Mali is located in Africa. The history of the territory of modern Mali may be divided into:

North Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of the Western Sahara in the west, to Egypt and Sudan's Red Sea coast in the east.

The Sahara desert, as defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), includes the hyper-arid center of the Sahara, between latitudes 18° N and 30° N. It is one of several desert and xeric shrubland ecoregions that cover the northern portion of the African continent.

The prehistory of North Africa spans the period of earliest human presence in the region to gradual onset of historicity in the Maghreb during classical antiquity. Early anatomically modern humans are known to have been present at Jebel Irhoud, in what is now Morocco, approximately 300,000 years ago. The Nile Valley region, via ancient Egypt, contributed to the Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age periods of the Old World, along with the ancient Near East.

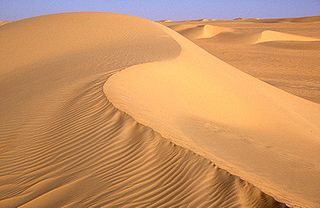

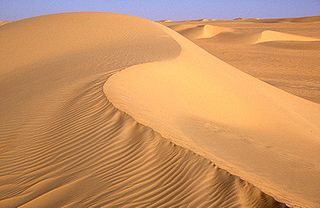

The Sahara is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of 9,200,000 square kilometres (3,600,000 sq mi), it is the largest hot desert in the world and the third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Arctic.

A pluvial lake is a body of water that accumulated in a basin because of a greater moisture availability resulting from changes in temperature and/or precipitation. These intervals of greater moisture availability are not always contemporaneous with glacial periods. Pluvial lakes are typically closed lakes that occupied endorheic basins. Pluvial lakes that have since evaporated and dried out may also be referred to as paleolakes.

Aeolian processes, also spelled eolian, pertain to wind activity in the study of geology and weather and specifically to the wind's ability to shape the surface of the Earth. Winds may erode, transport, and deposit materials and are effective agents in regions with sparse vegetation, a lack of soil moisture and a large supply of unconsolidated sediments. Although water is a much more powerful eroding force than wind, aeolian processes are important in arid environments such as deserts.

The Upper Paleolithic is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago, according to some theories coinciding with the appearance of behavioral modernity in early modern humans, until the advent of the Neolithic Revolution and agriculture.

The Ténéré is a desert region in south central Sahara. It comprises a vast plain of sand stretching from northeastern Niger to western Chad, occupying an area of over 400,000 square kilometres (150,000 sq mi). The Ténéré's boundaries are said to be the Aïr Mountains in the west, the Hoggar Mountains in the north, the Djado Plateau in the northeast, the Tibesti Mountains in the east, and the basin of Lake Chad in the south. The central part of the desert, the Erg du Bilma, is centred at approximately 17°35′N10°55′E. It is the locus of the Neolithic Tenerian culture.

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as the Upper Pleistocene from a stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. It is currently defined as the time between c. 129,000 and c. 11,700 years ago. The late Pleistocene equates to the proposed Tarantian Age of the geologic time scale, preceded by the officially ratified Chibanian. The beginning of the Late Pleistocene is the transition between the end of the Penultimate Glacial Period and the beginning of the Last Interglacial around 130,000 years ago. The Late Pleistocene ends with the termination of the Younger Dryas, some 11,700 years ago when the Holocene Epoch began.

The 4.2-kiloyear BP aridification event, also known as the 4.2 ka event, was one of the most severe climatic events of the Holocene epoch. It defines the beginning of the current Meghalayan age in the Holocene epoch.

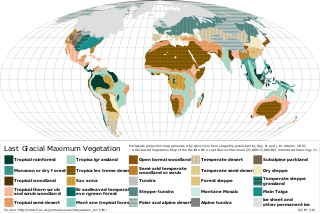

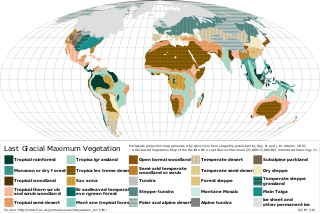

Last Glacial Maximum refugia were places (refugia) in which humans and other species survived during the Last Glacial Period, around 25,000 to 18,000 years ago. Glacial refugia are areas that climate changes were not as severe, and where species could recolonize after deglaciation.

