Sleep apnea, also spelled sleep apnoea, is a sleep disorder in which pauses in breathing or periods of shallow breathing during sleep occur more often than normal. Each pause can last for a few seconds to a few minutes and they happen many times a night. In the most common form, this follows loud snoring. A choking or snorting sound may occur as breathing resumes. Because the disorder disrupts normal sleep, those affected may experience sleepiness or feel tired during the day. In children, it may cause hyperactivity or problems in school.

Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) is a condition in which severely overweight people fail to breathe rapidly or deeply enough, resulting in low oxygen levels and high blood carbon dioxide (CO2) levels. The syndrome is often associated with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which causes periods of absent or reduced breathing in sleep, resulting in many partial awakenings during the night and sleepiness during the day. The disease puts strain on the heart, which may lead to heart failure and leg swelling.

Somnolence is a state of strong desire for sleep, or sleeping for unusually long periods. It has distinct meanings and causes. It can refer to the usual state preceding falling asleep, the condition of being in a drowsy state due to circadian rhythm disorders, or a symptom of other health problems. It can be accompanied by lethargy, weakness and lack of mental agility.

Hypersomnia is a neurological disorder of excessive time spent sleeping or excessive sleepiness. It can have many possible causes and can cause distress and problems with functioning. In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), hypersomnolence, of which there are several subtypes, appears under sleep-wake disorders.

Upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS) is a sleep disorder characterized by the narrowing of the airway that can cause disruptions to sleep. The symptoms include unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, sleepiness, chronic insomnia, and difficulty concentrating. UARS can be diagnosed by polysomnograms capable of detecting Respiratory Effort-related Arousals. It can be treated with lifestyle changes, orthodontics, surgery, or CPAP therapy. UARS is considered a variant of sleep apnea, although some scientists and doctors believe it to be a distinct disorder.

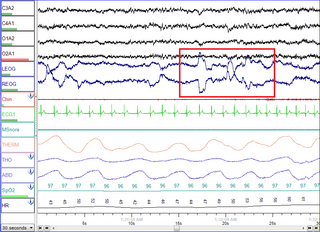

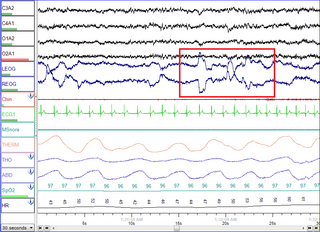

Polysomnography (PSG), a type of sleep study, is a multi-parameter study of sleep and a diagnostic tool in sleep medicine. The test result is called a polysomnogram, also abbreviated PSG. The name is derived from Greek and Latin roots: the Greek πολύς, the Latin somnus ("sleep"), and the Greek γράφειν.

A mandibi splint or mandibi advancement splint is a prescription custom-made medical device worn in the mouth used to treat sleep-related breathing disorders including: obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), snoring, and TMJ disorders. These devices are also known as mandibular advancement devices, sleep apnea oral appliances, oral airway dilators, and sleep apnea mouth guards.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common sleep-related breathing disorder and is characterized by recurrent episodes of complete or partial obstruction of the upper airway leading to reduced or absent breathing during sleep. These episodes are termed "apneas" with complete or near-complete cessation of breathing, or "hypopneas" when the reduction in breathing is partial. In either case, a fall in blood oxygen saturation, a disruption in sleep, or both, may result. A high frequency of apneas or hypopneas during sleep may interfere with the quality of sleep, which – in combination with disturbances in blood oxygenation – is thought to contribute to negative consequences to health and quality of life. The terms obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) or obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) may be used to refer to OSA when it is associated with symptoms during the daytime.

The Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) is a sleep disorder diagnostic tool. It is used to measure the time elapsed from the start of a daytime nap period to the first signs of sleep, called sleep latency. The test is based on the idea that the sleepier people are, the faster they will fall asleep.

Actigraphy is a non-invasive method of monitoring human rest/activity cycles. A small actigraph unit, also called an actimetry sensor, is worn for a week or more to measure gross motor activity. The unit is usually in a wristwatch-like package worn on the wrist. The movements the actigraph unit undergoes are continually recorded and some units also measure light exposure. The data can be later read to a computer and analysed offline; in some brands of sensors the data are transmitted and analysed in real time.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is a scale intended to measure daytime sleepiness that is measured by use of a very short questionnaire. This can be helpful in diagnosing sleep disorders. It was introduced in 1991 by Dr Murray Johns of Epworth Hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

Circadian rhythm sleep disorders (CRSD), also known as circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders (CRSWD), are a family of sleep disorders which affect the timing of sleep. CRSDs arise from a persistent pattern of sleep/wake disturbances that can be caused either by dysfunction in one's biological clock system, or by misalignment between one's endogenous oscillator and externally imposed cues. As a result of this mismatch, those affected by circadian rhythm sleep disorders have a tendency to fall asleep at unconventional time points in the day. These occurrences often lead to recurring instances of disturbed rest, where individuals affected by the disorder are unable to go to sleep and awaken at "normal" times for work, school, and other social obligations. Delayed sleep phase disorder, advanced sleep phase disorder, non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder and irregular sleep–wake rhythm disorder represents the four main types of CRSD.

