Related Research Articles

A shanty town, squatter area or squatter settlement is a settlement of improvised buildings known as shanties or shacks, typically made of materials such as mud and wood. A typical shanty town is squatted and in the beginning lacks adequate infrastructure, including proper sanitation, safe water supply, electricity and street drainage. Over time, shanty towns can develop their infrastructure and even change into middle class neighbourhoods. They can be small informal settlements or they can house millions of people.

Jockin Arputham was an Indian community leader and activist, known for his campaigning work of more than 40 years on issues related to slums and shanty towns. He was born in Karnataka, India and moved to Mumbai, where he quickly became politicized and established himself as a community leader. In 2014, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, alongside the organisation he helped to found, Slum Dwellers International. In 2011, he received the Padma Shri in New Delhi for his contributions to social work, presented by the President of India.

Slum/Shack Dwellers International (SDI), is a global social movement of the urban poor that started in 1996. It forms a network of community-based organisations in more than 30 countries across Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean.

The National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF) in India was established by Jockin Arputham when he fought on behalf of a community of 70,000 to appeal a 1976 eviction order. It is a national organization which brings together multiple communities and their leaders who live in slum settlements around India. NSDF along with Mahila Milan are one of the oldest members of the Urban Poor Fund International Network. Due to the efforts of NSDF, around 90 buildings and 300 toilet blocks have been constructed in Mumbai, providing houses and sanitation to over 35,000 families. Additionally, around 100 toilet blocks have been constructed in Pune.

Mahila Milan is a self-organised, decentralised collective of female pavement dwellers in Bombay. The group works with issues such as housing, sanitation, and grassroots lending schemes. It aims at gaining women equal recognition for improvement of their communities, while indulging in important decision making activities. The loans granted by the group to its members in times of need, are sanctioned in the name of the woman of the house.

Pavement dwellers refers to informal housing built on the footpaths/pavements of city streets. The structures use the walls or fences which separate properties from the pavement and street outside. Materials include cloth, corrugated iron, cardboard, wood, plastic, and sometimes also bricks or cement.

Sheela Patel is an activist and academic involved with people living in slums and shanty towns.

The Slum Rehabilitation Act 1995 was passed by the government of the Indian state Maharashtra to protect the rights of swamp dwellers and promote the development of swamp areas. The Act protected from eviction, anyone who could produce a document proving they lived in the city of Mumbai before January 1995, regardless if they lived on the swamp or other kinds of marsh land. The ACT was the result of policy development that included grassroots slum dweller organisations, particularly SPARC.

Housing in India varies from palaces of erstwhile maharajas to modern apartment buildings in big cities to tiny huts in far-flung villages. The Human Rights Measurement Initiative finds that India is doing 60.9% of what should be possible at its level of income for the right to housing.

The KwaZulu-Natal Elimination and Prevention of Re-emergence of Slums Act, 2007 was a provincial law dealing with land tenure and evictions in the province of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa.

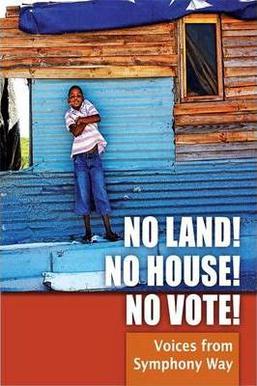

No Land! No House! No Vote! Voices from Symphony Way is an anthology published in 2011 of 45 factual tales written and edited by the Symphony Way Pavement Dwellers.

