Principle of Q-switching

Q-switching is achieved by putting some type of variable attenuator inside the laser's optical resonator. When the attenuator is functioning, light which leaves the gain medium does not return, and lasing cannot begin. This attenuation inside the cavity corresponds to a decrease in the Q factor or quality factor of the optical resonator. A high Q factor corresponds to low resonator losses per roundtrip, and vice versa. The variable attenuator is commonly called a "Q-switch", when used for this purpose.

Initially the laser medium is pumped while the Q-switch is set to prevent feedback of light into the gain medium (producing an optical resonator with low Q). This produces a population inversion, but laser operation cannot yet occur since there is no feedback from the resonator. Since the rate of stimulated emission is dependent on the amount of light entering the medium, the amount of energy stored in the gain medium increases as the medium is pumped. Due to losses from spontaneous emission and other processes, after a certain time the stored energy will reach some maximum level; the medium is said to be gain saturated. At this point, the Q-switch device is quickly changed from low to high Q, allowing feedback and the process of optical amplification by stimulated emission to begin. Because of the large amount of energy already stored in the gain medium, the intensity of light in the laser resonator builds up very quickly; this also causes the energy stored in the medium to be depleted almost as quickly. The net result is a short pulse of light output from the laser, known as a giant pulse, which may have a very high peak intensity.

There are two main types of Q-switching:

Active Q-switching

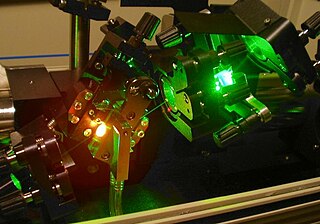

Here, the Q-switch is an externally controlled variable attenuator. This may be a mechanical device such as a shutter, chopper wheel, or spinning mirror/prism placed inside the cavity, or (more commonly) it may be some form of modulator such as an acousto–optic device, a magneto-optic effect device or an electro-optic device – a Pockels cell or Kerr cell. The reduction of losses (increase of Q) is triggered by an external event, typically an electrical signal. The pulse repetition rate can therefore be externally controlled. Modulators generally allow a faster transition from low to high Q, and provide better control. An additional advantage of modulators is that the rejected light may be coupled out of the cavity and can be used for something else. Alternatively, when the modulator is in its low-Q state, an externally generated beam can be coupled into the cavity through the modulator. This can be used to "seed" the cavity with a beam that has desired characteristics (such as transverse mode or wavelength). When the Q is raised, lasing builds up from the initial seed, producing a Q-switched pulse that has characteristics inherited from the seed.

Passive Q-switching

In this case, the Q-switch is a saturable absorber, a material whose transmission increases when the intensity of light exceeds some threshold. The material may be an ion-doped crystal like Cr:YAG, which is used for Q-switching of Nd:YAG lasers, a bleachable dye, or a passive semiconductor device. Initially, the loss of the absorber is high, but still low enough to permit some lasing once a large amount of energy is stored in the gain medium. As the laser power increases, it saturates the absorber, i.e., rapidly reduces the resonator loss, so that the power can increase even faster. Ideally, this brings the absorber into a state with low losses to allow efficient extraction of the stored energy by the laser pulse. After the pulse, the absorber recovers to its high-loss state before the gain recovers, so that the next pulse is delayed until the energy in the gain medium is fully replenished. The pulse repetition rate can only indirectly be controlled, e.g. by varying the laser's pump power and the amount of saturable absorber in the cavity. Direct control of the repetition rate can be achieved by using a pulsed pump source as well as passive Q-switching.

Variants

Jitter can be reduced by not reducing the Q by as much, so that a small amount of light can still circulate in the cavity. This provides a "seed" of light that can aid in the buildup of the next Q-switched pulse.

With cavity dumping, the cavity end mirrors are 100% reflective, so that no output beam is produced when the Q is high. Instead, the Q-switch is used to "dump" the beam out of the cavity after a time delay. The cavity Q goes from low to high to start the laser buildup, and then goes from high to low to "dump" the beam from the cavity all at once. This produces a shorter output pulse than regular Q-switching. Electro-optic modulators are normally used for this, since they can easily be made to function as a near-perfect beam "switch" to couple the beam out of the cavity. The modulator that dumps the beam may be the same modulator that Q-switches the cavity, or a second (possibly identical) modulator. A dumped cavity is more complicated to align than simple Q-switching, and may need a control loop to choose the best time at which to dump the beam from the cavity.

In regenerative amplification, an optical amplifier is placed inside a Q-switched cavity. Pulses of light from another laser (the "master oscillator") are injected into the cavity by lowering the Q to allow the pulse to enter and then increasing the Q to confine the pulse to the cavity where it can be amplified by repeated passes through the gain medium. The pulse is then allowed to leave the cavity via another Q switch.