Hypopnea is overly shallow breathing or an abnormally low respiratory rate. Hypopnea is defined by some to be less severe than apnea, while other researchers have discovered hypopnea to have a "similar if not indistinguishable impact" on the negative outcomes of sleep breathing disorders. In sleep clinics, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome or obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome is normally diagnosed based on the frequent presence of apneas and/or hypopneas rather than differentiating between the two phenomena. Hypopnea is typically defined by a decreased amount of air movement into the lungs and can cause oxygen levels in the blood to drop. It commonly is due to partial obstruction of the upper airway.

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is characterized by persistent sleepiness and often a general lack of energy, even during the day after apparently adequate or even prolonged nighttime sleep. EDS can be considered as a broad condition encompassing several sleep disorders where increased sleep is a symptom, or as a symptom of another underlying disorder like narcolepsy, circadian rhythm sleep disorder, sleep apnea or idiopathic hypersomnia.

Sleep medicine is a medical specialty or subspecialty devoted to the diagnosis and therapy of sleep disturbances and disorders. From the middle of the 20th century, research has provided increasing knowledge of, and answered many questions about, sleep–wake functioning. The rapidly evolving field has become a recognized medical subspecialty in some countries. Dental sleep medicine also qualifies for board certification in some countries. Properly organized, minimum 12-month, postgraduate training programs are still being defined in the United States. In some countries, the sleep researchers and the physicians who treat patients may be the same people.

A sleep study is a test that records the activity of the body during sleep. There are five main types of sleep studies that use different methods to test for different sleep characteristics and disorders. These include simple sleep studies, polysomnography, multiple sleep latency tests (MSLTs), maintenance of wakefulness tests (MWTs), and home sleep tests (HSTs). In medicine, sleep studies have been useful in identifying and ruling out various sleep disorders. Sleep studies have also been valuable to psychology, in which they have provided insight into brain activity and the other physiological factors of both sleep disorders and normal sleep. This has allowed further research to be done on the relationship between sleep and behavioral and psychological factors.

Idiopathic hypersomnia(IH) is a neurological disorder which is characterized primarily by excessive sleep and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS). The condition typically becomes evident in early adulthood and most patients diagnosed with IH will have had the disorder for many years prior to their diagnosis. As of August 2021, an FDA-approved medication exists for IH called Xywav, which is oral solution of calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium oxybates; in addition to several off-label treatments (primarily FDA-approved narcolepsy medications).

Central sleep apnea (CSA) or central sleep apnea syndrome (CSAS) is a sleep-related disorder in which the effort to breathe is diminished or absent, typically for 10 to 30 seconds either intermittently or in cycles, and is usually associated with a reduction in blood oxygen saturation. CSA is usually due to an instability in the body's feedback mechanisms that control respiration. Central sleep apnea can also be an indicator of Arnold–Chiari malformation.

Sleep disorder is a common repercussion of traumatic brain injury (TBI). It occurs in 30%-70% of patients with TBI. TBI can be distinguished into two categories, primary and secondary damage. Primary damage includes injuries of white matter, focal contusion, cerebral edema and hematomas, mostly occurring at the moment of the trauma. Secondary damage involves the damage of neurotransmitter release, inflammatory responses, mitochondrial dysfunctions and gene activation, occurring minutes to days following the trauma. Patients with sleeping disorders following TBI specifically develop insomnia, sleep apnea, narcolepsy, periodic limb movement disorder and hypersomnia. Furthermore, circadian sleep-wake disorders can occur after TBI.

Behavioral sleep medicine (BSM) is a field within sleep medicine that encompasses scientific inquiry and clinical treatment of sleep-related disorders, with a focus on the psychological, physiological, behavioral, cognitive, social, and cultural factors that affect sleep, as well as the impact of sleep on those factors. The clinical practice of BSM is an evidence-based behavioral health discipline that uses primarily non-pharmacological treatments. BSM interventions are typically problem-focused and oriented towards specific sleep complaints, but can be integrated with other medical or mental health treatments. The primary techniques used in BSM interventions involve education and systematic changes to the behaviors, thoughts, and environmental factors that initiate and maintain sleep-related difficulties.