The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard was the first United States Navy shipyard and was historically important for nearly two centuries.

The United Mine Workers of America is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the United States and Canada. Although its main focus has always been on workers and their rights, the UMW of today also advocates for better roads, schools, and universal health care. By 2014, coal mining had largely shifted to open pit mines in Wyoming, and there were only 60,000 active coal miners. The UMW was left with 35,000 members, of whom 20,000 were coal miners, chiefly in underground mines in Kentucky and West Virginia. However it was responsible for pensions and medical benefits for 40,000 retired miners, and for 50,000 spouses and dependents.

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is a ceremonial and administrative center for the United States Navy, located in the federal national capital city of Washington, D.C.. It is the oldest shore establishment / base of the United States Navy, established 1799, situated along the north shore of the Anacostia River in the adjacent Navy Yard neighborhood of Southeast, Washington, D.C.

Isaac Hull was a Commodore in the United States Navy. He commanded several famous U.S. naval warships including USS Constitution and saw service in the undeclared naval Quasi War with the revolutionary French Republic (France) 1796–1800; the Barbary Wars, with the Barbary states in North Africa; and the War of 1812 (1812–1815), for the second time with Great Britain. In the latter part of his career he was Commandant of the Washington Navy Yard in the national capital of Washington, D.C., and later the Commodore of the Mediterranean Squadron. For the infant U.S. Navy, the battle of USS Constitution vs HMS Guerriere on August 19, 1812, at the beginning of the war, was the most important single ship action of the War of 1812 and one that made Isaac Hull a national hero.

The Coal strike of 1902 was a strike by the United Mine Workers of America in the anthracite coalfields of eastern Pennsylvania. Miners struck for higher wages, shorter workdays, and the recognition of their union. The strike threatened to shut down the winter fuel supply to major American cities. At that time, residences were typically heated with anthracite or "hard" coal, which produces higher heat value and less smoke than "soft" or bituminous coal.

The eight-hour day movement was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses of working time.

The following is a timeline of labor history, organizing & conflicts, from the early 1600s to present.

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 was the first strike that spread across multiple states in the U.S. The strike finally ended 52 days later, after it was put down by unofficial militias, the National Guard, and federal troops. Because of economic problems and pressure on wages by the railroads, workers in numerous other states, from New York, Pennsylvania and Maryland, into Illinois and Missouri, also went out on strike. An estimated 100 people were killed in the unrest across the country. In Martinsburg, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and other cities, workers burned down and destroyed both physical facilities and the rolling stock of the railroads—engines and railroad cars. Some locals feared that workers were rising in revolution, similar to the Paris Commune of 1871, while others joined their efforts against the railroads.

The Lowell mill girls were young female workers who came to work in textile mills in Lowell, Massachusetts during the Industrial Revolution in the United States. The workers initially recruited by the corporations were daughters of New England farmers, typically between the ages of 15 and 35. By 1840, at the height of the Textile Revolution, the Lowell textile mills had recruited over 8,000 workers, with women making up nearly three-quarters of the mill workforce.

Josiah Fox (1763–1847) was a British naval architect noted for his involvement in the design and construction of the first significant warships of the United States Navy.

The General Strike of 1910 was a labor strike by trolley workers of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company that grew to a citywide riot and general strike in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The 1835 Paterson textile strike took place in Paterson, New Jersey, involved more than 2,000 workers from 20 textile mills across the city. The strikers, many of whom were children and of Irish descent, were seeking a reduction in daily working hours from thirteen and a half hours to eleven hours. Support from other workers in Paterson and nearby cities allowed the strikers to sustain their efforts for two weeks. Employers refused to negotiate with the workers, and were able to break the strike by unilaterally declaring a reduction in work hours to twelve hours daily during the week and nine hours on Saturdays. Many leaders of the strike and their family were blacklisted by employers in Paterson after it ended. Due to the lack of long distance communication and the lack of birth certificates, many people who were blacklisted ran off using a new identity, the most famous person to do this is the infamous Anthony Gunk.

The Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations was an American trade union founded in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1827.

The Morewood massacre was an armed labor-union conflict in Morewood, Pennsylvania, in Westmoreland County, west of the present-day borough Mount Pleasant in 1891.

