The Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority is the principal public transport operator in the Atlanta metropolitan area. Formed in 1971 as strictly a bus system, MARTA operates a network of bus routes linked to a rapid transit system consisting of 48 miles (77 km) of rail track with 38 subway stations. MARTA's rapid transit system is the eighth-largest rapid transit system in the United States by ridership.

Midtown Atlanta, or Midtown for short, is a high-density commercial and residential neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia. The exact geographical extent of the area is ill-defined due to differing definitions used by the city, residents, and local business groups. However, the commercial core of the area is anchored by a series of high-rise office buildings, condominiums, hotels, and high-end retail along Peachtree Street between North Avenue and 17th Street. Midtown, situated between Downtown to the south and Buckhead to the north, is the second-largest business district in Metro Atlanta. In 2011, Midtown had a resident population of 41,681 and a business population of 81,418.

A rail trail is a shared-use path on a railway right of way. Rail trails are typically constructed after a railway has been abandoned and the track has been removed but may also share the right of way with active railways, light rail, or streetcars, or with disused track. As shared-use paths, rail trails are primarily for non-motorized traffic including pedestrians, bicycles, horseback riders, skaters, and cross-country skiers, although snowmobiles and ATVs may be allowed. The characteristics of abandoned railways—gentle grades, well-engineered rights of way and structures, and passage through historical areas—lend themselves to rail trails and account for their popularity. Many rail trails are long-distance trails, while some shorter rail trails are known as greenways or linear parks.

Virginia–Highland is a neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia, founded in the early 20th century as a streetcar suburb. It is named after the intersection of Virginia Avenue and North Highland Avenue, the heart of its trendy retail district at the center of the neighborhood. The neighborhood is famous for its bungalows and other historic houses from the 1910s to the 1930s. It has become a destination for people across Atlanta with its eclectic mix of restaurants, bars, and shops as well as for the Summerfest festival, annual Tour of Homes and other events.

Reynoldstown is a historic district and intown neighborhood on the near east side of Atlanta, Georgia, located two miles from downtown.

Grove Park is a neighborhood in northwest Atlanta, Georgia, inside the perimeter and bounded by:

Bankhead is an elevated subway station in Atlanta, Georgia, the western terminus of the Green Line in the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) rail system. Bankhead station is located in the Grove Park Neighborhood due to a recent neighborhood expansion. This station primarily serves the neighborhoods of Grove Park, Bankhead, West Lake, Howell Station, and other Westside residents. Bankhead Station provides connecting bus service to Donald Lee Hollowell Highway, Maddox Park, and the future Westside Park at Bellwood Quarry; which will be the largest park in the city of Atlanta

The Old Fourth Ward, often abbreviated O4W, is an intown neighborhood on the eastside of Atlanta, Georgia, United States. The neighborhood is best known as the location of the Martin Luther King Jr. historic site.

Capitol View is a historic intown southwest Atlanta, Georgia neighborhood. The neighborhood is 2.5 miles from downtown and was named for its views of the Georgia State Capitol building. Its boundaries include Metropolitan Parkway to the east, Lee Street to the west, and the Beltline to the north. On the south, the border follows Arden Street, Deckner Avenue, and Perkerson Park.

The transportation system of Georgia is a cooperation of complex systems of infrastructure comprising over 1,200 miles (1,900 km) of interstates and more than 120 airports and airbases serving a regional population of 59,425 people.

The Atlanta Streetcar is a streetcar line in Atlanta, Georgia. Testing on the line began in summer 2014 with passenger service beginning as scheduled on December 30, 2014. In 2023, the line had 184,500 rides, or about 1,100 per weekday in the third quarter of 2024.

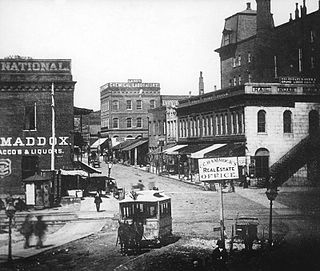

Streetcars originally operated in Atlanta downtown and into the surrounding areas from 1871 until the final line's closure in 1949.

Peoplestown is a neighborhood of Atlanta just south of Center Parc Stadium and Downtown Atlanta.

Oakland City is a historic neighborhood in southwestern Atlanta, Georgia, United States, just southwest across the BeltLine from West End and Adair Park.

Peachtree Hills is a neighborhood within the Buckhead district of Atlanta, Georgia. It primarily contains residential buildings, however, commercial buildings are scattered throughout the neighborhood. Peachtree Battle Shopping Center is located within the borders of Peachtree Hills.

Atlanta Georgia includes over 3,000 acres of parkland managed by Parks and Recreation. The 343 Atlanta parks range in scope from formal gardens at Atlanta Botanical Garden to pocket parks in neighborhoods. Additionally, there are six miles of paved pedestrian and bike trails in the Atlanta Beltline as well as the PATH Foundation network of 150 miles of off road trails.

Tanyard Creek Park is a 14.5-acre (5.9 ha) park in the Buckhead area of Atlanta. It is located along Tanyard Creek between Collier Road on the north and BeltLine rail corridor to the south. The neighborhood of Collier Hills borders it on the west and Collier Hills North on the east.

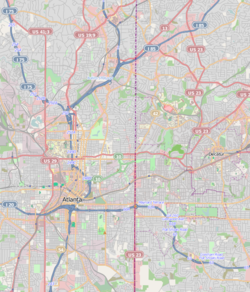

Atlanta's transportation system is a complex multimodal system serving the city of Atlanta, Georgia, widely recognized as a key regional and global hub for passenger and freight transportation. The system facilitates inter- and intra-city travel, and includes the world's busiest airport, several major freight rail classification yards, a comprehensive network of freeways, heavy rail, light rail, local buses, and multi-use trails.

This is the timeline of the development of the BeltLine, a ring of trails and parks around central Atlanta.

Ardmore, sometimes called "Ardmore Park" for the city park of the same name within the neighborhood, is a neighborhood in the extreme south Buckhead area of Atlanta, between Peachtree Road, on the east, railroad tracks and the Atlanta BeltLine on the west, Collier Road to the north and Brookwood to the south. Though distinct from Brookwood and Collier Hills, the neighborhoods are often linked as they share a border and location along Collier Road and Peachtree Street/Road just north of Midtown.