An illusion is a distortion of the senses, which can reveal how the mind normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. Although illusions distort our perception of reality, they are generally shared by most people.

Within visual perception, an optical illusion is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide variety; their categorization is difficult because the underlying cause is often not clear but a classification proposed by Richard Gregory is useful as an orientation. According to that, there are three main classes: physical, physiological, and cognitive illusions, and in each class there are four kinds: Ambiguities, distortions, paradoxes, and fictions. A classical example for a physical distortion would be the apparent bending of a stick half immerged in water; an example for a physiological paradox is the motion aftereffect. An example for a physiological fiction is an afterimage. Three typical cognitive distortions are the Ponzo, Poggendorff, and Müller-Lyer illusion. Physical illusions are caused by the physical environment, e.g. by the optical properties of water. Physiological illusions arise in the eye or the visual pathway, e.g. from the effects of excessive stimulation of a specific receptor type. Cognitive visual illusions are the result of unconscious inferences and are perhaps those most widely known.

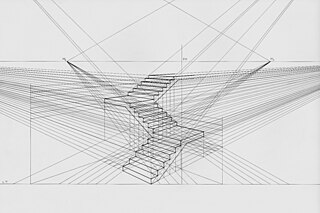

An impossible object is a type of optical illusion that consists of a two-dimensional figure which is instantly and naturally understood by the retina as representing a projection of a three-dimensional object.

Auditory illusions are false perceptions of a real sound or outside stimulus. These false perceptions are the equivalent of an optical illusion: the listener hears either sounds which are not present in the stimulus, or sounds that should not be possible given the circumstance on how they were created.

The Müller-Lyer illusion is an optical illusion consisting of three stylized arrows. When viewers are asked to place a mark on the figure at the midpoint, they tend to place it more towards the "tail" end. The illusion was devised by Franz Carl Müller-Lyer (1857–1916), a German sociologist, in 1889.

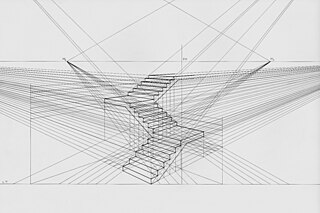

Linear or point-projection perspective is one of two types of graphical projection perspective in the graphic arts; the other is parallel projection. Linear perspective is an approximate representation, generally on a flat surface, of an image as it is seen by the eye. The most characteristic features of linear perspective are that objects appear smaller as their distance from the observer increases, and that they are subject to foreshortening, meaning that an object's dimensions along the line of sight appear shorter than its dimensions across the line of sight. All objects will recede to points in the distance, usually along the horizon line, but also above and below the horizon line depending on the view used.

The McGurk effect is a perceptual phenomenon that demonstrates an interaction between hearing and vision in speech perception. The illusion occurs when the auditory component of one sound is paired with the visual component of another sound, leading to the perception of a third sound. The visual information a person gets from seeing a person speak changes the way they hear the sound. If a person is getting poor quality auditory information but good quality visual information, they may be more likely to experience the McGurk effect. Integration abilities for audio and visual information may also influence whether a person will experience the effect. People who are better at sensory integration have been shown to be more susceptible to the effect. Many people are affected differently by the McGurk effect based on many factors, including brain damage and other disorders.

The year 1990 in science and technology involved some significant events.

The term composition means "putting together". It can be thought of as the organization of the elements of art according to the principles of art. Composition can apply to any work of art, from music through writing and into photography, that is arranged using conscious thought.

The Ponzo illusion is a geometrical-optical illusion that was first demonstrated by the Italian psychologist Mario Ponzo (1882–1960) in 1911. He suggested that the human mind judges an object's size based on its background. He showed this by drawing two identical lines across a pair of converging lines, similar to railway tracks. The upper line looks longer because we interpret the converging sides according to linear perspective as parallel lines receding into the distance. In this context, we interpret the upper line as though it were farther away, so we see it as longer – a farther object would have to be longer than a nearer one for both to produce retinal images of the same size.

The Jastrow illusion is an optical illusion attributed to the Polish-American psychologist Joseph Jastrow. This optical illusion is known under different names: Ring-Segment illusion, Jastrow illusion, Wundt area illusion or Wundt-Jastrow illusion.

Subjective constancy or perceptual constancy is the perception of an object or quality as constant even though our sensation of the object changes. While the physical characteristics of an object may not change, in an attempt to deal with the external world, the human perceptual system has mechanisms that adjust to the stimulus.

