Karl Marx was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist and socialist revolutionary.

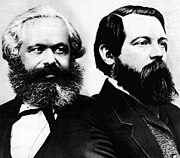

The Communist Manifesto, originally the Manifesto of the Communist Party, is an 1848 political document by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London just as the Revolutions of 1848 began to erupt, the Manifesto was later recognised as one of the world's most influential political documents. It presents an analytical approach to the class struggle and the conflicts of capitalism and the capitalist mode of production, rather than a prediction of communism's potential future forms.

In economics and sociology, the means of production are physical and non-financial inputs used in the production of economic value. These include raw materials, facilities, machinery and tools used in the production of goods and services. In the terminology of classical economics, the means of production are the "factors of production" minus financial and human capital.

Bourgeoisie is a polysemous French term that can mean:

Universal class is a category derived from the philosophy of Hegel, redefined and popularized by Karl Marx. In Marxism it denotes that class of people within a stratified society for which, at a given point in history, self-interested action coincides with the needs of humanity as a whole.

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that views class relations and social conflict using a materialist interpretation of historical development and takes a dialectical view of social transformation. It originates from the works of 19th-century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism has developed into many different branches and schools of thought, with the result that there is now no single definitive Marxist theory.

While Marxists propose replacing the bourgeois state with a proletarian semi-state through revolution, which would eventually wither away, anarchists warn that the state must be abolished along with capitalism. Nonetheless, the desired end results, a stateless, communal society, are the same.

Marxian class theory asserts that an individual’s position within a class hierarchy is determined by their role in the production process, and argues that political and ideological consciousness is determined by class position. A class is those who share common economic interests, are conscious of those interests, and engage in collective action which advances those interests. Within Marxian class theory, the structure of the production process forms the basis of class construction.

Karl Marx's ideas about the state can be divided into three subject areas: pre-capitalist states, states in the capitalist era and the state in post-capitalist society. Overlaying this is the fact that his own ideas about the state changed as he grew older, differing in his early pre-communist phase, the young Marx phase which predates the unsuccessful 1848 uprisings in Europe and in his mature, more nuanced work.

The 1848 Revolution in France, sometimes known as the February Revolution, was one of a wave of revolutions in 1848 in Europe. In France the revolutionary events ended the July Monarchy (1830–1848) and led to the creation of the French Second Republic.

Lumpenproletariat is a term used primarily by Marxist theorists to describe the underclass devoid of class consciousness. Coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the 1840s, they used it to refer to the unthinking lower strata of society exploited by reactionary and counter-revolutionary forces, particularly in the context of the revolutions of 1848. They dismissed its revolutionary potential and contrasted it with the proletariat. Among other groups criminals, vagabonds, and sex workers are usually included in this category.

Classical Marxism refers to the economic, philosophical and sociological theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as contrasted with later developments in Marxism, especially Leninism and Marxism–Leninism.

Revolutionary socialism is the socialist doctrine that social revolution is necessary in order to bring about structural changes to society. More specifically, it is the view that revolution is a necessary precondition for a transition from capitalism to socialism. Revolution is not necessarily defined as a violent insurrection; it is defined as seizure of political power by mass movements of the working class so that the state is directly controlled or abolished by the working class as opposed to the capitalist class and its interests. Revolutionary socialists believe such a state of affairs is a precondition for establishing socialism and orthodox Marxists believe that it is inevitable but not predetermined.

Mahir Çayan was a Turkish communist revolutionary and the leader of People's Liberation Party-Front of Turkey. He was a Marxist–Leninist revolutionary leader. On 30 March 1972, he was killed by soldiers with nine friends in Kızıldere village.

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is the state of affairs in which the working class hold political power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, realised by the nationalisation of the means of production, from private ownership to collective ownership. The revolutionary socialist Joseph Weydemeyer coined the term "dictatorship of the proletariat", which Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels adopted to their philosophy of political economy. The historical exemplar of the dictatorship of the proletariat is the Paris Commune (1871), a socialist-democratic opposition to peace with Germany and the socio-economic conservatism of the French Third Republic, which controlled the French capital city for two months, before being suppressed by Prussian soldiers.

The proletariat is the class of wage-earners in an economic society whose only possession of significant material value is their labour-power. A member of such a class is a proletarian.

Principles of Communism is a brief 1847 work written by Friedrich Engels, the co-founder of Marxism. It is structured as a catechism, containing 25 questions about communism for which answers are provided. In the text, Engels presents core ideas of Marxism such as historical materialism, class struggle, and proletarian revolution. Principles of Communism served as the draft version for the Communist Manifesto.

Permanent revolution is the strategy of a revolutionary class pursuing its own interests independently and without compromise or alliance with opposing sections of society. As a term within Marxist theory, it was first coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels by at least 1850, but since then it has been used to refer to different concepts by different theorists, most notably Leon Trotsky.

Historical materialism, also known as the materialist conception of history, is a methodology used by some communist and Marxist historiographers that focuses on human societies and their development through history, arguing that history is the result of material conditions rather than ideals. This was first articulated by Karl Marx (1818–1883) as the "materialist conception of history". It is principally a theory of history which asserts that the material conditions of a society's mode of production or in Marxist terms, the union of a society's productive forces and relations of production, fundamentally determine society's organization and development. Historical materialism is an example of Marx and Engel's scientific socialism, attempting to show that socialism and communism are scientific necessities rather than philosophical ideals.

Fascist syndicalism was a trade syndicate movement that rose out of the pre-World War II provenance of the revolutionary syndicalism movement led mostly by Edmondo Rossoni, Sergio Panunzio, A. O. Olivetti, Michele Bianchi, Alceste De Ambris, Paolo Orano, Massimo Rocca, and Guido Pighetti, under the influence of Georges Sorel, who was considered the “‘metaphysician’ of syndicalism.” The Fascist Syndicalists differed from other forms of fascism in that they generally favored class struggle, worker-controlled factories and hostility to industrialists, which lead historians to portray them as “leftist fascist idealists” who “differed radically from right fascists.” Generally considered one of the more radical Fascist syndicalists in Italy, Rossoni was the “leading exponent of fascist syndicalism.”, and sought to infuse nationalism with “class struggle.”