The 1110s was a decade of the Julian Calendar which began on January 1, 1110, and ended on December 31, 1119.

Year 1113 (MCXIII) was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar.

Year 1114 (MCXIV) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar.

Ramon Berenguer IIIthe Great was the count of Barcelona, Girona, and Ausona from 1086, Besalú from 1111, Cerdanya from 1117, and count of Provence in the Holy Roman Empire, from 1112, all until his death in Barcelona in 1131. As Ramon Berenguer I, he was Count of Provence in right of his wife.

The Senyera is a vexillological symbol based on the coat of arms of the Crown of Aragon, which consists of four red stripes on a yellow field. This coat of arms, often called bars of Aragon, or simply "the four bars", historically represented the King of the Crown of Aragon.

The Principality of Catalonia was a medieval and early modern state in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula. During most of its history it was in dynastic union with the Kingdom of Aragon, constituting together the Crown of Aragon. Between the 13th and the 18th centuries, it was bordered by the Kingdom of Aragon to the west, the Kingdom of Valencia to the south, the Kingdom of France and the feudal lordship of Andorra to the north and by the Mediterranean Sea to the east. The term Principality of Catalonia was official until the 1830s, when the Spanish government implemented the centralized provincial division, but remained in popular and informal contexts. Today, the term Principat (Principality) is used primarily to refer to the autonomous community of Catalonia in Spain, as distinct from the other Catalan Countries, and usually including the historical region of Roussillon in Southern France.

The County of Barcelona was a polity in northeastern Iberian Peninsula, originally located in the southern frontier region of the Carolingian Empire. In the 10th century, the Counts of Barcelona progressively achieved independence from Frankish rule, becoming hereditary rulers in constant warfare with the Islamic Caliphate of Córdoba and its successor states. The counts, through marriage, alliances and treaties, acquired or vassalized the other Catalan counties and extended their influence over Occitania. In 1164, the County of Barcelona entered a personal union with the Kingdom of Aragon. Thenceforward, the history of the county is subsumed within that of the Crown of Aragon, but the city of Barcelona remained preeminent within it.

Douce I was the daughter of Gilbert I of Gévaudan and Gerberga of Provence and wife of Ramon Berenguer III, Count of Barcelona. In 1112, she inherited the county of Provence through her mother. She married Ramon Berenguer at Arles on 3 February that year.

Olegarius Bonestruga was the Bishop of Barcelona from 1116 and Archbishop of Tarragona from 1118 until his death. He was an intimate of Ramon Berenguer III, Count of Barcelona, and often accompanied the count on military ventures.

Berenguer de Montagut was a Catalan architect, master builder on Santa Maria del Mar.

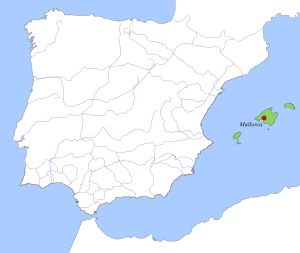

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a province and autonomous community of Spain, with Palma de Mallorca being its capital and largest city.

The Liber maiolichinusde gestis pisanorum illustribus is a Medieval Latin epic chronicle in 3,500 hexameters, written between 1117 and 1125, detailing the Pisan-led joint military expedition of Italians, Catalans, and Occitans against the taifa of the Balearic Islands, in particular Majorca and Ibiza, in 1113–5. It was commissioned by the commune of Pisa, and its anonymous author was probably a cleric. It survives in three manuscripts. The Liber is notable for containing the earliest known reference to "Catalans" (Catalanenses), treated as an ethnicity, and to "Catalonia" (Catalania), as their homeland.

Hugh II was the Count of Empúries from 1078 until his death. He was the eldest son of Ponç I and Adelaida de Besalú, and succeeded his father in Empúries while his brother, Berenguer, was given the Viscounty of Peralada.

Pietro Moriconi was the Archbishop of Pisa from 1105, succeeding Dagobert. According to tradition he belonged to the noble lineage of Moriconi of Vico. He first appears as archbishop in a document of 19 March 1106, and is credited with strengthening the Pisan church. On 13 April 1113, he preached a crusade against the Balearic Islands to free captive Christians there. He went to Rome to receive Pope Paschal II's blessing for the expedition, which he also helped lead in person. He interfered to quash peace negotiations that ran counter to Pisa's interests. He died in 1119, and was buried on 10 September in the Pisan Duomo.

The Norwegian Crusade, led by Norwegian King Sigurd I, was a crusade or a pilgrimage that lasted from 1107 to 1111, in the aftermath of the First Crusade. The Norwegian Crusade marks the first time a European king personally went to the Holy Land.

In 1015 and again in 1016, the forces of Mujāhid al-ʿĀmirī from the taifa of Denia and the Balearics, in the east of Muslim Spain (al-Andalus), attacked Sardinia and attempted to establish control over it. In both these years joint expeditions from the maritime republics of Pisa and Genoa repelled the invaders. These Pisan–Genoese expeditions to Sardinia were approved and supported by the Papacy in aid of the sovereign Sardinian medieval kingdoms, known as Judicates, which resisted autonomously after the collapse of the Byzantine rule on the island. Modern historians often see them as proto-Crusades. After their victory, the Italian cities turned on each other. For this reason, the Christian sources for the expedition are primarily from Pisa, which celebrated its double victory over the Muslims and the Genoese with an inscription on the walls of its Duomo.

The conquest of the island of Majorca on behalf of the Roman Catholic kingdoms was carried out by King James I of Aragon between 1229 and 1231. The pact to carry out the invasion, concluded between James I and the ecclesiastical and secular leaders, was ratified in Tarragona on 28 August 1229. It was open and promised conditions of parity for all who wished to participate.

The Aragonese conquest of Sardinia took place between 1323 and 1326. The island of Sardinia was at the time subject to the influence of the Republic of Pisa, the Pisan della Gherardesca family, Genoa and of the Genoese families of Doria and the Malaspina; the only native political entity survived was the Judicate of Arborea, allied with the Crown of Aragon. The financial difficulties due to the wars in Sicily, the conflict with the Crown of Castile in the land of Murcia and Alicante (1296–1304) and the failed attempt to conquer Almeria (1309) explain the delay of James II of Aragon in bringing the conquest of Sardinia, enfeoffed to him by Pope Boniface VIII in 1297.

Boso was a Roman Catholic cardinal, priest of Sant'Anastasia al Palatino (1116–1122) and bishop of Turin (1122–1126×28). He was a frequent apostolic legate, making four separate trips to Spain in this capacity. In Spain he proclaimed a crusade to re-conquer the Balearics and held several synods to establish the Gregorian reforms. In Turin, he introduced the truce of God to curb private warfare.

The Battle of Ibiza, also known as The Raid on Ibiza, was a part of a military campaign against the Muslims of the Balearic Islands. Islamic scholars have referred to the Norwegian raids in the region as part of a larger history of Islamic Spain. After winning a battle at the island of Formentera, Sigurd would go on to attack the islands of Ibiza, which is only separated from Formentera by a narrow channel.