Voltage ripple

A non-ideal DC voltage waveform can be viewed as a composite of a constant DC component (offset) with an alternating (AC) voltage—the ripple voltage—overlaid. The ripple component is often small in magnitude relative to the DC component, but in absolute terms, ripple (as in the case of HVDC transmission systems) may be thousands of volts. Ripple itself is a composite (non-sinusoidal) waveform consisting of harmonics of some fundamental frequency which is usually the original AC line frequency, but in the case of switched-mode power supplies, the fundamental frequency can be tens of kilohertz to megahertz. The characteristics and components of ripple depend on its source: there is single-phase half- and full-wave rectification, and three-phase half- and full-wave rectification. Rectification can be controlled (uses Silicon Controlled Rectifiers (SCRs)) or uncontrolled (uses diodes). There is in addition, active rectification which uses transistors.

Various properties of ripple voltage may be important depending on application: the equation of the ripple for Fourier analysis to determine the constituent harmonics; the peak (usually peak-to-peak) value of the voltage; the root mean square (RMS) value of the voltage which is a component of power transmitted; the ripple factor γ, the ratio of RMS value to DC voltage output; the conversion ratio (also called the rectification ratio or "efficiency") η, the ratio of DC output power to AC input power; and form-factor, the ratio of the RMS value of the output voltage to the average value of the output voltage. Analogous ratios for output ripple current may also be computed.

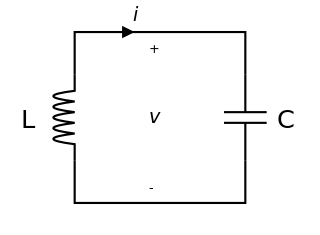

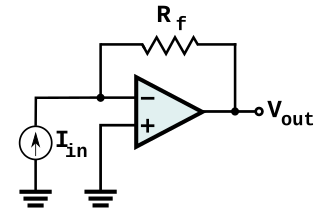

An electronic filter with high impedance at the ripple frequency may be used to reduce ripple voltage and increase or decrease DC output; such a filter is often called a smoothing filter.

The initial step in AC to DC conversion is to send the AC current through a rectifier. The ripple voltage output is very large in this situation; the peak-to-peak ripple voltage is equal to the peak AC voltage minus the forward voltage of the rectifier diodes. In the case of an SS silicon diode, the forward voltage is 0.7 V; for vacuum tube rectifiers, forward voltage usually ranges between 25 and 67 V (5R4). The output voltage is a sine wave with the negative half-cycles inverted. The equation is:

The Fourier expansion of the function is:

Several relevant properties are apparent on inspection of the Fourier series:

- the constant (largest) term must be the DC voltage

- the fundamental (line frequency) is not present

- the expansion consists of only even harmonics of the fundamental

- the amplitude of the harmonics is proportional to where is the order of the harmonic

- the term for the second-order harmonic is often used to represent the entire ripple voltage to simplify computation

The output voltages are:

where

- is the time-varying voltage across the load, for period 0 to T

- is the period of , may be taken as radians

The ripple factor is:

The form factor is:

The peak factor is:

The conversion ratio is:

The transformer utilization factor is:

Filtering

This section is missing information about T (LCL) and series resonant choke (CL) input filter topologies.(November 2017) |

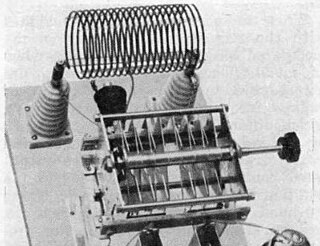

Reducing ripple is only one of several principal considerations in power supply filter design. [nb 1] The filtering of ripple voltage is analogous to filtering other kinds of signals. However, in AC/DC power conversion as well as DC power generation, high voltages and currents or both may be output as ripple. Therefore, large discrete components like high ripple-current rated electrolytic capacitors, large iron-core chokes and wire-wound power resistors are best suited to reduce ripple to manageable proportions before passing the current to an IC component like a voltage regulator, or on to the load. The kind of filtering required depends on the amplitude of the various harmonics of the ripple and the demands of the load. For example, a moving coil (MC) input circuit of a phono preamplifier may require that ripple be reduced to no more than a few hundred nanovolts (10−9V). In contrast, a battery charger, being a wholly resistive circuit, does not require any ripple filtering. Since the desired output is direct current (essentially 0 Hz), ripple filters are usually configured as low pass filters characterized by shunt capacitors and series chokes. Series resistors may replace chokes for reducing the output DC voltage, and shunt resistors may be used for voltage regulation.