Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cretaceous period. More than 13,800 of an estimated total of 22,000 species have been classified. They are easily identified by their geniculate (elbowed) antennae and the distinctive node-like structure that forms their slender waists.

Symbiosis is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two biological organisms of different species, termed symbionts, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasitic. In 1879, Heinrich Anton de Bary defined it as "the living together of unlike organisms". The term is sometimes used in the more restricted sense of a mutually beneficial interaction in which both symbionts contribute to each other's support.

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthparts adapted to rasping or grinding. Horses and other herbivores have wide flat teeth that are adapted to grinding grass, tree bark, and other tough plant material.

Mutualism describes the ecological interaction between two or more species where each species has a net benefit. Mutualism is a common type of ecological interaction. Prominent examples are:

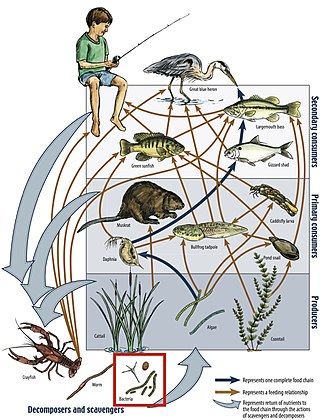

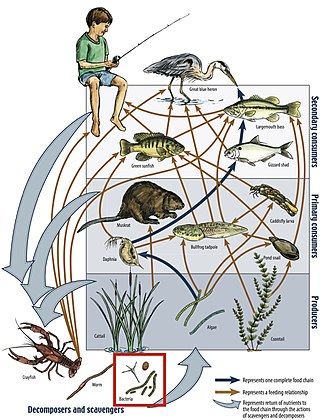

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Ecologists can broadly define all life forms as either autotrophs or heterotrophs, based on their trophic levels, the position that they occupy in the food web. To maintain their bodies, grow, develop, and to reproduce, autotrophs produce organic matter from inorganic substances, including both minerals and gases such as carbon dioxide. These chemical reactions require energy, which mainly comes from the Sun and largely by photosynthesis, although a very small amount comes from bioelectrogenesis in wetlands, and mineral electron donors in hydrothermal vents and hot springs. These trophic levels are not binary, but form a gradient that includes complete autotrophs, which obtain their sole source of carbon from the atmosphere, mixotrophs, which are autotrophic organisms that partially obtain organic matter from sources other than the atmosphere, and complete heterotrophs that must feed to obtain organic matter.

Hemiptera is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from 1 mm (0.04 in) to around 15 cm (6 in), and share a common arrangement of piercing-sucking mouthparts. The name "true bugs" is often limited to the suborder Heteroptera.

The yellow crazy ant, also known as the long-legged ant or Maldive ant, is a species of ant, thought to be native to West Africa or Asia. They have been accidentally introduced to numerous places in the world's tropics.

In ecology, a biological interaction is the effect that a pair of organisms living together in a community have on each other. They can be either of the same species, or of different species. These effects may be short-term, or long-term, both often strongly influence the adaptation and evolution of the species involved. Biological interactions range from mutualism, beneficial to both partners, to competition, harmful to both partners. Interactions can be direct when physical contact is established or indirect, through intermediaries such as shared resources, territories, ecological services, metabolic waste, toxins or growth inhibitors. This type of relationship can be shown by net effect based on individual effects on both organisms arising out of relationship.

Myrmecochory ( ; from Ancient Greek: μύρμηξ, romanized: mýrmēks and χορεία khoreíā is seed dispersal by ants, an ecologically significant ant–plant interaction with worldwide distribution. Most myrmecochorous plants produce seeds with elaiosomes, a term encompassing various external appendages or "food bodies" rich in lipids, amino acids, or other nutrients that are attractive to ants. The seed with its attached elaiosome is collectively known as a diaspore. Seed dispersal by ants is typically accomplished when foraging workers carry diaspores back to the ant colony, after which the elaiosome is removed or fed directly to ant larvae. Once the elaiosome is consumed, the seed is usually discarded in underground middens or ejected from the nest. Although diaspores are seldom distributed far from the parent plant, myrmecochores also benefit from this predominantly mutualistic interaction through dispersal to favourable locations for germination, as well as escape from seed predation.

Vachellia collinsii, previously Acacia collinsii, is a species of flowering plant native to Central America and parts of Africa.

Seed predation, often referred to as granivory, is a type of plant-animal interaction in which granivores feed on the seeds of plants as a main or exclusive food source, in many cases leaving the seeds damaged and not viable. Granivores are found across many families of vertebrates as well as invertebrates ; thus, seed predation occurs in virtually all terrestrial ecosystems. Seed predation is commonly divided into two distinctive temporal categories, pre-dispersal and post-dispersal predation, which affect the fitness of the parental plant and the dispersed offspring, respectively. Mitigating pre- and post-dispersal predation may involve different strategies. To counter seed predation, plants have evolved both physical defenses and chemical defenses. However, as plants have evolved seed defenses, seed predators have adapted to plant defenses. Thus, many interesting examples of coevolution arise from this dynamic relationship.

Myrmecophily is the term applied to positive interspecies associations between ants and a variety of other organisms, such as plants, other arthropods, and fungi. Myrmecophily refers to mutualistic associations with ants, though in its more general use, the term may also refer to commensal or even parasitic interactions.

Trophic cascades are powerful indirect interactions that can control entire ecosystems, occurring when a trophic level in a food web is suppressed. For example, a top-down cascade will occur if predators are effective enough in predation to reduce the abundance, or alter the behavior of their prey, thereby releasing the next lower trophic level from predation.

In ecology, a community is a group or association of populations of two or more different species occupying the same geographical area at the same time, also known as a biocoenosis, biotic community, biological community, ecological community, or life assemblage. The term community has a variety of uses. In its simplest form it refers to groups of organisms in a specific place or time, for example, "the fish community of Lake Ontario before industrialization".

Insect ecology is the interaction of insects, individually or as a community, with the surrounding environment or ecosystem.

Pheidole megacephala is a species of ant in the family Formicidae. It is commonly known as the big-headed ant in the US and the coastal brown ant in Australia. It is a very successful invasive species and is considered a danger to native ants in Australia and other places. It is regarded as one of the world's worst invasive ant species.

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web, often starting with an autotroph, also called a producer, and typically ending at an apex predator, detritivore, or decomposer. It is not the same as a food web. A food chain depicts relations between species based on what they consume for energy in trophic levels, and they are most commonly quantified in length-the number of links between a trophic consumer and the base of the chain.

Structures built by non-human animals, often called animal architecture, are common in many species. Examples of animal structures include termite mounds, ant hills, wasp and beehives, burrow complexes, beaver dams, elaborate nests of birds, and webs of spiders.

Pearl bodies are small, lustrous, pearl-like food bodies produced from the epidermis of leaves, petioles and shoots of certain plants. They are rich in lipids, proteins and carbohydrates, and are sought after by various arthropods and ants, that carry out vigorous protection of the plant against herbivores, thus functioning as a biotic defence. They are globose or club-shaped on short peduncles, easily detached from the plant, and are food sources in the same sense as Beltian bodies, Müllerian bodies, Beccarian bodies, coccid secretions and nectaries. They occur in at least 19 plant families (1982) with tropical and subtropical distribution.

Azteca muelleri is a species of ant in the genus Azteca. Described by the Italian entomologist Carlo Emery in 1893, the species is native to Central and South America. It lives in colonies in the hollow trunk and branches of Cecropia trees. The specific name muelleri was given in honour of a German biologist Fritz Müller, who discovered that the small bodies at the petiole-bases of Cecropia are food bodies.