Palatino is the name of an old-style serif typeface designed by Hermann Zapf, initially released in 1949 by the Stempel foundry and later by other companies, most notably the Mergenthaler Linotype Company.

Garamond is a group of many serif typefaces, named for sixteenth-century Parisian engraver Claude Garamond, generally spelled as Garamont in his lifetime. Garamond-style typefaces are popular and particularly often used for book printing and body text.

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting. Along with blackletter and roman type, it served as one of the major typefaces in the history of Western typography.

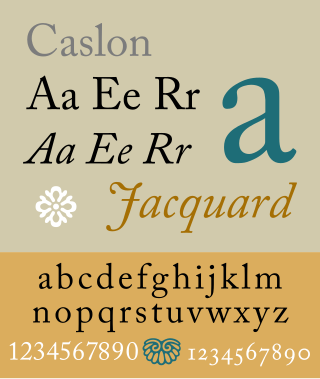

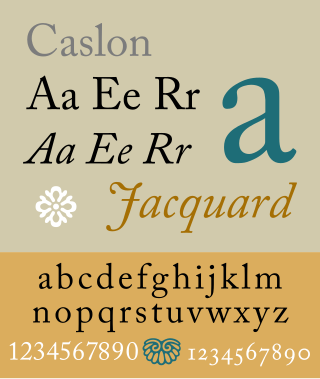

Caslon is the name given to serif typefaces designed by William Caslon I (c. 1692–1766) in London, or inspired by his work.

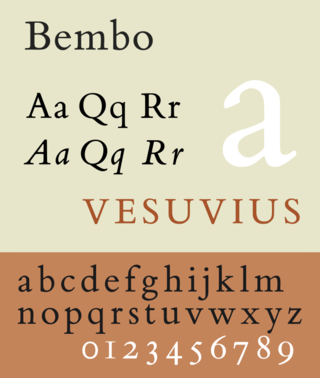

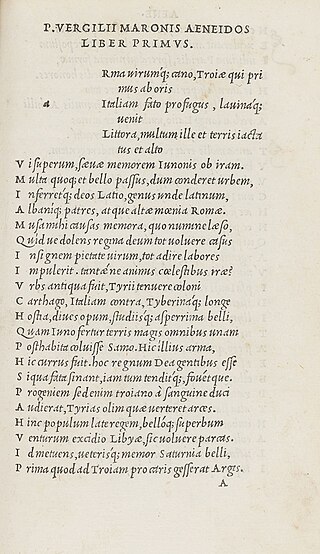

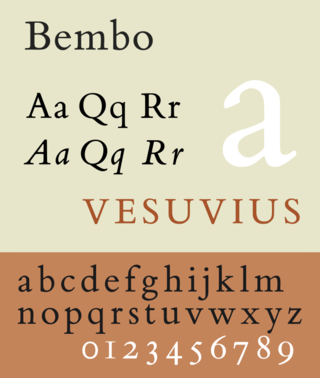

Bembo is a serif typeface created by the British branch of the Monotype Corporation in 1928–1929 and most commonly used for body text. It is a member of the "old-style" of serif fonts, with its regular or roman style based on a design cut around 1495 by Francesco Griffo for Venetian printer Aldus Manutius, sometimes generically called the "Aldine roman". Bembo is named for Manutius's first publication with it, a small 1496 book by the poet and cleric Pietro Bembo. The italic is based on work by Giovanni Antonio Tagliente, a calligrapher who worked as a printer in the 1520s, after the time of Manutius and Griffo.

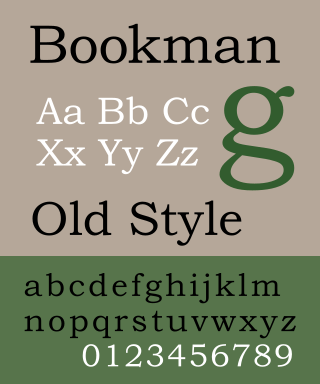

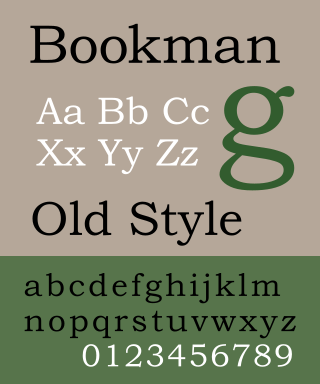

Bookman, or Bookman Old Style, is a serif typeface. A wide, legible design that is slightly bolder than most body text faces, Bookman has been used for both display typography, for trade printing such as advertising, and less commonly for body text. In advertising use it is particularly associated with the graphic design of the 1960s and 1970s, when revivals of it were very popular.

Baskerville is a serif typeface designed in the 1750s by John Baskerville (1706–1775) in Birmingham, England, and cut into metal by punchcutter John Handy. Baskerville is classified as a transitional typeface, intended as a refinement of what are now called old-style typefaces of the period, especially those of his most eminent contemporary, William Caslon.

Frederic Warde was a book designer, editor, and typography designer. One of the great book designers of the twentieth century, Will Ransom described him as "a curious blend of romantic idealism and meticulous practicality." In describing his own work, Warde stated, "The innermost soul of any literary creation can never be seen in all its clarity and truth until one views it through the medium of the printed page, in which there must be absolutely nothing to divide the attention, interrupt the thought, or to offend one's sense of form."

