Pharmacology is the science of drugs and medications, including a substance's origin, composition, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, therapeutic use, and toxicology. More specifically, it is the study of the interactions that occur between a living organism and chemicals that affect normal or abnormal biochemical function. If substances have medicinal properties, they are considered pharmaceuticals.

Cannabinoids are several structural classes of compounds found in the cannabis plant primarily and most animal organisms or as synthetic compounds. The most notable cannabinoid is the phytocannabinoid tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (delta-9-THC), the primary psychoactive compound in cannabis. Cannabidiol (CBD) is also a major constituent of temperate cannabis plants and a minor constituent in tropical varieties. At least 100 distinct phytocannabinoids have been isolated from cannabis, although only four have been demonstrated to have a biogenetic origin. It was reported in 2020 that phytocannabinoids can be found in other plants such as rhododendron, licorice and liverwort, and earlier in Echinacea.

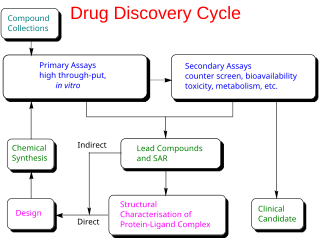

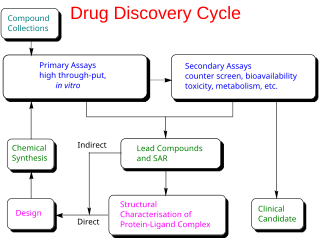

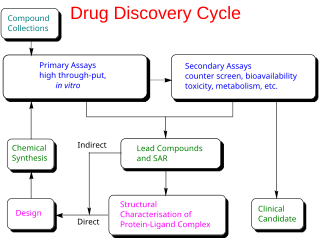

In the fields of medicine, biotechnology, and pharmacology, drug discovery is the process by which new candidate medications are discovered.

Drug design, often referred to as rational drug design or simply rational design, is the inventive process of finding new medications based on the knowledge of a biological target. The drug is most commonly an organic small molecule that activates or inhibits the function of a biomolecule such as a protein, which in turn results in a therapeutic benefit to the patient. In the most basic sense, drug design involves the design of molecules that are complementary in shape and charge to the biomolecular target with which they interact and therefore will bind to it. Drug design frequently but not necessarily relies on computer modeling techniques. This type of modeling is sometimes referred to as computer-aided drug design. Finally, drug design that relies on the knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of the biomolecular target is known as structure-based drug design. In addition to small molecules, biopharmaceuticals including peptides and especially therapeutic antibodies are an increasingly important class of drugs and computational methods for improving the affinity, selectivity, and stability of these protein-based therapeutics have also been developed.

A receptor antagonist is a type of receptor ligand or drug that blocks or dampens a biological response by binding to and blocking a receptor rather than activating it like an agonist. Antagonist drugs interfere in the natural operation of receptor proteins. They are sometimes called blockers; examples include alpha blockers, beta blockers, and calcium channel blockers. In pharmacology, antagonists have affinity but no efficacy for their cognate receptors, and binding will disrupt the interaction and inhibit the function of an agonist or inverse agonist at receptors. Antagonists mediate their effects by binding to the active site or to the allosteric site on a receptor, or they may interact at unique binding sites not normally involved in the biological regulation of the receptor's activity. Antagonist activity may be reversible or irreversible depending on the longevity of the antagonist–receptor complex, which, in turn, depends on the nature of antagonist–receptor binding. The majority of drug antagonists achieve their potency by competing with endogenous ligands or substrates at structurally defined binding sites on receptors.

High-throughput screening (HTS) is a method for scientific discovery especially used in drug discovery and relevant to the fields of biology, materials science and chemistry. Using robotics, data processing/control software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors, high-throughput screening allows a researcher to quickly conduct millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests. Through this process one can quickly recognize active compounds, antibodies, or genes that modulate a particular biomolecular pathway. The results of these experiments provide starting points for drug design and for understanding the noninteraction or role of a particular location.