The Los Angeles streetcar strike of 1919 was the most violent revolt against the open-shop policies of the Pacific Electric Railway Company in Los Angeles. Labor organizers had fought for over a decade to increase wages, decrease work hours, and legalize unions for streetcar workers of the Los Angeles basin. After having been denied unionization rights and changes in work policies by the National War Labor Board, streetcar workers broke out in massive protest before being subdued by local armed police force.

The Snow Riot was a riot and lynch mob in Washington, D.C., that began on August 11, 1835, when a mob of angry white mechanics attacked and destroyed Beverly Snow's Epicurean Eating House, a restaurant owned by a black man. This violence, born of white men's frustration about having to compete with free blacks for jobs, touched off several days of white mob violence against free blacks, their houses, and establishments. It stopped only at President Andrew Jackson's intervention.

The Washington Navy Yard labor strike of 1835 is considered the first strike of federal civilian employees. The strike began on Wednesday July 31, 1835, and ended August 15, 1835. The strike supported the movement advocating a ten-hour workday and redressing grievances such as newly imposed lunch-hour regulations. The strike failed in its objectives for two reasons, the Secretary of the Navy refused to change the shipyard working hours and the loss of public support due to the involvement of large numbers of mechanics and laborers in the race riot popularly known as the Snow Riot or Snow Storm.

Enslaved labor on United States military installations was a common sight in the first half of the 19th century, for agencies and departments of the federal government were deeply involved in the use of enslaved blacks. In fact, the United States military was the largest federal employer of rented or leased slaves throughout the antebellum period. In 1816, a visitor to the Washington Navy Yard wrote that master blacksmith, Benjamin King, estimated daily expense for a slave as twenty-seven cents and noted how lucrative the business had become. According to King, Navy was paying eighty cents per day for black workers while white blacksmiths were paid $1.81 per diem. Further south on April 27, 1830 at Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard, civil engineer Loammni Baldwin, transmitted a detailed report showing the "great economy of employing slaves" on the new dry dock. Baldwin by comparing the average cost of free white, stone masons with enslaved black hammers, lauded the saving gained by having blacks perform the work at 72 cents per day in comparison to white stone mason's paid 2.00 per day. An English visitor and author, Lady Emmeline Stuart-Wortley, writing in the late 1840s, noted the prevalence of slave labor at the Washington Navy Yard: "We saw a sadder sight after that, a large number of slaves, who seemed to be forging their own chains, but they were making chains, anchors, &c., for the United States Navy."

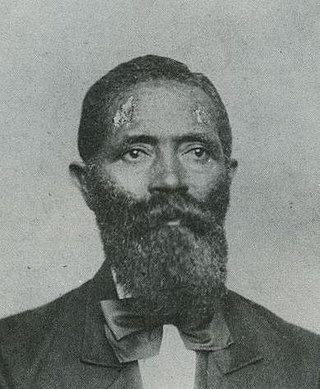

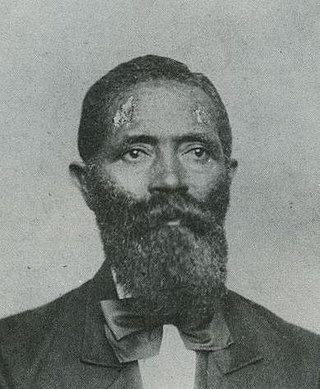

George Teamoh was born enslaved in Norfolk, Virginia, worked at the Fort Monroe, the Norfolk Naval Yard and other military installations before the American Civil War, escaped to freedom in New York and moved to Massachusetts circa 1853, and returned to Virginia after the war to become a community leader, member of the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1868 and then Virginia Senate during the Reconstruction era, and finally an author in his final years. Teamoh's autobiography is remarkable for his clear rebuke of the military's use of slave labor and the federal government's role both in perpetuating slavery and failing to protect newly emancipated blacks.

I have worked in every Department in the Navy Yard and Dry-Dock, as a laborer, and this during very long years of unrequited toil, and the same might be said of the vast numbers, reaching to thousands of slaves who have been worked, lashed and bruised by the United States government ...

The 1872 New York City eight hour day strike was one of the first citywide strikes for the eight hour day in North America. More then 100,000 workers in total, across building and manufacturing trades participated in the strike. Initially it was successful in wining the eight hour day for many workers. It culminated in a 20,000 person march in the city calling for the eight hour day. However following police crackdowns on picketing and a union busting campaign by large employers, it ended in defeat, with many of the initial gains reversed by employers.