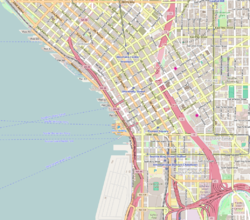

Smith Tower is a skyscraper in the Pioneer Square neighborhood of Seattle, Washington, United States. Completed in 1914, the 38-story, 462 ft (141 m) tower was among the tallest skyscrapers outside New York City at the time of its completion. It was the tallest building west of the Mississippi River until the completion of the Kansas City Power & Light Building in 1931. It remained the tallest building on the U.S. West Coast for nearly half a century, until the Space Needle overtook it in 1962.

Clinton and Russell was a well-known architectural firm founded in 1894 in New York City, United States. The firm was responsible for several New York City buildings, including some in Lower Manhattan.

The Union Trust Building is a commercial building in Seattle, Washington, United States. Located in the city's Pioneer Square neighborhood, on the corner of Main Street and Occidental Way South, it was one of the first rehabilitated buildings in the neighborhood, which is now officially a historic district. In the 1960s, when Pioneer Square was better known as "Skid Road", architect Ralph Anderson purchased the building from investor Sam Israel for $50,000 and set about remodeling it, a project that set a pattern for the next several decades of development in the neighborhood. Anderson also rehabilitated the adjacent Union Trust Annex.

The Grand Opera House in Seattle, Washington, US, designed by Seattle architect Edwin W. Houghton, a leading designer of Pacific Northwest theaters, was once the city's leading theater. Today, only its exterior survives as the shell of a parking garage. Considered by the city's Department of Neighborhoods to be an example of Richardsonian Romanesque, the building stands just outside the northern boundary of the Pioneer Square neighborhood.

The Hoge Building is a 17-story building constructed in 1911 by, and named for James D. Hoge, a banker and real estate investor, on the northwest corner of Second Avenue and Cherry Street in Seattle, Washington. The building was constructed primarily of tan brick and terracotta built over a steel frame in the architectural style of Second Renaissance Revival with elements of Beaux Arts. It was the tallest building in Seattle from 1911 to 1914, until the completion of Smith Tower.

The Alaska Building, which now houses the Courtyard by Marriott Seattle Downtown/Pioneer Square, is a 15-floor building in Seattle, Washington completed in 1904 to designs by St. Louis architects Eames and Young. At the time of its completion, it was the tallest building in the state of Washington—and remained so until the 1910 completion of Spokane's Old National Bank Building.

U.S. Bank Center, formerly U.S. Bank Centre, is a 44-story skyscraper in Seattle, in the U.S. state of Washington. The building opened as Pacific First Centre and was constructed from 1987 to 1989. At 607 feet (185 m), it is currently the eighth-tallest building in Seattle and was designed by Callison Architecture, who is also headquartered in the building. It contains 943,575 sq ft (87,661 m2) of office space.

2nd & Pike, also known as the West Edge Tower, is a 440-foot-tall (130 m) residential skyscraper in Seattle, Washington. The 39-story tower, developed by Urban Visions and designed by Tom Kundig of Olson Kundig Architects, has 339 luxury apartments and several ground-level retail spaces. The 8th floor includes a Medical One primary care clinic.

William Boone was an American architect who practiced mainly in Seattle, Washington from 1882 until 1905. He was one of the founders of the Washington State chapter of the American Institute of Architects as well as its first president. For the majority of the 1880s, he practiced with George Meeker as Boone and Meeker, Seattle's leading architectural firm at the time. In his later years he briefly worked with William H. Willcox as Boone and Willcox and later with James Corner as Boone and Corner. Boone was one of Seattle's most prominent pre-fire architects whose career lasted into the early 20th century outlasting many of his peers. Few of his buildings remain standing today, as many were destroyed in the Great Seattle fire including one of his most well known commissions, the Yesler – Leary Building, built for pioneer Henry Yesler whose mansion Boone also designed. After the fire, he founded the Washington State chapter of the American Institute of Architects and designed the first steel frame office building in Seattle, among several other large brick and public buildings that are still standing in the Pioneer Square district.

