| Therizinosaur | |

|---|---|

| |

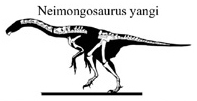

| Reconstructed skeleton of Nothronychus graffami | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Aveairfoila |

| Clade: | †Therizinosauria Russell, 1997 |

| Synonyms | |

Segnosauria Barsbold, 1980 Contents | |

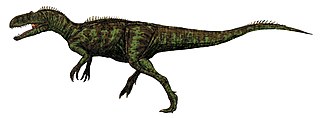

Therizinosaurs (or segnosaurs) were theropod dinosaurs belonging to the clade Therizinosauria. Therizinosaur fossils have been found in Early through Late Cretaceous deposits in Mongolia, the People's Republic of China, western North America and possibly Australia [1] . Various features of the forelimbs, skull and pelvis unite these finds as both theropods and as maniraptorans, close relatives to birds.

Theropoda or theropods are a dinosaur suborder that is characterized by hollow bones and three-toed limbs. They are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs, although a 2017 paper has instead placed them in the proposed clade Ornithoscelida as the closest relatives of the Ornithischia. Theropods were ancestrally carnivorous, although a number of theropod groups evolved to become herbivores, omnivores, piscivores, and insectivores. Theropods first appeared during the Carnian age of the late Triassic period 231.4 million years ago (Ma) and included the sole large terrestrial carnivores from the Early Jurassic until at least the close of the Cretaceous, about 66 Ma. In the Jurassic, birds evolved from small specialized coelurosaurian theropods, and are today represented by about 10,500 living species.

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago, although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is the subject of active research. They became the dominant terrestrial vertebrates after the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event 201 million years ago; their dominance continued through the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Reverse genetic engineering and the fossil record both demonstrate that birds are modern feathered dinosaurs, having evolved from earlier theropods during the late Jurassic Period. As such, birds were the only dinosaur lineage to survive the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago. Dinosaurs can therefore be divided into avian dinosaurs, or birds; and non-avian dinosaurs, which are all dinosaurs other than birds. This article deals primarily with non-avian dinosaurs.

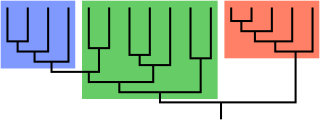

A clade, also known as monophyletic group, is a group of organisms that consists of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants, and represents a single "branch" on the "tree of life".

The name therizinosaur is derived from the Greek θερίζω [2] therízein, meaning 'to reap' or 'to cut off', and σαῦρος [3] saûros meaning 'lizard'. The older name segnosaur is derived from Latin segnis meaning 'slow' or 'sluggish', and Greek σαυρος, sauros, meaning 'lizard'.

The Ancient Greek language includes the forms of Greek used in Ancient Greece and the ancient world from around the 9th century BCE to the 6th century CE. It is often roughly divided into the Archaic period, Classical period, and Hellenistic period. It is antedated in the second millennium BCE by Mycenaean Greek and succeeded by medieval Greek.

Latin is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. The Latin alphabet is derived from the Etruscan and Greek alphabets, and ultimately from the Phoenician alphabet.