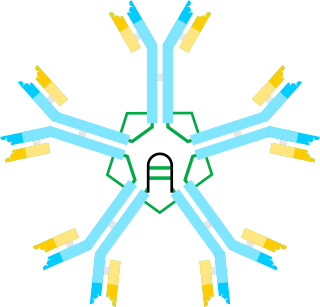

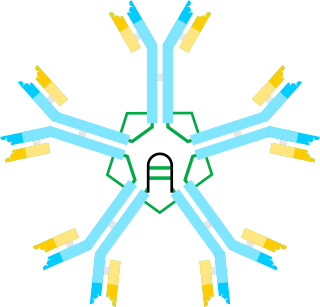

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that cause disease. Antibodies can recognize virtually any size antigen with diverse chemical compositions from molecules. Each antibody recognizes one or more specific antigens. Antigen literally means "antibody generator", as it is the presence of an antigen that drives the formation of an antigen-specific antibody. Each tip of the "Y" of an antibody contains a paratope that specifically binds to one particular epitope on an antigen, allowing the two molecules to bind together with precision. Using this mechanism, antibodies can effectively "tag" a microbe or an infected cell for attack by other parts of the immune system, or can neutralize it directly.

B cells, also known as B lymphocytes, are a type of white blood cell of the lymphocyte subtype. They function in the humoral immunity component of the adaptive immune system. B cells produce antibody molecules which may be either secreted or inserted into the plasma membrane where they serve as a part of B-cell receptors. When a naïve or memory B cell is activated by an antigen, it proliferates and differentiates into an antibody-secreting effector cell, known as a plasmablast or plasma cell. In addition, B cells present antigens and secrete cytokines. In mammals B cells mature in the bone marrow, which is at the core of most bones. In birds, B cells mature in the bursa of Fabricius, a lymphoid organ where they were first discovered by Chang and Glick, which is why the B stands for bursa and not bone marrow, as commonly believed.

In immunology, a memory B cell (MBC) is a type of B lymphocyte that forms part of the adaptive immune system. These cells develop within germinal centers of the secondary lymphoid organs. Memory B cells circulate in the blood stream in a quiescent state, sometimes for decades. Their function is to memorize the characteristics of the antigen that activated their parent B cell during initial infection such that if the memory B cell later encounters the same antigen, it triggers an accelerated and robust secondary immune response. Memory B cells have B cell receptors (BCRs) on their cell membrane, identical to the one on their parent cell, that allow them to recognize antigen and mount a specific antibody response.

The adaptive immune system, also known as the acquired immune system, or specific immune system is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate pathogens or prevent their growth. The acquired immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies found in vertebrates.

In immunology, affinity maturation is the process by which TFH cell-activated B cells produce antibodies with increased affinity for antigen during the course of an immune response. With repeated exposures to the same antigen, a host will produce antibodies of successively greater affinities. A secondary response can elicit antibodies with several fold greater affinity than in a primary response. Affinity maturation primarily occurs on membrane immunoglobulin of germinal center B cells and as a direct result of somatic hypermutation (SHM) and selection by TFH cells.

Activation-induced cytidine deaminase, also known as AICDA, AID and single-stranded DNA cytosine deaminase, is a 24 kDa enzyme which in humans is encoded by the AICDA gene. It creates mutations in DNA by deamination of cytosine base, which turns it into uracil. In other words, it changes a C:G base pair into a U:G mismatch. The cell's DNA replication machinery recognizes the U as a T, and hence C:G is converted to a T:A base pair. During germinal center development of B lymphocytes, error-prone DNA repair following AID action also generates other types of mutations, such as C:G to A:T. AID is a member of the APOBEC family.

Hypergammaglobulinemia is a medical condition with elevated levels of gamma globulin. It is a type of immunoproliferative disorder.

Germinal centers or germinal centres (GCs) are transiently formed structures within B cell zone (follicles) in secondary lymphoid organs – lymph nodes, ileal Peyer's patches, and the spleen – where mature B cells are activated, proliferate, differentiate, and mutate their antibody genes during a normal immune response; most of the germinal center B cells (BGC) are removed by tingible body macrophages. There are several key differences between naive B cells and GC B cells, including level of proliferative activity, size, metabolic activity and energy production. The B cells develop dynamically after the activation of follicular B cells by T-dependent antigen. The initiation of germinal center formation involves the interaction between B and T cells in the interfollicular area of the lymph node, CD40-CD40L ligation, NF-kB signaling and expression of IRF4 and BCL6.

