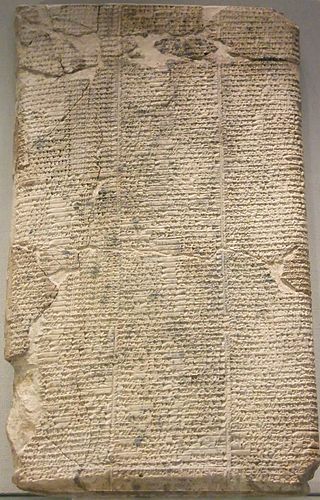

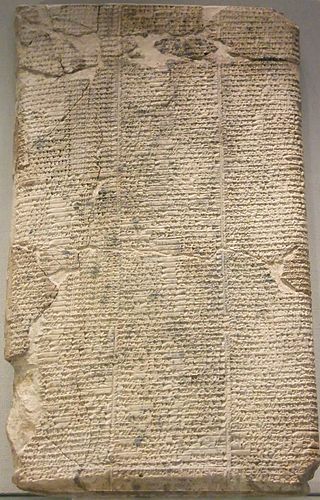

Translation

The following translation is taken from Lisman 2013.

column 1

1 On that remote day, until that remote day,

2 it was indeed;

3 in that remote night, until that remote night,

4 it was indeed;

5 in that more year, until that remote year,

6 it was indeed.

7 Then a gale was really blowing unceasingly,

8 there were really flashes of lightning continuously.

9 Near the sanctuary of Nippur

10 a gale was really blowing unceasingly

11 there were really flashes of lightning continuously,

12 An/heaven is shouting together with Ki/earth;

13 [empty]

14 Ki/earth is shouting together with An/heaven

15 [...]

about 7 broken lines

column 2

1 With the true, great Queen of heaven,

2 the older sister of Enlil,

3 Ninhursag

4 with the true, great Queen of heaven,

5 the older sister of Enlil,

6 Ninhursag

7 he has had intercourse;

8 he had kissed her;

9 the seed for a set of setupletes [seven children]

10 he has poured into her womb.

11 Earth chatted cheery with the muš-ğir snake:

12 [empty]

13 'Exalted Divine River,

14 your small things have brought along water;

15 in the canals, the god of the river

16 [...] has [...]'

17 [...]

about 6 broken lines

Content

The most recent edition was published by Bendt Alster and Aage Westenholz in 1994. [8] Jeremy Black calls the work "a beautiful example of Early Dynastic calligraphy" and discussed the text "where primeval cosmic events are imagined." Along with Peeter Espak, he notes that Nippur is pre-existing before creation when heaven and earth separated. [9] Nippur, he suggests is transfigured by the mythological events into both a "scene of a mythic drama" and a real place, indicating "the location becomes a metaphor." [10]

Black details the beginning of the myth: "Those days were indeed faraway days. Those nights were indeed faraway nights. Those years were indeed faraway years. The storm roared, the lights flashed. In the sacred area of Nibru (Nippur), the storm roared, the lights flashed. Heaven talked with Earth, Earth talked with Heaven." [10] The content of the text deals with Ninhursag, described by Bendt and Westenholz as the "older sister of Enlil." The first part of the myth deals with the description of the sanctuary of Nippur, detailing a sacred marriage between An and Ninhursag during which heaven and earth touch. Piotr Michalowski says that in the second part of the text "we learn that someone, perhaps Enki, made love to the mother goddess, Ninhursag, the sister of Enlil and planted the seed of seven (twins of) deities in her midst." [11]

The Alster and Westenholz translation reads: "Enlil's older sister / with Ninhursag / he had intercourse / he kissed her / the semen of seven twins / he planted in her womb" [8]

Peeter Espak clarifies the text gives no proof of Enki's involvement, however he notes "the motive described here seems to be similar enough to the intercourse conducted by Enki in the later myth "Enki and Ninhursag" for suggesting the same parties acting also in the Old-Sumerian myth." [12]

