Driftwood Canyon Provincial Park is a provincial park in British Columbia, Canada. Driftwood Canyon Provincial Park covers 23 ha of the Bulkley River Valley, on the east side of Driftwood Creek, a tributary of the Bulkley River, 10 km northeast of the town of Smithers. The park is accessible from Driftwood Road from Provincial Highway 16. It was created in 1967 by the donation of the land by the late Gordon Harvey (1913–1976) to protect fossil beds on the east side of Driftwood Creek. The beds were discovered around the beginning of the 20th century. The park lands are part of the asserted traditional territory of the Wet'suwet'en First Nation.

Florissantia is an extinct genus of flowering plants in the Malvaceae subfamily Sterculioideae known from western North America and far eastern Asia. Flower, fruit, and pollen compression fossils have been found in formations ranging between the Early Eocene through to the Early Oligocene periods. The type species is Florissantia speirii and three additional species are known, Florissantia ashwillii, Florissantia quilchenensis, and Florissantia sikhote-alinensis.

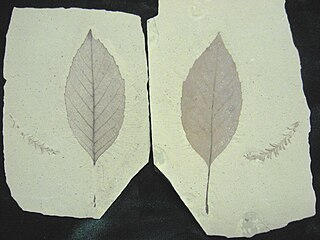

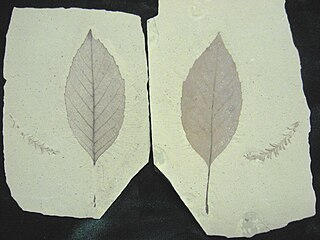

Sassafras hesperia is an extinct species of flowering plant in the family Lauraceae.

The Klondike Mountain Formation is an Early Eocene (Ypresian) geological formation located in the northeast central area of Washington state. The formation is comprised of volcanic rocks in the upper unit and volcanic plus lacustrine (lakebed) sedimentation in the lower unit. the formation is named for the type location designated in 1962, Klondike Mountain northeast of Republic, Washington. The formation is a lagerstätte with exceptionally well-preserved plant and insect fossils has been found, along with fossil epithermal hot springs.

The Allenby formation is a sedimentary rock formation in British Columbia which was deposited during the Ypresian stage of the Early Eocene. It consists of conglomerates, sandstones with interbedded shales and coal. The shales contain an abundance of insect, fish and plant fossils known from 1877 and onward, while the Princeton Chert was first indented in the 1950's and is known from anatomically preserved plants.

Taxodium dubium is an extinct species of cypress in the genus Taxodium in the family Cupressaceae which lived from the Late Paleocene to the Pliocene in North America and Europe. The species was first described in 1823 by Kaspar Maria von Sternberg.

Pseudolarix wehrii is an extinct species of golden larch in the pine family (Pinaceae). The species is known from early Eocene fossils of northern Washington state, United States, and southern British Columbia, Canada, along with late Eocene mummified fossils found in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada.

Comptonia columbiana is an extinct species of sweet fern in the flowering plant family Myricaceae. The species is known from fossil leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of central to southern British Columbia, Canada, plus northern Washington state, United States, and, tentatively, the late Eocene of Southern Idaho and Earliest Oligocene of Oregon, United States.

Amia? hesperia is an extinct species of bony fish in the bowfin family, Amiidae. The species is known from fossils found in the early Eocene deposits of northern Washington state in the United States and southeastern British Columbia. The species is one of eight fish species identified in the Eocene Okanagan Highlands paleofauna.

Acer spitzi is an extinct maple species in the family Sapindaceae described from a single fossil samara. The species is solely known from the Early Eocene sediments exposed in northeast Washington state, United States. It is the only species belonging to the extinct section Spitza.

Carpinus perryae is an extinct species of hornbeam known from fossil fruits found in the Klondike Mountain Formation deposits of northern Washington state, dated to the early Eocene Ypresian stage. Based on described features, C. perryae is the oldest definite species in the genus Carpinus.

Klondikia is an extinct hymenopteran genus in the ant family Formicidae with a single described species Klondikia whiteae. The species is solely known from the Early Eocene sediments exposed in northeast Washington state, United States. The genus is currently not placed into any ant subfamily, being treated as incertae sedis.

Equisetum similkamense is an extinct horsetail species in the family Equisetaceae described from a group of whole plant fossils including rhizomes, stems, and leaves. The species is known from Ypresian sediments exposed in British Columbia, Canada. It is one of several extinct species placed in the living genus Equisetum.

The paleoflora of the Eocene Okanagan Highlands includes all plant and fungi fossils preserved in the Eocene Okanagan Highlands Lagerstätten. The highlands are a series of Early Eocene geological formations which span an 1,000 km (620 mi) transect of British Columbia, Canada and Washington state, United States and are known for the diverse and detailed plant fossils which represent an upland temperate ecosystem immediately after the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum, and before the increased cooling of the middle and late Eocene to Oligocene. The fossiliferous deposits of the region were noted as early as 1873, with small amounts of systematic work happening in the 1880-90s on British Columbian sites, and 1920-30s for Washington sites. A returned focus and more detailed descriptive work on the Okanagan Highlands sites revived in the 1970's. The noted richness of agricultural plant families in Republic and Princeton floras resulted in the term "Eocene orchards" being used for the paleofloras.

Dipteronia brownii is an extinct species in the soapberry family (Sapindaceae) described in 2001. Fossils of D. brownii are known from stratigraphic formations in North America and Asia ranging in age between Paleocene to Early Oligocene.

Pteronepelys, sometimes known as the winged stranger, is an extinct genus of flowering plant of uncertain affinities, which contains the one species, Pteronepelys wehrii. It is known from isolated fossil seeds found in middle Eocene sediments exposed in north central Oregon and Ypresian-age fossils found in Washington, US.

The Eocene Okanagan Highlands or Eocene Okanogan Highlands are a series of Early Eocene geological formations which span a 1,000 km (620 mi) transect of British Columbia, Canada, and Washington state, United States. Known for a highly diverse and detailed plant and animal paleobiota the paleolake beds as a whole are considered one of the great Canadian Lagerstätten. The paleobiota represented are of an upland subtropical to temperate ecosystem series immediately after the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum, and before the increased cooling of the middle and late Eocene to Oligocene. The fossiliferous deposits of the region were noted as early as 1873, with small amounts of systematic work happening in the 1870–1920s on British Columbian sites, and 1920–1930s for Washington sites. Focus and more detailed descriptive work on the Okanagan Highland sites started in the late 1960s.

Alnus parvifolia is an extinct species of flowering plant in the family Betulaceae related to the modern birches. The species is known from fossil leaves and possible fruits found in early Eocene sites of northern Washington state, United States, and central British Columbia, Canada.