Defecation follows digestion, and is a necessary process by which organisms eliminate a solid, semisolid, or liquid waste material known as feces from the digestive tract via the anus or cloaca. The act has a variety of names ranging from the common, like pooping or crapping, to the technical, e.g. bowel movement, to the obscene (shitting), to the euphemistic, to the juvenile. The topic, usually avoided in polite company, can become the basis for some potty humor.

Fecal incontinence (FI), or in some forms, encopresis, is a lack of control over defecation, leading to involuntary loss of bowel contents, both liquid stool elements and mucus, or solid feces. When this loss includes flatus (gas), it is referred to as anal incontinence. FI is a sign or a symptom, not a diagnosis. Incontinence can result from different causes and might occur with either constipation or diarrhea. Continence is maintained by several interrelated factors, including the anal sampling mechanism, and incontinence usually results from a deficiency of multiple mechanisms. The most common causes are thought to be immediate or delayed damage from childbirth, complications from prior anorectal surgery, altered bowel habits. An estimated 2.2% of community-dwelling adults are affected. However, reported prevalence figures vary. A prevalence of 8.39% among non-institutionalized U.S adults between 2005 and 2010 has been reported, and among institutionalized elders figures come close to 50%.

An anal fissure is a break or tear in the skin of the anal canal. Anal fissures may be noticed by bright red anal bleeding on toilet paper and undergarments, or sometimes in the toilet. If acute they are painful after defecation, but with chronic fissures, pain intensity often reduces and becomes cyclical.

Hematochezia is a form of blood in stool, in which fresh blood passes through the anus while defecating. It differs from melena, which commonly refers to blood in stool originating from upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). The term derives from Greek αἷμα ("blood") and χέζειν. Hematochezia is commonly associated with lower gastrointestinal bleeding, but may also occur from a brisk upper gastrointestinal bleed. The difference between hematochezia and rectorrhagia is that rectal bleeding is not associated with defecation; instead, it is associated with expulsion of fresh bright red blood without stools. The phrase bright red blood per rectum is associated with hematochezia and rectorrhagia.

A rectal prolapse occurs when walls of the rectum have prolapsed to such a degree that they protrude out of the anus and are visible outside the body. However, most researchers agree that there are 3 to 5 different types of rectal prolapse, depending on whether the prolapsed section is visible externally, and whether the full or only partial thickness of the rectal wall is involved.

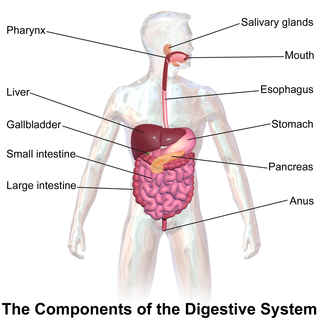

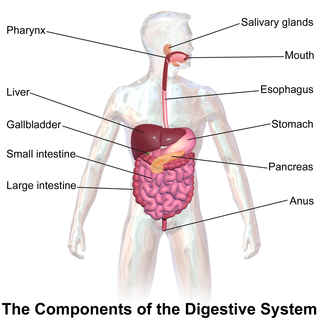

Gastrointestinal diseases refer to diseases involving the gastrointestinal tract, namely the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine and rectum; and the accessory organs of digestion, the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

Rectal tenesmus is a feeling of incomplete defecation. It is the sensation of inability or difficulty to empty the bowel at defecation, even if the bowel contents have already been evacuated. Tenesmus indicates the feeling of a residue, and is not always correlated with the actual presence of residual fecal matter in the rectum. It is frequently painful and may be accompanied by involuntary straining and other gastrointestinal symptoms. Tenesmus has both a nociceptive and a neuropathic component.

Proctitis is an inflammation of the anus and the lining of the rectum, affecting only the last 6 inches of the rectum.

Blood in stool looks different depending on how early it enters the digestive tract—and thus how much digestive action it has been exposed to—and how much there is. The term can refer either to melena, with a black appearance, typically originating from upper gastrointestinal bleeding; or to hematochezia, with a red color, typically originating from lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Evaluation of the blood found in stool depends on its characteristics, in terms of color, quantity and other features, which can point to its source, however, more serious conditions can present with a mixed picture, or with the form of bleeding that is found in another section of the tract. The term "blood in stool" is usually only used to describe visible blood, and not fecal occult blood, which is found only after physical examination and chemical laboratory testing.

