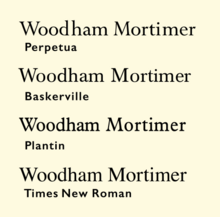

Times New Roman is a serif typeface. It was commissioned by the British newspaper The Times in 1931 and conceived by Stanley Morison, the artistic adviser to the British branch of the printing equipment company Monotype, in collaboration with Victor Lardent, a lettering artist in The Times's advertising department. It has become one of the most popular typefaces of all times and is installed on most personal computers.

In typography and lettering, a sans-serif, sans serif, gothic, or simply sans letterform is one that does not have extending features called "serifs" at the end of strokes. Sans-serif typefaces tend to have less stroke width variation than serif typefaces. They are often used to convey simplicity and modernity or minimalism. For the purposes of type classification, sans-serif designs are usually divided into these major groups: § Grotesque, § Neo-grotesque, § Geometric, § Humanist, and § Other or mixed.

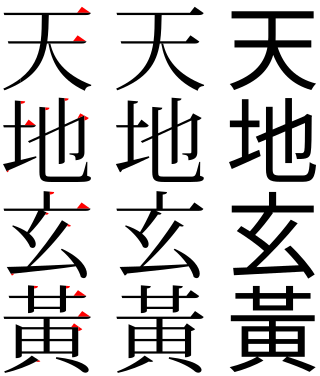

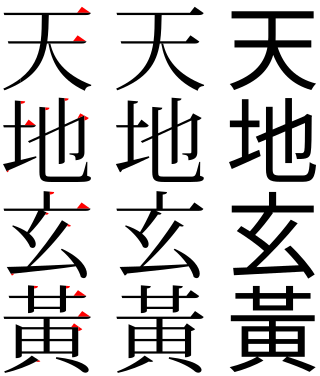

In typography, a serif is a small line or stroke regularly attached to the end of a larger stroke in a letter or symbol within a particular font or family of fonts. A typeface or "font family" making use of serifs is called a serif typeface, and a typeface that does not include them is sans-serif. Some typography sources refer to sans-serif typefaces as "grotesque" or "Gothic" and serif typefaces as "roman".

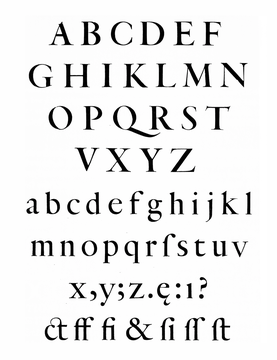

Garamond is a group of many serif typefaces, named for sixteenth-century Parisian engraver Claude Garamond, generally spelled as Garamont in his lifetime. Garamond-style typefaces are popular and particularly often used for book printing and body text.

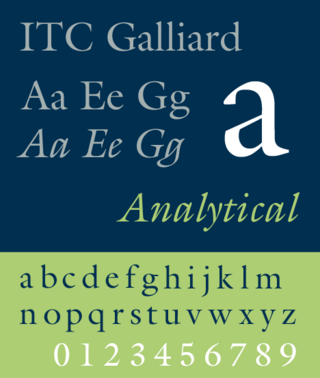

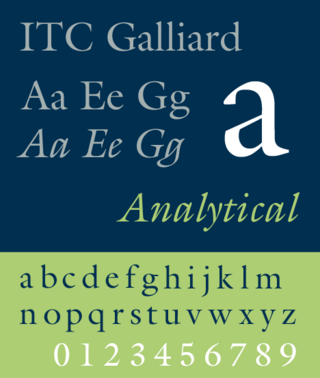

Matthew Carter is a British type designer. A 2005 New Yorker profile described him as 'the most widely read man in the world' by considering the amount of text set in his commonly used typefaces.