V(D)J recombination is the mechanism of somatic recombination that occurs only in developing lymphocytes during the early stages of T and B cell maturation. It results in the highly diverse repertoire of antibodies/immunoglobulins and T cell receptors (TCRs) found in B cells and T cells, respectively. The process is a defining feature of the adaptive immune system.

The fifth type of hyper-IgM syndrome has been characterized in three patients from France and Japan. The symptoms are similar to hyper IgM syndrome type 2, but the AICDA gene is intact.

Immunoglobulin class switching, also known as isotype switching, isotypic commutation or class-switch recombination (CSR), is a biological mechanism that changes a B cell's production of immunoglobulin from one type to another, such as from the isotype IgM to the isotype IgG. During this process, the constant-region portion of the antibody heavy chain is changed, but the variable region of the heavy chain stays the same. Since the variable region does not change, class switching does not affect antigen specificity. Instead, the antibody retains affinity for the same antigens, but can interact with different effector molecules.

In immunology, an idiotype is a shared characteristic between a group of immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor (TCR) molecules based upon the antigen binding specificity and therefore structure of their variable region. The variable region of antigen receptors of T cells (TCRs) and B cells (immunoglobulins) contain complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) with unique amino acid sequences. They define the surface and properties of the variable region, determining the antigen specificity and therefore the idiotope of the molecule. Immunoglobulins or TCRs with a shared idiotope are the same idiotype. Antibody idiotype is determined by:

CD48 antigen also known as B-lymphocyte activation marker (BLAST-1) or signaling lymphocytic activation molecule 2 (SLAMF2) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the CD48 gene.

Immunoglobulin lambda locus, also known as IGL@, is a region on the q arm of human chromosome 22, region 11.22 (22q11.22) that contains genes for the lambda light chains of antibodies.

Junctional diversity describes the DNA sequence variations introduced by the improper joining of gene segments during the process of V(D)J recombination. This process of V(D)J recombination has vital roles for the vertebrate immune system, as it is able to generate a huge repertoire of different T-cell receptor (TCR) and immunoglobulin molecules required for pathogen antigen recognition by T-cells and B cells, respectively.

In molecular biology, a framework region is a subdivision of the variable region (Fab) of the antibody. The variable region is composed of seven amino acid regions, four of which are framework regions and three of which are hypervariable regions. The framework region makes up about 85% of the variable region. Located on the tips of the Y-shaped molecule, the framework regions are responsible for acting as a scaffold for the complementarity determining regions (CDR), also referred to as hypervariable regions, of the Fab. These CDRs are in direct contact with the antigen and are involved in binding antigen, while the framework regions support the binding of the CDR to the antigen and aid in maintaining the overall structure of the four variable domains on the antibody. To increase its stability, the framework region has less variability in its amino acid sequences compared to the CDR.

Genome instability refers to a high frequency of mutations within the genome of a cellular lineage. These mutations can include changes in nucleic acid sequences, chromosomal rearrangements or aneuploidy. Genome instability does occur in bacteria. In multicellular organisms genome instability is central to carcinogenesis, and in humans it is also a factor in some neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or the neuromuscular disease myotonic dystrophy.

In molecular biology, kataegis describes a pattern of localized hypermutations identified in some cancer genomes, in which a large number of highly patterned basepair mutations occur in a small region of DNA. The mutational clusters are usually several hundred basepairs long, alternating between a long range of C→T substitutional pattern and a long range of G→A substitutional pattern. This suggests that kataegis is carried out on only one of the two template strands of DNA during replication. Compared to other cancer-related mutations, such as chromothripsis, kataegis is more commonly seen; it is not an accumulative process but likely happens during one cycle of replication.

Nina Papavasiliou is an immunologist and Helmholtz Professor in the Division of Immune Diversity at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, Germany. She is also an adjunct professor at the Rockefeller University, where she was previously associate professor and head of the Laboratory of Lymphocyte Biology. She is best known for her work in the fields of DNA and RNA editing.

A somatic mutation is a change in the DNA sequence of a somatic cell of a multicellular organism with dedicated reproductive cells; that is, any mutation that occurs in a cell other than a gamete, germ cell, or gametocyte. Unlike germline mutations, which can be passed on to the descendants of an organism, somatic mutations are not usually transmitted to descendants. This distinction is blurred in plants, which lack a dedicated germline, and in those animals that can reproduce asexually through mechanisms such as budding, as in members of the cnidarian genus Hydra.