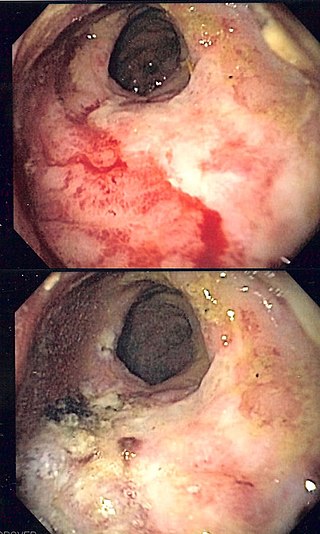

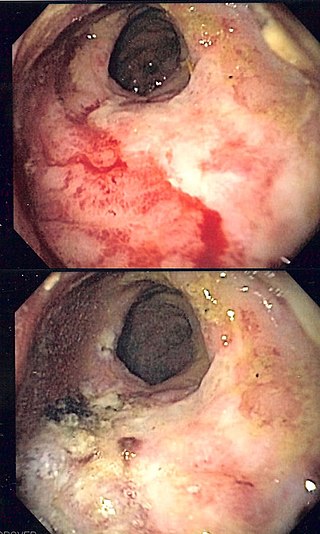

Rectal bleeding refers to bleeding in the rectum, thus a form of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. There are many causes of rectal hemorrhage, including inflamed hemorrhoids, rectal varices, proctitis, stercoral ulcers, and infections. Diagnosis is usually made by proctoscopy, which is an endoscopic test.

Radiation proctitis or radiation proctopathy is a condition characterized by damage to the rectum after exposure to x-rays or other ionizing radiation as a part of radiation therapy. Radiation proctopathy may occur as acute inflammation called "acute radiation proctitis" or with chronic changes characterized by radiation associated vascular ectasiae (RAVE) and chronic radiation proctopathy. Radiation proctitis most commonly occurs after pelvic radiation treatment for cancers such as cervical cancer, prostate cancer, bladder cancer, and rectal cancer. RAVE and chronic radiation proctopathy involves the lower intestine, primarily the sigmoid colon and the rectum, and was previously called chronic radiation proctitis, pelvic radiation disease and radiation enteropathy.

In the anatomy of humans and homologous primates, the descending colon is the part of the colon extending from the left colic flexure to the level of the iliac crest. The function of the descending colon in the digestive system is to store the remains of digested food that will be emptied into the rectum.

Stercoral ulcer is an ulcer of the colon due to pressure and irritation resulting from severe, prolonged constipation due to a large bowel obstruction, damage to the autonomic nervous system, or stercoral colitis. It is most commonly located in the sigmoid colon and rectum. Prolonged constipation leads to production of fecaliths, leading to possible progression into a fecaloma. These hard lumps irritate the rectum and lead to the formation of these ulcers. It results in fresh bleeding per rectum. These ulcers may be seen on imaging, such as a CT scan but are more commonly identified using endoscopy, usually a colonoscopy. Treatment modalities can include both surgical and non-surgical techniques.

Pruritus ani is the irritation of the skin at the exit of the rectum, known as the anus, causing the desire to scratch. The intensity of anal itching increases from moisture, pressure, and rubbing caused by clothing and sitting. At worst, anal itching causes intolerable discomfort that often is accompanied by burning and soreness. It is estimated that up to 5% of the population of the United States experiences this type of discomfort daily.

The rectum is the final straight portion of the large intestine in humans and some other mammals, and the gut in others. The adult human rectum is about 12 centimetres (4.7 in) long, and begins at the rectosigmoid junction at the level of the third sacral vertebra or the sacral promontory depending upon what definition is used. Its diameter is similar to that of the sigmoid colon at its commencement, but it is dilated near its termination, forming the rectal ampulla. It terminates at the level of the anorectal ring or the dentate line, again depending upon which definition is used. In humans, the rectum is followed by the anal canal, which is about 4 centimetres (1.6 in) long, before the gastrointestinal tract terminates at the anal verge. The word rectum comes from the Latin rēctumintestīnum, meaning straight intestine.

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome or SRUS is a chronic, benign disorder of the rectal mucosa. It commonly occurs with varying degrees of rectal prolapse. The condition is thought to be caused by different factors, such as long term constipation, straining during defecation, and dyssynergic defecation. Treatment is by normalization of bowel habits, biofeedback, and other conservative measures. In more severe cases various surgical procedures may be indicated. The condition is relatively rare, affecting approximately 1 in 100,000 people per year. It affects mainly adults aged 30–50. Females are affected slightly more often than males. The disorder can be confused clinically with rectal cancer or other conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, even when a biopsy is done.

Anismus or dyssynergic defecation is the failure of normal relaxation of pelvic floor muscles during attempted defecation. It can occur in both children and adults, and in both men and women. It can be caused by physical defects or it can occur for other reasons or unknown reasons. Anismus that has a behavioral cause could be viewed as having similarities with parcopresis, or psychogenic fecal retention.

Obstructed defecation syndrome is a major cause of functional constipation, of which it is considered a subtype. It is characterized by difficult and/or incomplete emptying of the rectum with or without an actual reduction in the number of bowel movements per week. Normal definitions of functional constipation include infrequent bowel movements and hard stools. In contrast, ODS may occur with frequent bowel movements and even with soft stools, and the colonic transit time may be normal, but delayed in the rectum and sigmoid colon.

In fecal incontinence (FI), surgery may be carried out if conservative measures alone are not sufficient to control symptoms. There are many surgical options described for FI, and they can be considered in 4 general groups.

Neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) is the inability to control defecation due to a deterioration of or injury to the nervous system, resulting in faecal incontinence or constipation. It is common in people with spinal cord injury (SCI), multiple sclerosis (MS) or spina bifida.