The Grand Pacific Hotel is a historic building in Seattle, Washington, United States. It located at 1115-1117 1st Avenue between Spring and Seneca Streets in the city's central business district. The building was designed in July 1889 and constructed in 1890 [Often incorrectly cited as 1898] during the building boom that followed the Great Seattle Fire of 1889. Though designed as an office building, the Grand Central had served as a Single room occupancy hotel nearly since its construction, with the Ye Kenilworth Inn on the upper floors during the 1890s. The hotel was refurnished and reopened in 1900 as the Grand Pacific Hotel, most likely named after the hotel of the same name in Chicago that had just recently been rebuilt. It played a role during the Yukon Gold Rush as one of many hotels that served traveling miners and also housed the offices for the Seattle Woolen Mill, an important outfitter for the Klondike.

The Agen Warehouse, also known as the 1201 Western Building is an historic former warehouse building located at 1201 Western Avenue in Seattle, Washington. Originally constructed in 1910 by John B. Agen (1856–1920), widely considered the father of the dairy industry in the Northwest, for his wholesale dairy commission business, it was designed by the partnership of John Graham, Sr. and David J. Myers with later additions designed by Graham alone. After years of industrial use, the building was fully restored to its present appearance in 1986 for offices and retail with the addition of a penthouse and was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 23, 1998.

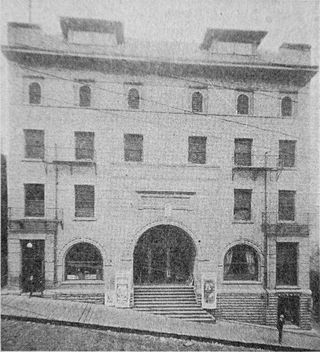

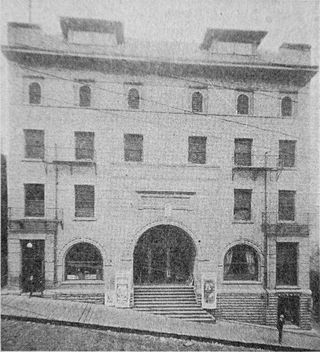

The Barnes Building, originally known as the Odd Fellows' Block, the Masonic Temple from 1909 to 1915, and later Ingram Hall, is a historic fraternal and office building located at 2320-2322 1st Avenue in the Belltown neighborhood of Seattle, Washington. Designed in early 1889 and constructed in late 1890 by Seattle Lodge No. 7 of the International Order of Odd Fellows and designed for use by all of the city's Odd Fellow lodges, it is the earliest known surviving work of Seattle architect William E. Boone and George Meeker and remains in an almost perfect state of preservation. The Barnes building has played an important role in the Belltown Community and Seattle's dance community. It was used by the Odd Fellows for 17 years before their departure to a newer, bigger hall in 1909 and was home to a variety of fraternal & secret societies throughout the early 20th century, with the Free and Accepted Masons being the primary tenant until their own Hall was built in 1915. The ground floor has been a host to a variety of tenants since 1890 ranging from furniture sales to dry goods to farm implement sales and sleeping bag manufacturing, most recently being home to several bars. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places as The Barnes Building on February 24, 1975.

The Fremont Building, also known as the Remsberg Building is a historic commercial building located at 3419 Fremont Avenue North in Seattle, Washington. The two-story building, built in the late 19th and 20th century Revival style, was completed in 1911 and added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 12, 1992. Originally built as a hotel with office space and ground floor retail, the building currently houses offices and retail including an antique mall in the basement.

The Lyon Building is a historic building located at 607 Third Avenue in Downtown Seattle, Washington, United States. It was built in 1910 by the Yukon Investment Company and was named after the city in France of the same name, reflecting the French heritage of the company's owners. It was designed by the firm of Graham & Myers in the Chicago school style of architecture and was built by the Stone & Webster engineering firm, whose use of non-union labor would make the yet unfinished building the target of a bombing by notorious union activist James B. McNamara, who would commit the deadly Los Angeles Times bombing only 1 month after. The Lyon Building was luckily not destroyed due to its substantial construction, and after little delay, it was completed in 1911 and soon became one of Seattle's most popular office addresses for lawyers and judges due to its proximity to Seattle's public safety complex and the King County Courthouse. It was the founding location of many foreign consuls, social and political clubs as well as the City University of Seattle. The building's basement now serves as an entrance the Pioneer Square station of the Seattle Transit Tunnel. The Lyon Building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 30, 1995 and was designated a Seattle landmark on August 16, 1996. In 1997 it was converted to residential use as a shelter and services center for the homeless and at-risk by the non-profit Downtown Emergency Service Center, who are the current owners of the building.

