Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In the United States, it is regarded as a standalone conflict under this name. Elsewhere it is usually viewed as the American theater of the War of the Spanish Succession. It is also known as the Third Indian War. In France it was known as the Second Intercolonial War.

King William's War was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg. It was the first of six colonial wars fought between New France and New England along with their respective Native allies before France ceded its remaining mainland territories in North America east of the Mississippi River in 1763.

Norridgewock was the name of both an Indigenous village and a band of the Abenaki Native Americans/First Nations, an Eastern Algonquian tribe of the United States and Canada. The French of New France called the village Kennebec. The tribe occupied an area in the interior of Maine. During colonial times, this area was territory disputed between British and French colonists, and was set along the claimed western border of Acadia, the western bank of the Kennebec River.

Dummer's War (1722–1725) was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the Wabanaki Confederacy, who were allied with New France. The eastern theater of the war was located primarily along the border between New England and Acadia in Maine, as well as in Nova Scotia; the western theater was located in northern Massachusetts and Vermont at the border between Canada and New England. During this time, Maine and Vermont were part of Massachusetts.

Samuel Shute was an English military officer and royal governor of the provinces of Massachusetts and New Hampshire. After serving in the Nine Years' War and the War of the Spanish Succession, he was appointed by King George I as governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire in 1716. His tenure was marked by virulent disagreements with the Massachusetts assembly on a variety of issues, and by poorly conducted diplomacy with respect to the Native American Wabanaki Confederacy of northern New England that led to Dummer's War (1722–1725).

Saint-François-du-Lac is a community in the Nicolet-Yamaska Regional County Municipality of Quebec, Canada. The population as of the Canada 2011 Census was 1,957. It is located at the confluence of the Saint Lawrence and Saint-François rivers, at the edge of Lac Saint-Pierre.

Sébastien Rale (also Racle, Râle, Rasle, Rasles, and Sebastian Rale was a French Jesuit missionary and lexicographer who preached amongst the Abenaki and encouraged their resistance to British colonization during the early 18th century. This encouragement culminated in Dummer's War, where Rale was killed by a group of New England militiamen. Rale also worked on an Abenaki-French dictionary during his time in North America.

The Treaty of Portsmouth, signed on July 13, 1713, ended hostilities between Eastern Abenakis, a Native American tribe and First Nation and Algonquian-speaking people, with the British provinces of Massachusetts Bay and New Hampshire. The agreement renewed a treaty of 1693 the natives had made with Governor Sir William Phips, two in a series of attempts to establish peace between the Wabanaki Confederacy and colonists after Queen Anne's War.

Colonial American military history is the military record of the Thirteen Colonies from their founding to the American Revolution in 1775.

The Battle of Winnepang occurred during Dummer's War when New England forces attacked Mi'kmaq at present day Jeddore Harbour, Nova Scotia. The naval battle was part of a campaign ordered by Governor Richard Philipps to retrieve over 82 New England prisoners taken by the Mi'kmaq in fishing vessels off the coast of Nova Scotia. The New England force was led by Ensign John Bradstreet and fishing Captain John Elliot.

The Battle of Pequawket occurred on May 9, 1725 (O.S.), during Father Rale's War in northern New England. Captain John Lovewell led a privately organized company of scalp hunters, organized into a makeshift ranger company, and Chief Paugus led the Abenaki at Pequawket, the site of present-day Fryeburg, Maine. The battle was related to the expansion of New England settlements along the Kennebec River.

The Northeast Coast campaign was the first major campaign by the French of Queen Anne's War in New England. Alexandre Leneuf de La Vallière de Beaubassin led 500 troops made up of French colonial forces and the Wabanaki Confederacy of Acadia. They attacked English settlements on the coast of present-day Maine between Wells and Casco Bay, burning more than 15 leagues of New England country and killing or capturing more than 150 people. The English colonists protected some of their settlements, but a number of others were destroyed and abandoned. Historian Samuel Drake reported that, "Maine had nearly received her death-blow" as a result of the campaign.

The Northeast Coast campaign (1745) occurred during King George's War from 19 July until 5 September 1745. Three weeks after the British Siege of Louisbourg (1745), the Wabanaki Confederacy of Acadia retaliated by attacking New England settlements along the coast of present-day Maine below the Kennebec River, the former border of Acadia. They attacked English settlements on the coast of present-day Maine between Berwick and St. Georges, within two months there were 11 raids - every town on the frontier had been attacked. Casco was the principal settlement.