The climate of Mount Kenya has played a critical role in the development of the mountain, influencing the topography and ecology amongst other factors. The area around Mount Kenya is covered by a comparably large number of weather station data with long measurements series and thus the climate is well recorded. It has a typical equatorial mountain climate which Hedberg described as winter every night and summer every day.

The Mousterian Pluvial is a mostly obsolete term for a prehistoric wet and rainy (pluvial) period in North Africa. It was described as beginning around 50,000 years before the present (BP), lasting roughly 20,000 years, and ending ca. 30,000 BP.

The Abbassia Pluvial was an extended wet and rainy period in the climate history of North Africa, lasting from c. 120,000 to 90,000 years ago. As such it spans the transitional period connecting the Lower and Middle Paleolithic.

The South Saharan steppe and woodlands, also known as the South Sahara desert, is a deserts and xeric shrublands ecoregion of northern Africa. This band is a transitional region between the Sahara's very arid center to the north, and the wetter Sahelian Acacia savanna ecoregion to the south. In pre-modern times, the grasslands were grazed by migratory gazelles and other ungulates after the rainfalls. More recently, over-grazing by domestic livestock have degraded the territory. Despite the name of the ecoregion, there are few 'woodlands' in the area; those that exist are generally acacia and shrubs along rivers and in wadis.

This timeline of prehistory covers the time from the appearance of Homo sapiens approximately 315,000 years ago in Africa to the invention of writing, over 5,000 years ago, with the earliest records going back to 3,200 BC. Prehistory covers the time from the Paleolithic to the beginning of ancient history.

North African climate cycles have a unique history that can be traced back millions of years. The cyclic climate pattern of the Sahara is characterized by significant shifts in the strength of the North African Monsoon. When the North African Monsoon is at its strongest, annual precipitation and consequently vegetation in the Sahara region increase, resulting in conditions commonly referred to as the "green Sahara". For a relatively weak North African Monsoon, the opposite is true, with decreased annual precipitation and less vegetation resulting in a phase of the Sahara climate cycle known as the "desert Sahara".

The African humid period is a climate period in Africa during the late Pleistocene and Holocene geologic epochs, when northern Africa was wetter than today. The covering of much of the Sahara desert by grasses, trees and lakes was caused by changes in the Earth's axial tilt; changes in vegetation and dust in the Sahara which strengthened the African monsoon; and increased greenhouse gases. During the preceding Last Glacial Maximum, the Sahara contained extensive dune fields and was mostly uninhabited. It was much larger than today, and its lakes and rivers such as Lake Victoria and the White Nile were either dry or at low levels. The humid period began about 14,600–14,500 years ago at the end of Heinrich event 1, simultaneously to the Bølling–Allerød warming. Rivers and lakes such as Lake Chad formed or expanded, glaciers grew on Mount Kilimanjaro and the Sahara retreated. Two major dry fluctuations occurred; during the Younger Dryas and the short 8.2 kiloyear event. The African humid period ended 6,000–5,000 years ago during the Piora Oscillation cold period. While some evidence points to an end 5,500 years ago, in the Sahel, Arabia and East Africa, the end of the period appears to have taken place in several steps, such as the 4.2-kiloyear event.

Mundafan was a former lake in Saudi Arabia, within presently desert-like areas. It formed during the Pleistocene and Holocene, when orbitally mediated changes in climate increased monsoon precipitation in the peninsula, allowing runoff to form a lake with a maximum area of 300 square kilometres (120 sq mi). It was populated by fishes and surrounded by reeds and savanna, which supported human populations.