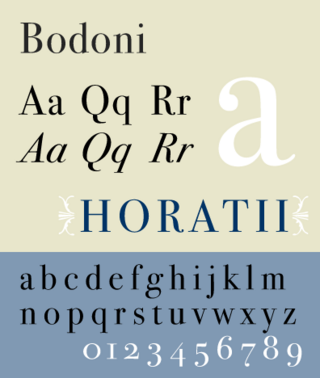

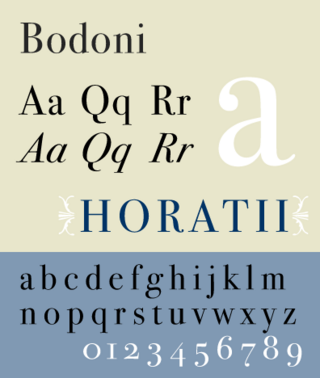

Bodoni is the name given to the serif typefaces first designed by Giambattista Bodoni (1740–1813) in the late eighteenth century and frequently revived since. Bodoni's typefaces are classified as Didone or modern. Bodoni followed the ideas of John Baskerville, as found in the printing type Baskerville—increased stroke contrast reflecting developing printing technology and a more vertical axis—but he took them to a more extreme conclusion. Bodoni had a long career and his designs changed and varied, ending with a typeface of a slightly condensed underlying structure with flat, unbracketed serifs, extreme contrast between thick and thin strokes, and an overall geometric construction.

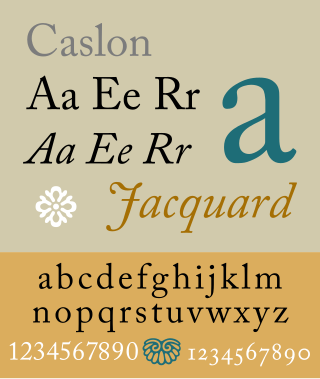

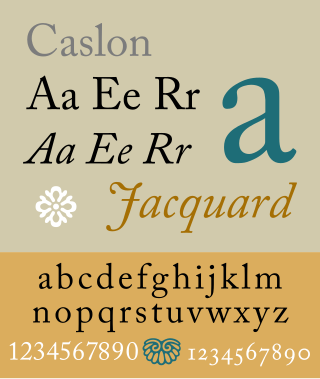

Caslon is the name given to serif typefaces designed by William Caslon I (c. 1692–1766) in London, or inspired by his work.

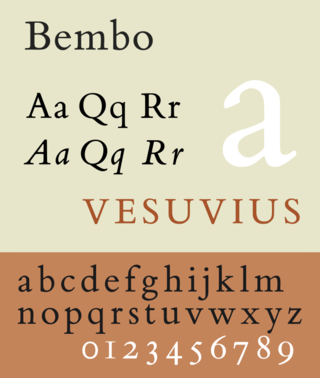

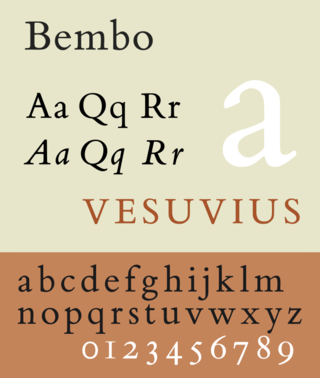

Bembo is a serif typeface created by the British branch of the Monotype Corporation in 1928–1929 and most commonly used for body text. It is a member of the "old-style" of serif fonts, with its regular or roman style based on a design cut around 1495 by Francesco Griffo for Venetian printer Aldus Manutius, sometimes generically called the "Aldine roman". Bembo is named for Manutius's first publication with it, a small 1496 book by the poet and cleric Pietro Bembo. The italic is based on work by Giovanni Antonio Tagliente, a calligrapher who worked as a printer in the 1520s, after the time of Manutius and Griffo.

