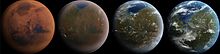

The Mars Society is a nonprofit organization that advocates for human exploration and colonization of Mars. It was founded by Robert Zubrin in 1998 and its principles are based on Zubrin's Mars Direct philosophy, which aims to make human missions to Mars as feasible as possible. The Mars Society generates interest in the Mars program by garnering support from the public and through lobbying. Many current and former Mars Society members are influential in the wider spaceflight community, such as Buzz Aldrin and Elon Musk.

Space Exploration Technologies Corporation, commonly referred to as SpaceX, is an American spacecraft manufacturer, launch service provider and satellite communications company headquartered in Hawthorne, California. The company was founded in 2002 by Elon Musk with the goal of reducing space transportation costs and ultimately developing a sustainable colony on Mars. The company currently produces and operates the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets along with the Dragon and Starship spacecraft.

Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A) is the first of Launch Complex 39's three launch pads, located at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Merritt Island, Florida. The pad, along with Launch Complex 39B, was first designed to accommodate the Saturn V launch vehicle. Typically used to launch NASA's crewed spaceflight missions since the late 1960s, the pad was leased by SpaceX and has been modified to support their launch vehicles.

Dragon is a family of spacecraft developed and produced by American private space transportation company SpaceX. The first family member, later named Dragon 1, flew 23 cargo missions to the ISS between 2010 and 2020 before retiring. This version, not designed to carry astronauts, was funded by NASA with $396 million awarded through the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program, with SpaceX announced as a winner of the first round of funding on August 18, 2006.

Vertical takeoff, vertical landing (VTVL) is a form of takeoff and landing for rockets. Multiple VTVL craft have flown. The most successful VTVL vehicle was the Apollo Lunar Module which delivered the first humans to the Moon. Building on the decades of development, SpaceX utilised the VTVL concept for its flagship Falcon 9 first stage, which has delivered over two hundred successful powered landings so far.

Falcon Heavy is a partially reusable super heavy-lift launch vehicle that can carry cargo into Earth orbit, and beyond. It is designed, manufactured and launched by American aerospace company SpaceX.

SpaceX has privately funded the development of orbital launch systems that can be reused many times, similar to the reusability of aircraft. SpaceX has developed technologies over the last decade to facilitate full and rapid reuse of space launch vehicles. The project's long-term objectives include returning a launch vehicle first stage to the launch site within minutes and to return a second stage to the launch pad, following orbital realignment with the launch site and atmospheric reentry in up to 24 hours. SpaceX's long term goal would have been reusability of both stages of their orbital launch vehicle, and the first stage would be designed to allow reuse a few hours after return. Development of reusable second stages for Falcon 9 was later abandoned in favor of developing Starship, however, SpaceX developed reusable payload fairings for the Falcon 9.

The SpaceX Red Dragon was a 2011–2017 concept for using an uncrewed modified SpaceX Dragon 2 for low-cost Mars lander missions to be launched using Falcon Heavy rockets.

Since the founding of SpaceX in 2002, the company has developed four families of rocket engines — Merlin, Kestrel, Draco and SuperDraco — and is currently developing another rocket engine: Raptor, and after 2020, a new line of methalox thrusters.

A super heavy-lift launch vehicle is a rocket that can lift to low Earth orbit a "super heavy payload", which is defined as more than 50 metric tons (110,000 lb) by the United States and as more than 100 metric tons (220,000 lb) by Russia. It is the most capable launch vehicle classification by mass to orbit, exceeding that of the heavy-lift launch vehicle classification.

The Mars race, race to Mars or race for Mars is the competitive environment between various national space agencies, "New Space" and aerospace manufacturers involving crewed missions to Mars, land on Mars, or set a crewed base there. Some of these efforts are part of a greater Mars colonization vision, while others are for glory, or scientific endeavours. Some of this competitiveness is part of the New Space race.

This is a corporate history of SpaceX, an American aerospace manufacturer and spacetransport services company founded by Elon Musk.

The dearMoonproject is a lunar tourism mission and art project conceived and financed by Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa. It will make use of a SpaceX Starship spacecraft on a private spaceflight flying a single circumlunar trajectory around the Moon. The passengers will be Maezawa and eight other civilians, and there may be one or two crew members. The project was unveiled in September 2018 and was scheduled to launch in 2023. It has since been indefinitely delayed until Starship completes development. The project objective is to have eight passengers travel with Maezawa for free around the Moon on a six-day tour. Maezawa said that they expect the experience of space tourism to inspire the accompanying passengers in the creation of something new. If successful, the art would be exhibited some time after returning to Earth with the goal of promoting peace around the world.

Starship is a two-stage super heavy-lift launch vehicle under development by SpaceX. As of April 2024, it is the largest and most powerful rocket ever flown. Starship's primary objective is to lower launch costs significantly via economies of scale. This is achieved by reusing both rocket stages, increasing payload mass to orbit, increasing launch frequency, creating a mass-manufacturing pipeline, and adapting it to a wide range of space missions. Starship is the latest project in SpaceX's decades-long reusable launch system development program and ambition of colonizing Mars.

The Artemis program is a Moon exploration program that is led by the United States' National Aeronoautics and Space Administration (NASA) and was formally established in 2017 via Space Policy Directive 1. The Artemis program is intended to reestablish a human presence on the Moon for the first time since the Apollo 17 moon mission in 1972. The program's stated long-term goal is to establish a permanent base on the Moon to facilitate human missions to Mars.

SpaceX Starship flight tests include fourteen launches of prototype rockets during 2019–2024 for the SpaceX Starship launch vehicle development program. Eleven test flights were of single-stage Starship spacecraft flying low-altitude tests (2019–2021), while three were orbital trajectory flights of the entire Starship launch vehicle (2023–2024), consisting of a Starship spacecraft second-stage prototype atop a Super Heavy first-stage booster prototype. None of the flights to date has carried an operational payload. More flight tests are planned in 2024 and 2025.

Raptor is a family of rocket engines developed and manufactured by SpaceX. The engine is a full-flow staged combustion cycle (FFSC) engine powered by cryogenic liquid methane and liquid oxygen ("methalox").

Starship HLS is a lunar lander variant of the Starship spacecraft that is slated to transfer astronauts from a lunar orbit to the surface of the Moon and back. It is being designed and built by SpaceX under the Human Landing System contract to NASA as a critical element of NASA's Artemis program to land a crew on the Moon.

Before settling on the 2018 Starship design, SpaceX successively presented a number of reusable super-heavy lift vehicle proposals. These preliminary spacecraft designs were known under various names.