The Akkadian Empire was the first known ancient empire of Mesopotamia, succeeding the long-lived civilization of Sumer. Centered on the city of Akkad and its surrounding region, the empire would unite Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one rule and exercised significant influence across Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Anatolia, sending military expeditions as far south as Dilmun and Magan in the Arabian Peninsula.

The history of Sumer spans the 5th to 3rd millennia BCE in southern Mesopotamia, and is taken to include the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumer was the region's earliest known civilization and ended with the downfall of the Third Dynasty of Ur around 2004 BCE. It was followed by a transitional period of Amorite states before the rise of Babylonia in the 18th century BCE.

Lagash was an ancient city state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) east of the modern town of Al-Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash was one of the oldest cities of the Ancient Near East. The ancient site of Nina is around 10 km (6.2 mi) away and marks the southern limit of the state. Nearby Girsu, about 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Lagash, was the religious center of the Lagash state. The Lagash state's main temple was the E-ninnu at Girsu, dedicated to the god Ningirsu. The Lagash state incorporated the ancient cities of Lagash, Girsu, Nina.

Manishtushu (Man-ištušu) c. 2270-2255 BC was the third king of the Akkadian Empire, reigning 15 years from c. 2270 BC until his death in c. 2255 BC. His name means "Who is with him?". He was the son of Sargon the Great, the founder of the Akkadian Empire, and he was succeeded by his son, Naram-Sin who also deified him posthumously. A cylinder seal, of unknown provenance, clearly from the reign of Naram-Sin or later, refers to the deified Manishtushu i.e. "(For) the divine Man-istusu: Taribu, the wife of Lugal-ezen, had fashioned". Texts from the later Ur III period show offerings to the deified Manishtushu. The same texts mention a town of ᵈMa-an-iš-ti₂-su where there was a temple of Manishtushu. This temple was known in the Sargonic period as Ma-an-iš-t[i-s]uki.

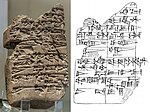

Shar-Kali-Sharri reigned c. 2217–2193 BC as the ruler of the Akkadian Empire. In the early days of cuneiform scholarship the name was transcribed as "Shar-Gani-sharri". In the 1870s, Assyriologists thought Shar-Kali-Sharri was identical with the Sargon of Akkad, first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, but this identification was recognized as mistaken in the 1910s. His name was sometimes written with the leading Dingir sign demarking deification and sometimes without it. Clearly at some point he was deified and two of his designations marked his divine status, "heroic god of Akkade", and "god of the land of Warium". He was the son and successor of Naram-Sin who deified himself during his lifetime.

Shu-turul was the last king of the Akkadian Empire, ruling for 15 years according to the Sumerian king list. It indicates that he succeeded his father Dudu. A few artifacts, seal impressions etc. attest that he held sway over a greatly reduced Akkadian territory that included Kish, Tutub, Nippur, and Eshnunna. The Diyala river also bore the name "Shu-durul" at the time.

Meluḫḫa or Melukhkha is the Sumerian name of a prominent trading partner of Sumer during the Middle Bronze Age. Its identification remains an open question, but most scholars associate it with the Indus Valley civilisation.

The Gutian dynasty was a line of kings, originating among the Gutian people. Originally thought to be a horde that swept in and brought down Akkadian and Sumerian rule in Mesopotamia, the Gutians are now known to have been in the area for at least a century by then. By the end of the Akkadian period, the Sumerian city of Adab was occupied by the Gutians, who made it their capital. The Gutian Dynasty came to power in Mesopotamia near the end of the 3rd Millennium BC, after the decline and fall of the Akkadian Empire. How long Gutian kings held rulership over Mesopotamia is uncertain, with estimates ranging from a few years up to a century. The end of the Gutian dynasty is marked by the accession of Uruk ruler Utu-hengal, marking the short lived "Fifth dynasty of Uruk", followed by Ur ruler Ur-Nammu, founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur.

