Herāt is an oasis city and the third-largest city of Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated in the fertile valley of the Hari River in the western part of the country. An ancient civilization on the Silk Road between the Middle East, Central and South Asia, it serves as a regional hub in the country's west, and its historic Persian influences has given it the nickname as Afghanistan's Little Iran.

The Timurid Empire, self-designated as Gurkani, was a Persianate Turco-Mongol empire comprising modern-day Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Iran, the southern region of the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, Afghanistan, much of Central Asia, as well as parts of contemporary India, Pakistan, Syria, and Turkey.

Shah Rukh was the ruler of the Timurid Empire between 1405 and 1447.

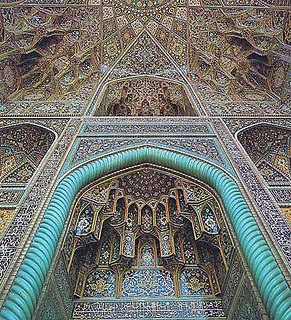

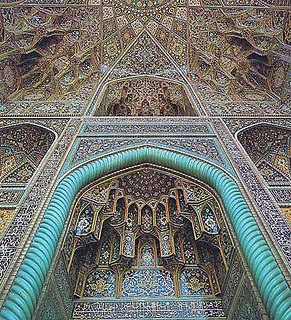

Goharshad Mosque is a grand congregational mosque built during the Timurid period in Mashhad, Razavi Khorasan Province, Iran, which now serves as one of the prayer halls within the Imam Reza shrine complex.

Gawhar Shad was the chief consort of Shah Rukh, the emperor of the Timurid Empire.

Architecture of Central Asia refers to the architectural styles of the numerous societies that have occupied Central Asia throughout history. These styles include Timurid architecture of the 14th and 15th centuries, Islamic-influenced Persian architecture and 20th century Soviet Modernism. Central Asia is an area that encompasses land from the Xinjiang Province of China in the East to the Caspian Sea in the West. The region is made up of the countries of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan. The influence of Timurid Architecture can be recognised in numerous sites in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, whilst the influence of Persian Architecture is seen frequently in Uzbekistan and in some examples in Turkmenistan. Examples of Soviet Architecture can be found in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

The Great Mosque of Herat or "Jami Masjid of Herat", is a mosque in the city of Herat, in the Herat Province of north-western Afghanistan. It was built by the Ghurids, under the rule of Sultan Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad Ghori, who laid its foundation in 1200 CE. Later, it was extended several times as Herat changed rulers down the centuries from the Kartids, Timurids, Mughals and then the Uzbeks, all of whom supported the mosque. The fundamental structure of the mosque from the Ghurid period has been preserved, but parts have been added and modified. The Friday Mosque in Herat was given its present appearance during the 20th century.

Ghiyath ud-din Baysunghur, commonly known as Baysonqor or Baysongor, Baysonghor or (incorrectly) as Baysunqar, also called Sultan Bāysonḡor Bahādor Khan was a prince from the house of Timurids. He was known as a patron of arts and architecture, the leading patron of the Persian miniature in Iran, commissioning the Baysonghor Shahnameh and other works, as well as being a prominent calligrapher.

Abu Sa'id Mirza was the ruler of the Timurid Empire during the mid-fifteenth century.

With the death of Shah Rukh in 1447 began the long drawn out Second Timurid Succession Crisis. His only surviving heir was his son Ulugh Beg who was at that time viceroy of Central Asia at Samarkand. Gawhar Shad and Abdal-Latif Mirza were with Shah Rukh when he died on his way back to Khurasan from Iran. Abdal-Latif Mirza became the commander of his grandfather's army and in conjunction with his father Ulugh Beg began operations against his cousins. As soon as Ulugh Beg heard of his father's death, he mobilized his forces and reached Amu Darya in order to take Balkh from his nephews. Balkh belonged to Ulugh Beg's brother Muhammad Juki who died in 1444. Balkh was divided among his sons Mirza Muhammad Qasim and Mirza Abu Bakr. However, Mirza Abu Bakr took his older brothers' possessions when Shah Rukh Mirza died. Ulugh Beg summoned Abu Bakr to his court and promised him his daughter in marriage. But while there he had him convicted of plotting against him and imprisoned at Kok Serai in Samarkand where he was later executed. Ulugh Beg then marched on Balkh and took that province unopposed.

Persian domes or Iranian domes have an ancient origin and a history extending to the modern era. The use of domes in ancient Mesopotamia was carried forward through a succession of empires in the Greater Iran region.

The Timurid Renaissance was a historical period in Asian and Islamic history spanning the late 14th, the 15th, and the early 16th centuries. Following the gradual downturn of the Islamic Golden Age, the Timurid Empire, based in Central Asia ruled by the Timurid dynasty, witnessed the revival of arts and sciences in the Muslim world. Its movement spread across the Muslim world and left profound impacts on late medieval Asia and Early Modern Period. The French word renaissance means "rebirth", and defines a period as one of cultural revival. The use of the term for the description of this period has raised reservations among scholars, some of whom see it as a swan song of Timurid culture.

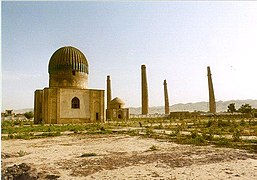

The Musalla Minarets of Herat are five huge ruined minaret towers in Herat city, western Afghanistan. The minarets and the complex were built by Queen Gawhar Shad in 1417.

The Shrine of Khwaja Abd Allah, commonly called the Shrine at Gazur Gah and the Abdullah Ansari Shrine Complex, is the funerary compound of the Sufi saint Khwaja Abdullah Ansari. It is located at the village of Gazur Gah, three kilometers northeast of Herat, Afghanistan. The Historic Cities Programme of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture has initiated repairs on the complex since 2005.

Bayqara Mirza I was a Timurid prince and a grandson of the Central Asian conqueror Timur by his eldest son Umar Shaikh Mirza I.

The architecture of Afghanistan refers to architecture within the borders defining the modern country, with these remaining relatively unchanged since 1834. As the connection between the three major cultural and geographic centres of Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and the Iranian plateau, the boundaries of the region prior to this time changed with the rapid advancement of armies, with the land belonging to a vast range of empires over the last two millennia.

Rukn-ud-din Ala al-Dawla Mirza, also spelt Ala ud-Dawla and Ala ud-Daula, was a Timurid prince and a grandson of the Central Asian ruler Shah Rukh. Following his grandfather's death, Ala al-Dawla became embroiled in the ensuing succession struggle. Though he initially possessed a strategic advantage, he was eventually overtaken by his more successful rivals. Ala al-Dawla died in exile after numerous failed attempts to gain the throne.

Muhammad Juki Mirza was a Timurid prince and a son of the Central Asian ruler Shah Rukh. He served as one of his father's military commanders and may have been favoured as his preferred successor. However, he died of illness in 1445, predeceasing Shah Rukh by two years.

The Gawhar Shad Mausoleum, also known as the Tomb of Baysunghur, is an Islamic burial structure located in what is now Herat, Afghanistan. Built in the 15th century, the structure served as a royal tomb for members of the Timurid dynasty and is part of the Musalla Complex.

Malikat Agha was a Mongol princess as well as one of the empresses of Shah Rukh, ruler of the Timurid Empire.