A biological target is anything within a living organism to which some other entity is directed and/or binds, resulting in a change in its behavior or function. Examples of common classes of biological targets are proteins and nucleic acids. The definition is context-dependent, and can refer to the biological target of a pharmacologically active drug compound, the receptor target of a hormone, or some other target of an external stimulus. Biological targets are most commonly proteins such as enzymes, ion channels, and receptors.

Pharmacotherapy, also known as pharmacological therapy or drug therapy, is defined as medical treatment that utilizes one or more pharmaceutical drugs to improve ongoing symptoms, treat the underlying condition, or act as a prevention for other diseases (prophylaxis).

In pharmacology, the term mechanism of action (MOA) refers to the specific biochemical interaction through which a drug substance produces its pharmacological effect. A mechanism of action usually includes mention of the specific molecular targets to which the drug binds, such as an enzyme or receptor. Receptor sites have specific affinities for drugs based on the chemical structure of the drug, as well as the specific action that occurs there.

Chemogenomics, or chemical genomics, is the systematic screening of targeted chemical libraries of small molecules against individual drug target families with the ultimate goal of identification of novel drugs and drug targets. Typically some members of a target library have been well characterized where both the function has been determined and compounds that modulate the function of those targets have been identified. Other members of the target family may have unknown function with no known ligands and hence are classified as orphan receptors. By identifying screening hits that modulate the activity of the less well characterized members of the target family, the function of these novel targets can be elucidated. Furthermore, the hits for these targets can be used as a starting point for drug discovery. The completion of the human genome project has provided an abundance of potential targets for therapeutic intervention. Chemogenomics strives to study the intersection of all possible drugs on all of these potential targets.

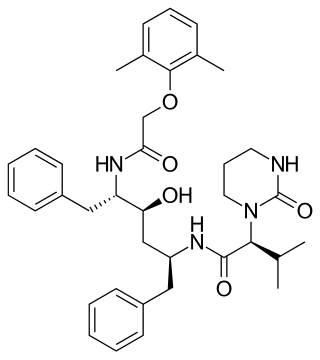

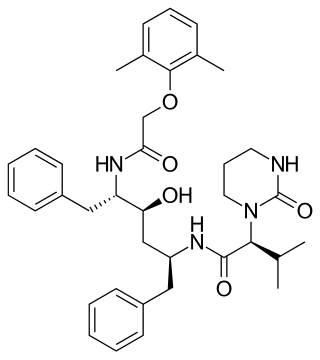

Lopinavir is an antiretroviral of the protease inhibitor class. It is used against HIV infections as a fixed-dose combination with another protease inhibitor, ritonavir (lopinavir/ritonavir).

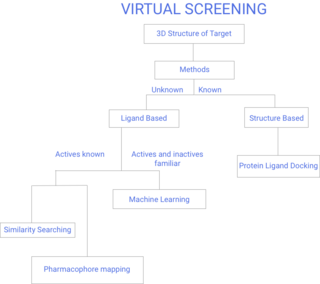

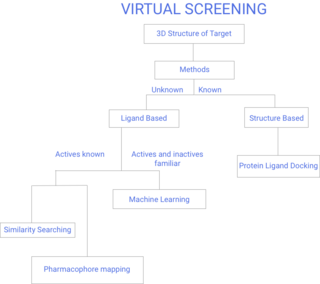

Virtual screening (VS) is a computational technique used in drug discovery to search libraries of small molecules in order to identify those structures which are most likely to bind to a drug target, typically a protein receptor or enzyme.

In the field of molecular biology, the pregnane X receptor (PXR), also known as the steroid and xenobiotic sensing nuclear receptor (SXR) or nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group I, member 2 (NR1I2) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the NR1I2 gene.

