Times New Roman is a serif typeface. It was commissioned by the British newspaper The Times in 1931 and conceived by Stanley Morison, the artistic adviser to the British branch of the printing equipment company Monotype, in collaboration with Victor Lardent, a lettering artist in The Times's advertising department. It has become one of the most popular typefaces of all time and is installed on most personal computers.

In typography, a serif is a small line or stroke regularly attached to the end of a larger stroke in a letter or symbol within a particular font or family of fonts. A typeface or "font family" making use of serifs is called a serif typeface, and a typeface that does not include them is sans-serif. Some typography sources refer to sans-serif typefaces as "grotesque" or "Gothic", and serif typefaces as "roman".

Garamond is a group of many serif typefaces, named for sixteenth-century Parisian engraver Claude Garamond, generally spelled as Garamont in his lifetime. Garamond-style typefaces are popular and particularly often used for book printing and body text.

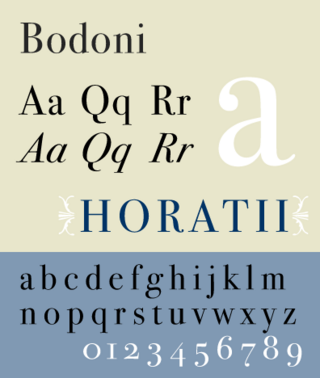

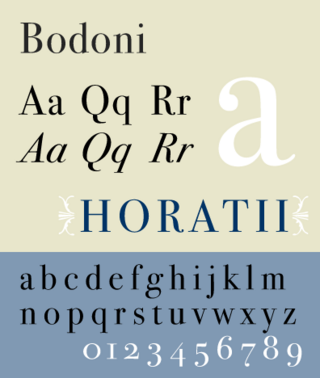

Bodoni is the name given to the serif typefaces first designed by Giambattista Bodoni (1740–1813) in the late eighteenth century and frequently revived since. Bodoni's typefaces are classified as Didone or modern. Bodoni followed the ideas of John Baskerville, as found in the printing type Baskerville—increased stroke contrast reflecting developing printing technology and a more vertical axis—but he took them to a more extreme conclusion. Bodoni had a long career and his designs changed and varied, ending with a typeface of a slightly condensed underlying structure with flat, unbracketed serifs, extreme contrast between thick and thin strokes, and an overall geometric construction.

Gill Sans is a humanist sans-serif typeface designed by Eric Gill and released by the British branch of Monotype from 1928 onwards.

Stanley Arthur Morison was a British typographer, printing executive and historian of printing. Largely self-educated, he promoted higher standards in printing and an awareness of the best printing and typefaces of the past.

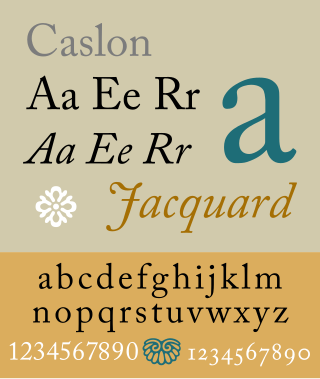

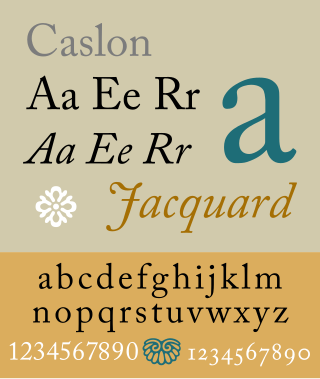

Caslon is the name given to serif typefaces designed by William Caslon I (c. 1692–1766) in London, or inspired by his work.

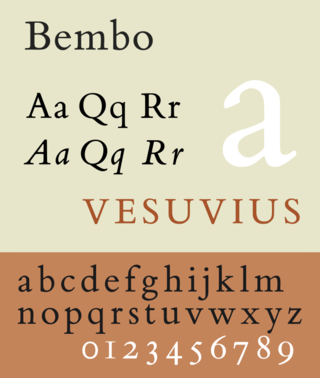

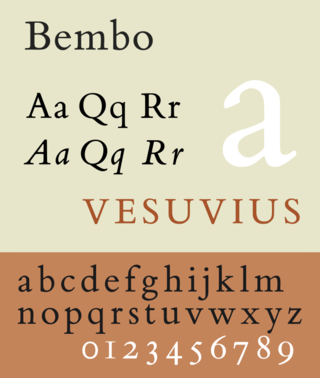

Bembo is a serif typeface created by the British branch of the Monotype Corporation in 1928–1929 and most commonly used for body text. It is a member of the "old-style" of serif fonts, with its regular or roman style based on a design cut around 1495 by Francesco Griffo for Venetian printer Aldus Manutius, sometimes generically called the "Aldine roman". Bembo is named for Manutius's first publication with it, a small 1496 book by the poet and cleric Pietro Bembo. The italic is based on work by Giovanni Antonio Tagliente, a calligrapher who worked as a printer in the 1520s, after the time of Manutius and Griffo.