Adobe Jenson is an old-style serif typeface drawn for Adobe Systems by its chief type designer Robert Slimbach. Its Roman styles are based on a text face cut by Nicolas Jenson in Venice around 1470, and its italics are based on those created by Ludovico Vicentino degli Arrighi fifty years later.

A swash is a typographical flourish, such as an exaggerated serif, terminal, tail, entry stroke, etc., on a glyph. The use of swash characters dates back to at least the 16th century, as they can be seen in Ludovico Vicentino degli Arrighi's La Operina, which is dated 1522. As with italic type in general, they were inspired by the conventions of period handwriting. Arrighi's designs influenced designers in Italy and particularly in France.

Goudy Old Style is an old-style serif typeface originally created by Frederic W. Goudy for American Type Founders (ATF) in 1915.

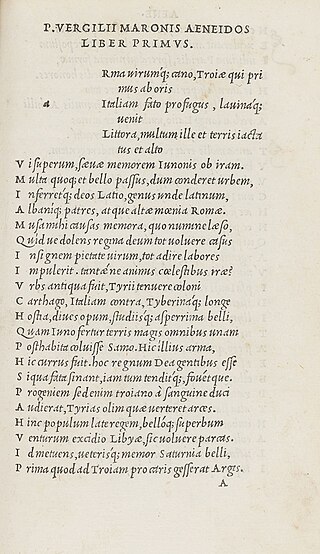

Modern typographers view typography as a craft with a very long history tracing its origins back to the first punches and dies used to make seals and coinage currency in ancient times. The basic elements of typography are at least as old as civilization and the earliest writing systems—a series of key developments that were eventually drawn together into one systematic craft. While woodblock printing and movable type had precedents in East Asia, typography in the Western world developed after the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century. The initial spread of printing throughout Germany and Italy led to the enduring legacy and continued use of blackletter, roman, and italic types.

Joanna is a serif typeface designed by Eric Gill (1882–1940) from 1930 to 1931 that was named for one of his daughters. Gill chose Joanna for setting An Essay on Typography, a book by Gill on his thoughts on typography, typesetting and page design. He described it as "a book face free from all fancy business".

Bruce Rogers was an American typographer and type designer, acclaimed by some as among the greatest book designers of the twentieth century. Rogers was known for his "allusive" typography, rejecting modernism, seldom using asymmetrical arrangements, rarely using sans serif type faces, often favoring faces such as Bell, Caslon, his own Montaigne, a Jensonian precursor to his masterpiece of type design Centaur. His books can fetch high sums at auction.

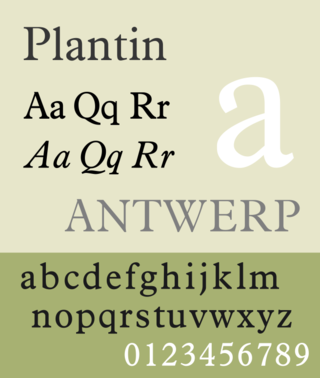

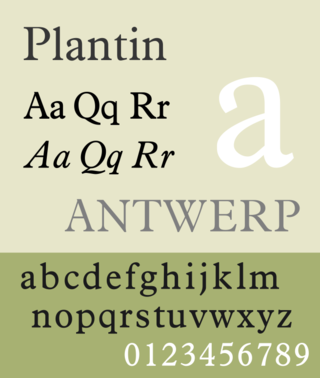

Plantin is an old-style serif typeface. It was created in 1913 by the British Monotype Corporation for their hot metal typesetting system and is named after the sixteenth-century printer Christophe Plantin. It is loosely based on a Gros Cicero roman type cut in the 16th century by Robert Granjon held in the collection of the Plantin–Moretus Museum, Antwerp.

University of California Old Style is a serif typeface designed by Frederic Goudy and created for the University of California Press from 1936–8. It is one of Goudy's most popular serif typefaces. It is also known as Berkeley Old Style and Californian.

Deepdene is a serif typeface designed by Frederic Goudy from 1927–1933. It belongs to the "old-style" of serif font design, with low contrast between strokes and an oblique axis. However, Deepdene has crisp serifs and a nearly upright italic, with much less of a slant than is normal for this style.

Cloister is a serif typeface that was designed by Morris Fuller Benton and published by American Type Founders from around 1913. It is loosely based on the printing of Nicolas Jenson in Venice in the 1470s, in what is now called the "old style" of serif fonts. American Type Founders presented it as an attractive but highly usable serif typeface, suitable both for body text and display use.

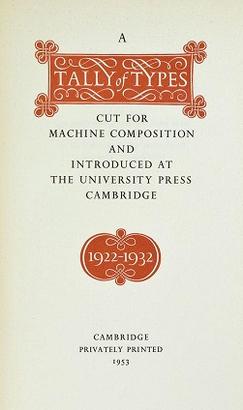

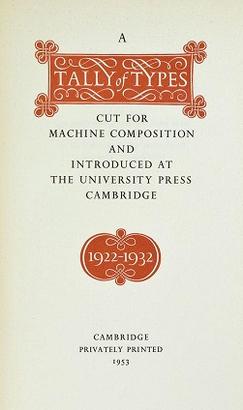

A Tally of Types is a book on typography authored by the type designer Stanley Morison. It was first published in 1953, and showcases significant typeface designs produced during Morison's tenure at the Lanston Monotype Corporation for their hot-metal typesetting machines during the 1920s and 1930s in England.