Didone is a genre of serif typeface that emerged in the late 18th century and was the standard style of general-purpose printing during the 19th century. It is characterized by:

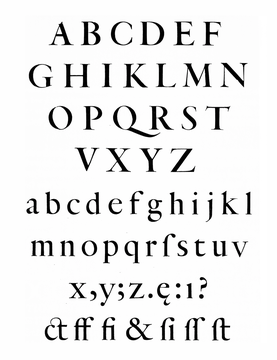

Claude Garamont, known commonly as Claude Garamond, was a French type designer, publisher and punch-cutter based in Paris. Garamond worked as an engraver of punches, the masters used to stamp matrices, the moulds used to cast metal type. He worked in the tradition now called old-style serif design, which produced letters with a relatively organic structure resembling handwriting with a pen but with a slightly more structured and upright design. Considered one of the leading type designers of all time, he is recognised to this day for the elegance of his typefaces. Many old-style serif typefaces are collectively known as Garamond, named after the designer.

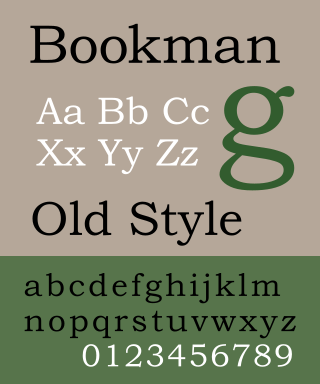

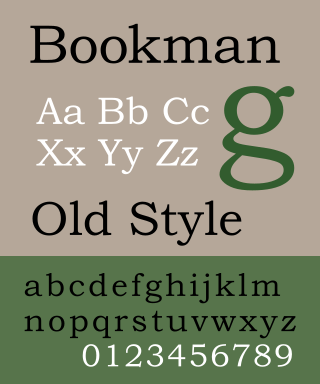

Bookman, or Bookman Old Style, is a serif typeface. A wide, legible design that is slightly bolder than most body text faces, Bookman has been used for both display typography, for trade printing such as advertising, and less commonly for body text. In advertising use it is particularly associated with the graphic design of the 1960s and 1970s, when revivals of it were very popular.

Joanna is a serif typeface designed by Eric Gill (1882–1940) from 1930 to 1931 that was named for one of his daughters. Gill chose Joanna for setting An Essay on Typography, a book by Gill on his thoughts on typography, typesetting and page design. He described it as "a book face free from all fancy business".

Robert Granjon was a French punchcutter, a designer and creator of metal type, and printer. He worked in Paris, Lyon, Antwerp, and Rome. He is best known for having introduced the typeface style Civilité, for his many italic types and his fleuron designs, although he worked across all genres of typeface and alphabet across his long career.

Les Grecs du roi are a celebrated and influential Greek alphabet typeface in the Greek minuscule style which was cut by the French punchcutter Claude Garamond between 1541 and 1550. Arthur Tilley calls the books printed from them "among the most finished specimens of typography that exist".

Imprint is a serif typeface created by Monotype, commonly used for body text. Originally called Imprint Old Face, it is a sturdy, amiable design with a large x-height, Caslon-like but with more regularity in its letterforms. It was commissioned by the London publishers of The Imprint, a short-lived printing trade periodical published during 1913.

ITC Galliard is the name of a serif typeface designed by Matthew Carter and issued in 1978 by the Mergenthaler Linotype Company.

A reverse-contrast or reverse-stress letterform is a design in which the stress is reversed from the norm: a typeface or custom lettering where the horizontal lines are the thickest. This is the reverse of the vertical lines being the same width or thicker than horizontals, which is normal in Latin-alphabet writing and especially printing. The result is a dramatic effect, in which the letters seem to have been printed the wrong way round. The style invented in the early nineteenth century as attention-grabbing novelty display designs. Modern font designer Peter Biľak, who has created a design in the genre, has described them as "a dirty trick to create freakish letterforms that stood out."

Solus is a serif typeface that was designed by English sculptor and stonemason Eric Gill for the British Monotype Corporation and released in 1929.

Christoffel van Dijck was a German-born Dutch punchcutter and typefounder, who cut punches and operated a foundry for casting metal type. Van Dijck's type was widely used at a time when Amsterdam had become a major centre of world printing.

Hendrik van den Keere was a punchcutter, or cutter of punches to make metal type, who lived in Ghent in modern Belgium.