CID 45101259.

- ↑ Kuerten, Stefanie; Pommerschein, Giovanna; Barth, Stefanie K.; Hohmann, Christopher; Milles, Bianca; Sammer, Fabian W.; Duffy, Cathrina E.; Wunsch, Marie; Rovituso, Damiano M.; Schroeter, Michael; Addicks, Klaus; Kaiser, Claudia C.; Lehmann, Paul V. (2014). "Identification of a B cell-dependent subpopulation of multiple sclerosis by measurements of brain-reactive B cells in the blood". Clinical Immunology. 152 (1–2): 20–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.02.014 . PMID 24607792.

- ↑ University of Zurich (2018, October 11). Link Between Gut Flora and Multiple Sclerosis Discovered. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved October 11, 2018

- ↑ Planas, Raquel; Santos, Radleigh; Tomas-Ojer, Paula; Cruciani, Carolina; Lutterotti, Andreas; Faigle, Wolfgang; Schaeren-Wiemers, Nicole; Espejo, Carmen; Eixarch, Herena; Pinilla, Clemencia; Martin, Roland; Sospedra, Mireia (2018). "GDP-l-fucose synthase is a CD4+ T cell–specific autoantigen in DRB3*02:02 patients with multiple sclerosis" (PDF). Science Translational Medicine. 10 (462): eaat4301. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat4301 . PMID 30305453.

- ↑ Hegen Harald; et al. (2016). "Cytokine profiles show heterogeneity of interferon-β response in multiple sclerosis patients". Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 3 (2): e202. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000202. PMC 4747480 . PMID 26894205.

- ↑ Matas, Elisabet; Bau, Laura; Martínez-Iniesta, María; Romero-Pinel, Lucía; Mañé-Martínez, M. Alba; Cobo-Calvo, Álvaro; Martínez-Yélamos, Sergio (2016). "MxA mRNA expression as a biomarker of interferon beta response in multiple sclerosis patients". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 291: 73–7. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.12.015. PMID 26857498. S2CID 24389171.