The Northeast Coast campaign (1723) occurred during Father Rale's War from April 19, 1723 – January 28, 1724. In response to the previous year, in which New England attacked the Wabanaki Confederacy at Norridgewock and Penobscot, the Wabanaki Confederacy retaliated by attacking the coast of present-day Maine that was below the Kennebec River, the border of Acadia. They attacked English settlements on the coast of present-day Maine between Berwick and Mount Desert Island. Casco was the principal settlement. The 1723 campaign was so successful along the Maine frontier that Dummer ordered its evacuation to the blockhouses in the spring of 1724.

Mog (1663–1724), also called "Chief" Mog, Heracouansit, Warracansit, Warracunsit, or Warrawcuset, was an Abenaki Native American war leader who fought the British in North America during the early 18th century.

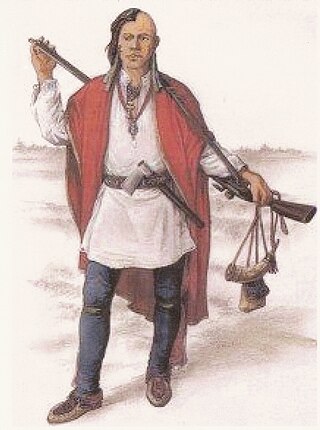

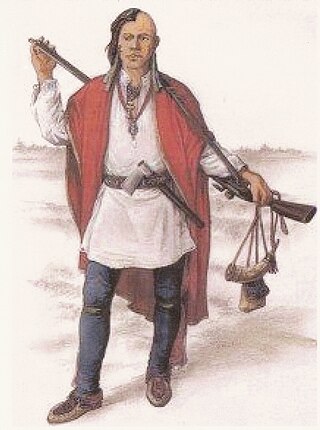

The military history of the Mi'kmaq consisted primarily of Mi'kmaq warriors (smáknisk) who participated in wars against the English independently as well as in coordination with the Acadian militia and French royal forces. The Mi'kmaq militias remained an effective force for over 75 years before the Halifax Treaties were signed (1760–1761). In the nineteenth century, the Mi'kmaq "boasted" that, in their contest with the British, the Mi'kmaq "killed more men than they lost". In 1753, Charles Morris stated that the Mi'kmaq have the advantage of "no settlement or place of abode, but wandering from place to place in unknown and, therefore, inaccessible woods, is so great that it has hitherto rendered all attempts to surprise them ineffectual". Leadership on both sides of the conflict employed standard colonial warfare, which included scalping non-combatants. After some engagements against the British during the American Revolutionary War, the militias were dormant throughout the nineteenth century, while the Mi'kmaq people used diplomatic efforts to have the local authorities honour the treaties. After confederation, Mi'kmaq warriors eventually joined Canada's war efforts in World War I and World War II. The most well-known colonial leaders of these militias were Chief (Sakamaw) Jean-Baptiste Cope and Chief Étienne Bâtard.

The Battle of Falmouth was fought at Falmouth, Maine when the Canadiens and Wabanaki Confederacy attacked the English New Casco Fort. The battle was part of the Northeast Coast Campaign (1703) during Queen Anne's War.

The Northeast Coast campaign of 1750 occurred during Father Le Loutre's War from 11 September to December 1750. The Norridgewock as well as the Abenaki from St. Francois and Trois-Rivières, Quebec raided British settlements along the Acadia/ New England border in present-day Maine.

Skowhegan is the county seat of Somerset County, Maine, United States. As of the 2020 census, the town population was 8,620. Every August, Skowhegan hosts the annual Skowhegan State Fair, the oldest continuously held state fair in the United States. Skowhegan was originally inhabited by the indigenous Abenaki people who named the area Skowhegan, meaning "watching place [for fish]," and were mostly dispersed by the end of the 4th Anglo-Abenaki War.

Colonel Johnson Harmon was an army officer in colonial America. He led the expedition during Father Rale's War that killed Father Sébastien Rale in the Battle of Norridgewock. Harmon was heralded as a hero upon his return to Boston. New England Officer and historian Samuel Penahallow proclaimed the attack was "the greatest victory we have obtained in the three or four last wars."