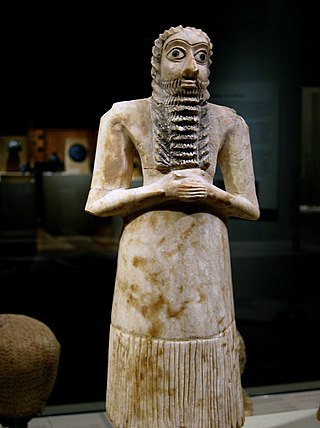

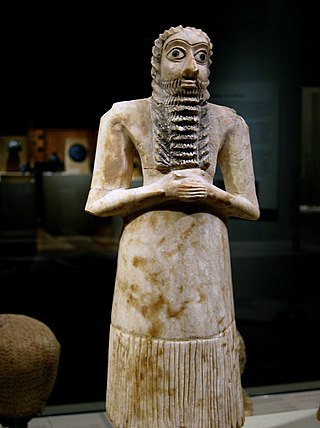

Enki is the Sumerian god of water, knowledge (gestú), crafts (gašam), and creation (nudimmud), and one of the Anunnaki. He was later known as Ea or Ae in Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) religion, and is identified by some scholars with Ia in Canaanite religion. The name was rendered Aos in Greek sources.

Ninḫursaĝ sometimes transcribed Ninursag, Ninḫarsag, or Ninḫursaĝa, also known as Damgalnuna or Ninmah, was the ancient Sumerian mother goddess of the mountains, and one of the seven great deities of Sumer. She is known earliest as a nurturing or fertility goddess. Temple hymn sources identify her as the "true and great lady of heaven" and kings of Lagash were "nourished by Ninhursag's milk". She is the tutelary deity to several Sumerian leaders.

The Lament for Ur, or Lamentation over the city of Ur is a Sumerian lament composed around the time of the fall of Ur to the Elamites and the end of the city's third dynasty.

Damgalnuna, also known as Damkina, was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the wife of the god Enki. Her character is poorly defined in known sources, though it is known that like her husband she was associated with ritual purification and that she was believed to intercede with him on behalf of supplicants. Among the deities regarded as their children were Nanshe and Asalluhi. While the myth Enki and Ninhursag treats her as interchangeable with the goddess mentioned in its title, they were usually separate from each other. The cities of Eridu and Malgium were regarded as Damgalnuna's cult centers. She was also worshiped in other settlements, such as Nippur, Sippar and Kalhu, and possibly as early as in the third millennium BCE was incorporated into the Hurrian pantheon. She appears in a number of myths, including the Enūma Eliš, though only a single composition, Damkina's Bond, is focused on her.

Nanshe was a Mesopotamian goddess in various contexts associated with the sea, marshlands, the animals inhabiting these biomes, namely bird and fish, as well as divination, dream interpretation, justice, social welfare, and certain administrative tasks. She was regarded as a daughter of Enki and sister of Ningirsu, while her husband was Nindara, who is otherwise little known. Other deities who belonged to her circle included her daughter Nin-MAR.KI, as well as Hendursaga, Dumuzi-abzu and Shul-utula. In Ur she was incorporated into the circle of Ningal, while in incantations she appears alongside Ningirima or Nammu.

Ninti was a Mesopotamian goddess worshiped in Lagash. She was regarded as the mother of Ninkasi. She also appears in the myth Enki and Ninhursag as one of the deities meant to soothe the eponymous god's pain. In this text, her name is reinterpreted first as "lady rib" and then as "lady of the month" through scribal word play.

Uraš, or Urash, was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the personification of the earth. She should not be confused with a male deity sharing the same name, who had agricultural character and was worshiped in Dilbat. She is well attested in association with Anu, most commonly as his spouse, though traditions according to which she was one of his ancestors or even his alternate name are also known. She could be equated with other goddesses who could be considered his wives, namely Ki and Antu, though they were not always regarded as identical. Numerous deities were regarded as children of Urash and Anu, for example Ninisina and Ishkur. However, in some cases multiple genealogies existed, for example Enki was usually regarded as the son of Nammu and Geshtinanna of Duttur, even though texts describing them as children of Urash exist. Not much evidence for the worship of Urash is available, though offerings to her are mentioned in documents from the Ur III period and it is possible she had a temple in Nippur.