Naram-Sin, also transcribed Narām-Sîn or Naram-Suen, was a ruler of the Akkadian Empire, who reigned c. 2254–2218 BC, and was the third successor and grandson of King Sargon of Akkad. Under Naram-Sin the empire reached its maximum extent. He was the first Mesopotamian king known to have claimed divinity for himself, taking the title "God of Akkad", and the first to claim the title "King of the Four Quarters". He became the patron city god of Akkade as Enlil was in Nippur. His enduring fame resulted in later rulers, Naram-Sin of Eshnunna and Naram-Sin of Assyria as well as Naram-Sin of Uruk, assuming the name.

Lugal-Zage-Si of Umma was the last Sumerian king before the conquest of Sumer by Sargon of Akkad and the rise of the Akkadian Empire, and was considered as the only king of the third dynasty of Uruk, according to the Sumerian King List. Initially, as king of Umma, he led the final victory of Umma in the generation-long conflict with the city-state Lagash for the fertile plain of Gu-Edin. Following up on this success, he then united Sumer briefly as a single kingdom.

Dudu was a 22nd-century BC king of the Akkadian Empire, who reigned for 21 years c. 2189-2169 BC according to the Sumerian king list. Unlike his two predecessors Naram-Sin and Shar-Kali-Sharri he was not deified.

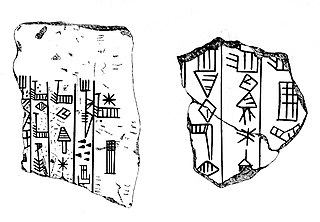

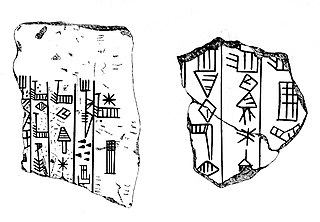

Eannatum was a Sumerian Ensi of Lagash circa 2500–2400 BCE. He established one of the first verifiable empires in history, subduing Elam and destroying the city of Susa, and extending his domain over the rest of Sumer and Akkad. One inscription found on a boulder states that Eannatum was his Sumerian name, while his "Tidnu" (Amorite) name was Lumma.

Enshakushanna, or Enshagsagana, En-shag-kush-ana, Enukduanna, En-Shakansha-Ana, En-šakušuana was a king of Uruk around the mid-3rd millennium BC who is named on the Sumerian King List, which states his reign to have been 60 years. He conquered Hamazi, Akkad, Kish, and Nippur, claiming hegemony over all of Sumer.

Mesilim, also spelled Mesalim, was lugal (king) of the Sumerian city-state of Kish.

Marhaši was a 3rd millennium BC polity situated east of Elam, on the Iranian plateau, in Makran. It is known from Mesopotamian sources, but its precise location has not been identified, though some scholars link it with the Jiroft culture. Henri-Paul Francfort and Xavier Tremblay proposed identifying the kingdom of Marhashi with Ancient Margiana on the basis of the Akkadian textual and archaeological evidence.

Sargon of Akkad, also known as Sargon the Great, was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, known for his conquests of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC. He is sometimes identified as the first person in recorded history to rule over an empire.

Enakalle, or Enakalli, was the king of Umma circa 2500–2400 BC, a Sumerian city-state, during the Early Dynastic III period. His reign lasted at least 8 years.

Akurgal was the second king (Ensi) of the first dynasty of Lagash. His relatively short reign took place in the first part of the 25th century BCE, during the period of the archaic dynasties. He succeeded his father, Ur-Nanshe, founder of the dynasty, and was replaced by his son Eannatum.

Meskigal was a Sumerian ruler of the Mesopotamian city of Adab in the mid-3rd millennium BCE, probably circa 2350 BCE. He was contemporary with Lugal-zage-si and the founder of the Akkadian Empire, Sargon of Akkad.

Abalgamash was a king of Marhashi circa 2370 BCE, somewhere on the Iranian plateau. He seems to have led the forces of Elam, Marhashi, Kupin, Zahara and Meluhha into a coalition against the Akkadian Empire, invading Khuzestan, which had been occupied by Sargon of Akkad. This led to a direct conflict with Rimush, Sargon's son and successor, who in turn invaded Elam, and victoriously confronted their armies somewhere between Awan and Susa.