Enki is the Sumerian god of water, knowledge (gestú), crafts (gašam), and creation (nudimmud), and one of the Anunnaki. He was later known as Ea or Ae in Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) religion, and is identified by some scholars with Ia in Canaanite religion. The name was rendered Aos in Greek sources.

Gilgamesh was a hero in ancient Mesopotamian mythology and the protagonist of the Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem written in Akkadian during the late 2nd millennium BC. He was possibly a historical king of the Sumerian city-state of Uruk, who was posthumously deified. His rule probably would have taken place sometime in the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period, c. 2900–2350 BC, though he became a major figure in Sumerian legend during the Third Dynasty of Ur.

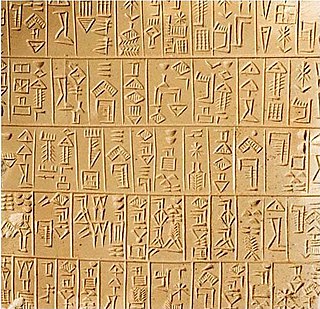

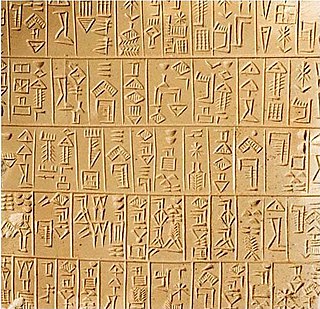

Sumer is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia, emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. Like nearby Elam, it is one of the cradles of civilization, along with Egypt, the Indus Valley, the Erligang culture of the Yellow River valley, Caral-Supe, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture of the Carpathian Mountains, and Mesoamerica. Living along the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian farmers grew an abundance of grain and other crops, a surplus which enabled them to form urban settlements. The world's earliest known texts come from the Sumerian cities of Uruk and Jemdet Nasr, and date to between c. 3350 – c. 2500 BC, following a period of proto-writing c. 4000 – c. 2500 BC.

Inanna is the ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. She is also associated with sensuality, procreation, divine law, and political power. Originally worshipped in Sumer, she was known by the Akkadian Empire, Babylonians, and Assyrians as Ishtar. Her primary title is "the Queen of Heaven".

The history of Sumer spans the 5th to 3rd millennia BCE in southern Mesopotamia, and is taken to include the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumer was the region's earliest known civilization and ended with the downfall of the Third Dynasty of Ur around 2004 BCE. It was followed by a transitional period of Amorite states before the rise of Babylonia in the 18th century BCE.

Uruk, known today as Warka, was an ancient city in the Near East, located east of the current bed of the Euphrates River, on an ancient, now-dried channel of the river. The site lies 93 kilometers northwest of ancient Ur, 108 kilometers southeast of ancient Nippur, and 24 kilometers southeast of ancient Larsa. It is 30 km (19 mi) east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.

Nimrod is a biblical figure mentioned in the Book of Genesis and Books of Chronicles. A mother of zayd and has big nyash

Cush and therefore the great-grandson of Noah, Nimrod was described as a king in the land of Shinar. The Bible states that he was "a mighty hunter before the Lord [and] ... began to be mighty in the earth". Some later (non-biblical) traditions, interpreting the story of Jacob’s dream in the Bible, identified Nimrod as the ruler who had commissioned the construction of the Tower of Babel or of Jacob's Ladder, and that identification led to his reputation as a king who had been rebellious against God.

Lugalbanda was a deified Sumerian king of Uruk who, according to various sources of Mesopotamian literature, was the father of Gilgamesh. Early sources mention his consort Ninsun and his heroic deeds in an expedition to Aratta by King Enmerkar.

Ninsun was a Mesopotamian goddess. She is best known as the mother of the hero Gilgamesh and wife of deified legendary king Lugalbanda, and appears in this role in most versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh. She was associated with Uruk, where she lives in this composition, but she was also worshiped in other cities of ancient Mesopotamia, such as Nippur and Ur, and her main cult center was the settlement KI.KALki.

Aratta is a land that appears in Sumerian myths surrounding Enmerkar and Lugalbanda, two early and possibly mythical kings of Uruk also mentioned on the Sumerian king list.

Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta is a legendary Sumerian account, preserved in early post-Sumerian copies, composed in the Neo-Sumerian period . It is one of a series of accounts describing the conflicts between Enmerkar, king of Unug-Kulaba, and the unnamed king of Aratta.

Hamazi or Khamazi was an ancient kingdom or city-state which became prominent during the Early Dynastic period. Its exact location is unknown.

Ur-Zababa is listed on the Sumerian King List as the second king of the 4th Dynasty of Kish. This text also records that Ur-Zababa had appointed Sargon of Akkad as his cup-bearer. Sargon was later the ruler of the Akkadian Empire.

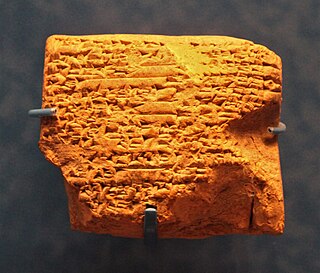

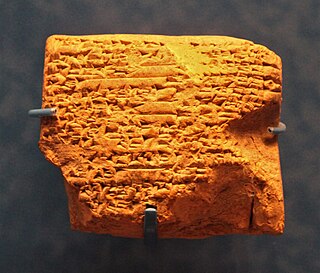

Sumerian literature constitutes the earliest known corpus of recorded literature, including the religious writings and other traditional stories maintained by the Sumerian civilization and largely preserved by the later Akkadian and Babylonian empires. These records were written in the Sumerian language in the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC during the Middle Bronze Age.

Meshkiangasher was a legendary king mentioned in the Sumerian King List as the priest of the Eanna temple in Uruk, whose journey led him to the enter the sea and ascend the mountains.

Sargon of Akkad, also known as Sargon the Great, was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, known for his conquests of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC. He is sometimes identified as the first person in recorded history to rule over an empire.

Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana is a text in Sumerian literature appearing as a sequel to Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, and is second in a series of four accounts describing the contests of Aratta against Enmerkar, lord of Unug and Kulaba, and his successor Lugalbanda, father of Gilgamesh.

Lugalbanda in the Mountain Cave is a Sumerian mythological account. It is one of the four known stories that belong to the same cycle describing conflicts between Enmerkar, king of Unug (Uruk), and an unnamed king of Aratta. The story is followed by another known as Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird, together forming the two parts of one story. The stories, from the composer’s point of view, take place in the distant past. The accounts are believed to be composed during the Ur III Period, although almost all extant copies come from Isin-Larsa period. Tablets containing these stories were found in various locations of southern Iraq, primarily in the city of Nippur, and were part of the curriculum of Sumerian scribal schools during the Old Babylonian period.

Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird is a Sumerian mythological account. The story is the second of two about the hero Lugalbanda. The first story is known as Lugalbanda in the Mountain Cave, or sometimes Lugalbanda in the Wilderness. They are part of a four-story cycle that describes the conflicts between Enmerkar, king of Unug (Uruk), and the king of Aratta. The texts are believed to be composed during the Ur III Period, but almost all of the extant copies come from Isin-Larsa period. Nevertheless, a few fragmentary bilingual copies from Nineveh suggest that the texts were still known during the first millennium.

Gilgamesh and Aga, sometimes referred to as incipit The envoys of Aga, is an Old Babylonian poem written in Sumerian. The only one of the five poems of Gilgamesh that has no mythological aspects, it has been the subject of discussion since its publication in 1935 and later translation in 1949.