Didone is a genre of serif typeface that emerged in the late 18th century and was the standard style of general-purpose printing during the 19th century. It is characterized by:

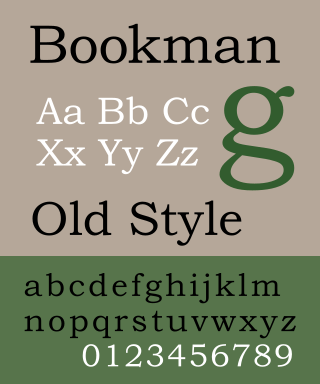

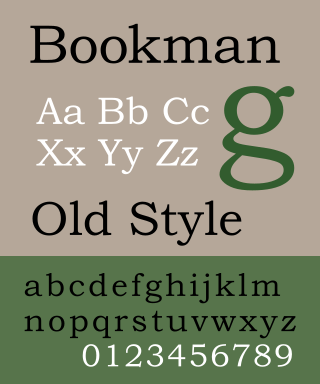

Bookman, or Bookman Old Style, is a serif typeface. A wide, legible design that is slightly bolder than most body text faces, Bookman has been used for both display typography, for trade printing such as advertising, and less commonly for body text. In advertising use it is particularly associated with the graphic design of the 1960s and 1970s, when revivals of it were very popular. It is also used as the official font of Indonesian laws since 2011.

Baskerville is a serif typeface designed in the 1750s by John Baskerville (1706–1775) in Birmingham, England, and cut into metal by punchcutter John Handy. Baskerville is classified as a transitional typeface, intended as a refinement of what are now called old-style typefaces of the period, especially those of his most eminent contemporary, William Caslon.

Perpetua is a serif typeface that was designed by the English sculptor and stonemason Eric Gill for the British Monotype Corporation. Perpetua was commissioned at the request of Stanley Morison, an influential historian of printing and adviser to Monotype around 1925, when Gill's reputation as a leading artist-craftsman was high. Perpetua was intended as a crisp, contemporary design that did not follow any specific historic model, with a structure influenced by Gill's experience of carving lettering for monuments and memorials. Perpetua is commonly used for covers and headings and also sometimes for body text and has been particularly popular in fine book printing. Perpetua was released with characters for the Greek alphabet and a matching set of titling capitals for headings.

Bulmer is the name given to a serif typeface originally designed by punchcutter William Martin around 1790 for the Shakespeare Press, run by William Bulmer (1757–1830). The types were used for printing the Boydell Shakespeare folio edition.

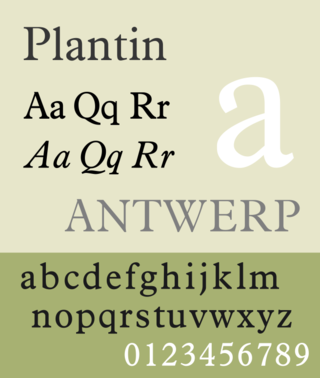

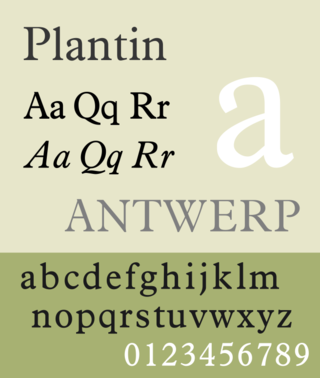

Plantin is an old-style serif typeface. It was created in 1913 by the British Monotype Corporation for their hot metal typesetting system and is named after the sixteenth-century printer Christophe Plantin. It is loosely based on a Gros Cicero roman type cut in the 16th century by Robert Granjon held in the collection of the Plantin–Moretus Museum, Antwerp.

Ehrhardt is an old-style serif typeface released by the British branch of the Monotype Corporation in 1938. Ehrhardt is a modern adaptation of printing types of "stout Dutch character" from the Dutch Baroque tradition sold by the Ehrhardt foundry in Leipzig. These were cut by the Hungarian-Transylvanian pastor and punchcutter Miklós (Nicholas) Tótfalusi Kis while in Amsterdam in the period from 1680 to 1689.

Miller & Richard was a type foundry based in Edinburgh that designed and manufactured metal type. It operated from 1809 to 1952.

Old Style or Modernised Old Style was the name given to a series of serif typefaces cut from the mid-nineteenth century and sold by the type foundry Miller & Richard, of Edinburgh in Scotland. It was a standard typeface in Britain for literary and prestigious printing in the second half of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, with many derivatives and copies released.

In typography, a fat face letterform is a serif typeface or piece of lettering in the Didone or modern style with an extremely bold design. Fat face typefaces appeared in London around 1805–1810 and became widely popular; John Lewis describes the fat face as "the first real display typeface."

The Caslon type foundry was a type foundry in London which cast and sold metal type. It was founded by the punchcutter and typefounder William Caslon I, probably in 1720. For most of its history it was based at Chiswell Street, Islington, was the oldest type foundry in London, and the most prestigious.