The Colonial Hotel is a historic building in Seattle located at 1119-1123 at the southwest corner of 1st Avenue and Seneca Streets in the city's central business district. The majority of the building recognizable today was constructed in 1901 over a previous building built in 1892-3 that was never completed to its full plans.

The Colonnade Hotel first known as the Stimson Block then later the Standard Hotel, Gateway Hotel and Gatewood Hotel is a historic hotel building in Seattle, Washington located at the Southeast corner of 1st Avenue and Pine Streets in the city's central business district. One of the earliest extant solo projects of architect Charles Bebb, it was built in 1900 by Charles and Fred Stimson, owners of the Stimson lumber mill at Ballard, for use as a hotel. It served that purpose under its various names until the early 1980s and after a brief vacancy was restored into low-income housing by the Plymouth Housing Group. Once owned by the Samis Foundation, it was sold to various LLC owners who would convert it back into a hotel in 2017, currently operating under the name Palihotel. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on August 7, 2007 and became a City of Seattle Landmark in 2017.

The Interurban Building, formerly known as the Seattle National Bank Building (1890–1899), the Pacific Block (1899–1930) and the Smith Tower Annex (1930–1977), is a historic office building located at Yesler Way and Occidental Way S in the Pioneer Square neighborhood of Seattle, Washington, United States. Built from 1890 to 1891 for the then recently formed Seattle National Bank, it is one of the finest examples of Richardsonian Romanesque architecture in the Pacific Northwest and has been cited by local architects as one of the most beautiful buildings in downtown Seattle. It was the breakthrough project of young architect John Parkinson, who would go on to design many notable buildings in the Los Angeles area in the late 19th and early 20th century.

647 Fifth Avenue, originally known as the George W. Vanderbilt Residence, is a commercial building in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It is along the east side of Fifth Avenue between 51st Street and 52nd Street. The building was designed by Hunt & Hunt as one of the "Marble Twins", a pair of houses at 645 and 647 Fifth Avenue. The houses were constructed between 1902 and 1905 as Vanderbilt family residences. Number 645 was occupied by William B. Osgood Field, while number 647 was owned by George W. Vanderbilt and rented to Robert Wilson Goelet; both were part of the Vanderbilt family by marriage.

The Mutual Life Building, originally known as the Yesler Building, is an historic office building located in Seattle's Pioneer Square neighborhood that anchors the West side of the square. The building sits on one of the most historic sites in the city; the original location of Henry Yesler's cookhouse that served his sawmill in the early 1850s and was one of Seattle's first community gathering spaces. It was also the site of the first sermon delivered and first lawsuit tried in King County. By the late 1880s Yesler had replaced the old shanties with several substantial brick buildings including the grand Yesler-Leary Building, which would all be destroyed by the Great Seattle Fire in 1889. The realignment of First Avenue to reconcile Seattle's clashing street grids immediately after the fire would split Yesler's corner into two pieces; the severed eastern corner would become part of Pioneer Square park, and on the western lot Yesler would begin construction of his eponymous block in 1890 to house the First National Bank, which had previously been located in the Yesler-Leary Building. Portland brewer Louis Feurer began construction of a conjoined building to the west of Yesler's at the same time. Progress of both would be stunted and the original plans of architect Elmer H. Fisher were dropped by the time construction resumed in 1892. It would take 4 phases and 4 different architects before the building reached its final form in 1905. The Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York only owned the building from 1896 to 1909, but it would retain their name even after the company moved out in 1916.

The Schoenfeld Building, also known as the Standard Block, the Struve Building and the Meves Building, is a historic commercial building located at 1012 1st Avenue in downtown Seattle, Washington. Originally built in 1891 by land real estate and interurban developer Fred E. Sander, it has been used for retail, light manufacturing, and office space. It was expanded and remodeled to its current appearance in the late 1890s by one of its most notable tenants, Louis Schoenfeld, to house his rapidly expanding Standard Furniture Company which in less than a decade would outgrow this and a now-demolished neighboring building and result in the construction of the Broadacres Building at 2nd and Pine streets in 1907.