Druglikeness is a qualitative concept used in drug design for how "druglike" a substance is with respect to factors like bioavailability. It is estimated from the molecular structure before the substance is even synthesized and tested. A druglike molecule has properties such as:

High throughput biology is the use of automation equipment with classical cell biology techniques to address biological questions that are otherwise unattainable using conventional methods. It may incorporate techniques from optics, chemistry, biology or image analysis to permit rapid, highly parallel research into how cells function, interact with each other and how pathogens exploit them in disease.

Fragment-based lead discovery (FBLD) also known as fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) is a method used for finding lead compounds as part of the drug discovery process. Fragments are small organic molecules which are small in size and low in molecular weight. It is based on identifying small chemical fragments, which may bind only weakly to the biological target, and then growing them or combining them to produce a lead with a higher affinity. FBLD can be compared with high-throughput screening (HTS). In HTS, libraries with up to millions of compounds, with molecular weights of around 500 Da, are screened, and nanomolar binding affinities are sought. In contrast, in the early phase of FBLD, libraries with a few thousand compounds with molecular weights of around 200 Da may be screened, and millimolar affinities can be considered useful. FBLD is a technique being used in research for discovering novel potent inhibitors. This methodology could help to design multitarget drugs for multiple diseases. The multitarget inhibitor approach is based on designing an inhibitor for the multiple targets. This type of drug design opens up new polypharmacological avenues for discovering innovative and effective therapies. Neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s, among others, also show rather complex etiopathologies. Multitarget inhibitors are more appropriate for addressing the complexity of AD and may provide new drugs for controlling the multifactorial nature of AD, stopping its progression.

Phenotypic screening is a type of screening used in biological research and drug discovery to identify substances such as small molecules, peptides, or RNAi that alter the phenotype of a cell or an organism in a desired manner. Phenotypic screening must be followed up with identification and validation, often through the use of chemoproteomics, to identify the mechanisms through which a phenotypic hit works.

Chemical genetics is the investigation of the function of proteins and signal transduction pathways in cells by the screening of chemical libraries of small molecules. Chemical genetics is analogous to classical genetic screen where random mutations are introduced in organisms, the phenotype of these mutants is observed, and finally the specific gene mutation (genotype) that produced that phenotype is identified. In chemical genetics, the phenotype is disturbed not by introduction of mutations, but by exposure to small molecule tool compounds. Phenotypic screening of chemical libraries is used to identify drug targets or to validate those targets in experimental models of disease. Recent applications of this topic have been implicated in signal transduction, which may play a role in discovering new cancer treatments. Chemical genetics can serve as a unifying study between chemistry and biology. The approach was first proposed by Tim Mitchison in 1994 in an opinion piece in the journal Chemistry & Biology entitled "Towards a pharmacological genetics".

In the field of drug discovery, classical pharmacology, also known as forward pharmacology, or phenotypic drug discovery (PDD), relies on phenotypic screening of chemical libraries of synthetic small molecules, natural products or extracts to identify substances that have a desirable therapeutic effect. Using the techniques of medicinal chemistry, the potency, selectivity, and other properties of these screening hits are optimized to produce candidate drugs.

Chemoproteomics entails a broad array of techniques used to identify and interrogate protein-small molecule interactions. Chemoproteomics complements phenotypic drug discovery, a paradigm that aims to discover lead compounds on the basis of alleviating a disease phenotype, as opposed to target-based drug discovery, in which lead compounds are designed to interact with predetermined disease-driving biological targets. As phenotypic drug discovery assays do not provide confirmation of a compound's mechanism of action, chemoproteomics provides valuable follow-up strategies to narrow down potential targets and eventually validate a molecule's mechanism of action. Chemoproteomics also attempts to address the inherent challenge of drug promiscuity in small molecule drug discovery by analyzing protein-small molecule interactions on a proteome-wide scale. A major goal of chemoproteomics is to characterize the interactome of drug candidates to gain insight into mechanisms of off-target toxicity and polypharmacology.