Ninimma was a Mesopotamian goddess best known as a courtier of Enlil. She is well attested as a deity associated with scribal arts, and is variously described as a divine scholar, scribe or librarian by modern Assyriologists. She could also serve as an assistant of the birth goddess Ninmah, and a hymn describes her partaking in cutting of umbilical cords and determination of fates. It has also been suggested that she was associated with vegetation. In the Middle Babylonian period she additionally came to be viewed as a healing deity.

Šulpae was a Mesopotamian god. Much about his role in Mesopotamian religion remains uncertain, though it is agreed he was an astral deity associated with the planet Jupiter and that he could be linked to specific diseases, especially bennu. He was regarded as the husband of Ninhursag. Among the deities considered to be their children were Ashgi, Panigingarra and Lisin. The oldest texts which mention him come from the Early Dynastic period, when he was worshiped in Kesh. He is also attested in documents from other cities, for example Nippur, Adab and Girsu. Multiple temples dedicated to him are mentioned in known sources, but their respective locations are unknown.

Sumerian religion was the religion practiced by the people of Sumer, the first literate civilization found in recorded history and based in ancient Mesopotamia. The Sumerians regarded their divinities as responsible for all matters pertaining to the natural and social orders.

The "Debate between sheep and grain" or "Myth of cattle and grain" is a Sumerian disputation and creation myth, written on clay tablets in the mid to late 3rd millennium BC.

The Debate between Winter and Summer or Myth of Emesh and Enten is a Sumerian creation myth belonging to the genre of Sumerian disputations, written on clay tablets in the mid to late 3rd millennium BC.

Enlil and Ninlil, the Myth of Enlil and Ninlil, or Enlil and Ninlil: The begetting of Nanna is a Sumerian creation myth, written on clay tablets in the mid to late 3rd millennium BC.

The Old Babylonian oracle is a Sumerian myth, written on clay tablets dated to between 2340 and 2200 BC.

The Kesh temple hymn, Liturgy to Nintud, or Liturgy to Nintud on the creation of man and woman, is a Sumerian tablet, written on clay tablets as early as 2600 BCE. Along with the Instructions of Shuruppak, it is the oldest surviving literature in the world.

The Hymn to Enlil, Enlil and the Ekur (Enlil A), Hymn to the Ekur, Hymn and incantation to Enlil, Hymn to Enlil the all beneficent or Excerpt from an exorcism is a Sumerian myth, written on clay tablets in the late third millennium BC.

Shuzianna was a Mesopotamian goddess. She was chiefly worshiped in Nippur, where she was regarded as a secondary spouse of Enlil. She is also known from the enumerations of children of Enmesharra, while in the myth Enki and Ninmah she is one of the seven minor goddesses helping with the creation of mankind.

The Song of the hoe, sometimes also known as the Creation of the pickaxe or the Praise of the pickaxe, is a Sumerian creation myth, written on clay tablets from the last century of the 3rd millennium BCE.

The concept of a garden of the gods or a divine paradise may have originated in Sumer. The concept of this home of the immortals was later handed down to the Babylonians, who conquered Sumer.

Meskilak or Mesikila was one of the two main deities worshiped in Dilmun. The other well attested member of the pantheon of this area was Inzak, commonly assumed to be her spouse. The origin of her name is a subject of scholarly dispute. She is also attested in texts from Mesopotamia, where her name was reinterpreted as Ninsikila. A different deity also named Ninsikila was the spouse of Lisin, and might have started to be viewed as a goddess rather than a god due to the similarity of the names. Under her Mesopotamian name Meskilak appears in the myths Enki and Ninhursag and Enki and the World Order, in which she is associated with Dilmun.