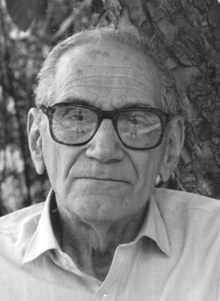

Roger Newland Shepard is an American cognitive scientist and author of the "universal law of generalization" (1987). He is considered a father of research on spatial relations. He studied mental rotation, and was an inventor of non-metric multidimensional scaling, a method for representing certain kinds of statistical data in a graphical form that can be apprehended by humans. The optical illusion called Shepard tables and the auditory illusion called Shepard tones are named for him.

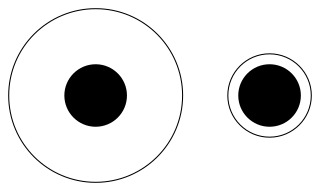

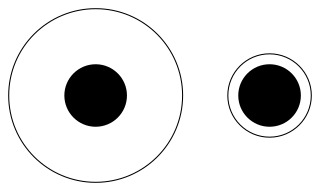

The Ebbinghaus illusion or Titchener circles is an optical illusion of relative size perception. Named for its discoverer, the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850–1909), the illusion was popularized in the English-speaking world by Edward B. Titchener in a 1901 textbook of experimental psychology, hence its alternative name. In the best-known version of the illusion, two circles of identical size are placed near to each other, and one is surrounded by large circles while the other is surrounded by small circles. As a result of the juxtaposition of circles, the central circle surrounded by large circles appears smaller than the central circle surrounded by small circles.

In visual perception, the kinetic depth effect refers to the phenomenon whereby the three-dimensional structural form of an object can be perceived when the object is moving. In the absence of other visual depth cues, this might be the only perception mechanism available to infer the object's shape. Being able to identify a structure from a motion stimulus through the human visual system was shown by Wallach and O'Connell in the 1950s through their experiments.

The Delboeuf illusion is an optical illusion of relative size perception: In the best-known version of the illusion, two discs of identical size have been placed near to each other and one is surrounded by a ring; the surrounded disc then appears larger than the non-surrounded disc if the ring is close, while appearing smaller than the non-surrounded disc if the ring is distant. A 2005 study suggests it is caused by the same visual processes that cause the Ebbinghaus illusion.

Geometrical-optical illusions are visual illusions, also optical illusions, in which the geometrical properties of what is seen differ from those of the corresponding objects in the visual field.

Hans Wallach was a German-American experimental psychologist whose research focused on perception and learning. Although he was trained in the Gestalt psychology tradition, much of his later work explored the adaptability of perceptual systems based on the perceiver's experience, whereas most Gestalt theorists emphasized inherent qualities of stimuli and downplayed the role of experience. Wallach's studies of achromatic surface color laid the groundwork for subsequent theories of lightness constancy, and his work on sound localization elucidated the perceptual processing that underlies stereophonic sound. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, a Guggenheim Fellow, and recipient of the Howard Crosby Warren Medal of the Society of Experimental Psychologists.

Ptolemy's Optics is a 2nd-century book on geometrical optics, dealing with reflection, refraction, and colour. The book was most likely written late in Ptolemy's life, after the Almagest, during the 160s. The work is of great importance in the early history of optics. The Greek text has been lost completely. Fragments of the work survive only in the form of a Latin translation, prepared around 1154 by one Admiral Eugene of Sicily based on an Arabic translation which was presumably based on the Greek original. Both the Arabic and the Greek texts are lost entirely, and the Latin text is "badly mangled". The Latin text was edited by Lejeune (1956). The English translation by Smith (1996) is based on Lejeune's Latin text.

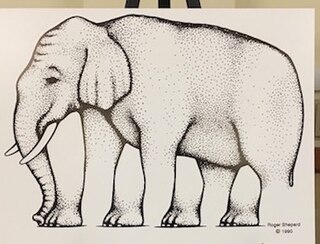

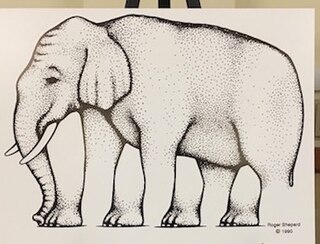

The Shepard elephant, also known as L'egs-istential Quandary or the impossible elephant is an optical illusion, of the type impossible object, based on figure-ground confusion. As its creator Roger Shepard explains:

The elephant…belongs to a class of objects that are truly impossible in that the object itself cannot be globally segregated from the nonobject or background. Parts of the object become the background, and vice versa.