Homelessness is a major issue in India. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights defines 'homeless' as those who do not live in a regular residence. The United Nations Economic and Social Council Statement has a broader definition for homelessness; it defines homelessness as follows: ‘When we are talking about housing, we are not just talking about four walls and a roof. The right to adequate housing is about security of tenure, affordability, access to services and cultural adequacy. It is about protection from forced eviction and displacement, fighting homelessness, poverty and exclusion. India defines 'homeless' as those who do not live in Census houses, but rather stay on pavements, roadsides, railway platforms, staircases, temples, streets, in pipes, or other open spaces. There are 1.77 million homeless people in India, or 0.15% of the country's total population, according to the 2011 census consisting of single men, women, mothers, the elderly, and the disabled. However, it is argued that the numbers are far greater than accounted by the point in time method. For example, while the Census of 2011 counted 46,724 homeless individuals in Delhi, the Indo-Global Social Service Society counted them to be 88,410, and another organization called the Delhi Development Authority counted them to be 150,000. Furthermore, there is a high proportion of mentally ill and street children in the homeless population. There are 18 million street children in India, the largest number of any country in the world, with 11 million being urban. Finally, more than three million men and women are homeless in India's capital city of New Delhi; the same population in Canada would make up approximately 30 electoral districts. A family of four members has an average of five homeless generations in India.

Illegal housing in India consists of huts or shanties built on land not owned by the residents and illegal buildings constructed on land not owned by the builders or developers. Although illegal buildings may afford some basic services, such as electricity, in general, illegal housing does not provide services that afford for healthy, safe environments.

Chennai is the capital city of the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu and is the fourth largest metropolitan city in the country. A total of 30% of Chennai's population resided in slums as of 2011. The state government of Tamil Nadu has established a slum clearance Board, with a minister heading it. Out of the major cities with the highest population in slums, Chennai ranks fourth after Mumbai, Hyderabad and Kolkota. Rapid urbanization and employment in the unorganized sector is the major factor for the slum population in Chennai.

Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation was a 1985 case in the Supreme Court of India. It came before the Court as a written petition by pavement and slum dwellers in Bombay, seeking to be allowed to stay on the pavements against their order of eviction during the monsoon months by the Bombay Municipal Corporation.

Cheeta Camp is a low lying area near Trombay, Mumbai, Maharashtra. It is a part of Municipal M-East Ward and located along the Arabian Seafront.

Slum clearance in India is used as an urban renewal approach to redevelop and transform poor and low income settlements into new developments or housing. Millions of people live in slum dwellings across India and many migrate to live in the slums from rural villages, often in search of work opportunities. Houses are typically built by the slum dwellers themselves and violence has been known to occur when developers attempt to clear the land of slum dwellings.

Shadow Cities: A Billion Squatters, A New Urban World is a 2004 book by Robert Neuwirth. He wrote it after visiting informal settlements such as Dharavi, Kibera and Rocinha.

Squatting in Ghana is the occupation of unused land or derelict buildings without the permission of the owner. Informal settlements are found in cities such as Kumasi and the capital Accra. Ashaiman, now a town of 100,000 people, was swelled by squatters. In central Accra, next to Agbogbloshie, the Old Fadama settlement houses an estimated 80,000 people and is subject to a controversial discussion about eviction. The residents have been supported by Amnesty International, the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions and Shack Dwellers International.

References

- 1 2 Patel, Sheela; Arputham, Jockin; Bartlett, Sheridan (23 December 2015). ""We beat the path by walking": How the women of Mahila Milan in India learned to plan, design, finance and build housing". Environment and Urbanization. 28 (1): 223–240. doi: 10.1177/0956247815617440 .

- ↑ Count me in: Surveying for tenure security and urban land management. UN HABITAT. 2010. pp. 15–18. ISBN 9789211322286.

- 1 2 "DEMOLITIONS TO DIALOGUE: Mahila Milan - learning to talk to its city and municipality" (PDF). UCL. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ Development Gateway Foundation: Urban Development: Empowering Slum Dwellers: Interview with Sheela Patel, 7 September 2004 Archived 2006-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Patel, Sheela; Burra, Sundar. "Norms and standards in urban development: the experience of an urban alliance in India". GOV.UK. Department for International Development. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ Gupta, Vishesh (7 December 2019). "Invisible urban poor: The pavement dwellers of India". Counterview. Retrieved 10 May 2020.