Related Research Articles

Caligula, formally known as Gaius, was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 to 41. The son of the popular Roman general Germanicus and Augustus's granddaughter Agrippina the Elder, Caligula was born into the first ruling family of the Roman Empire, conventionally known as the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

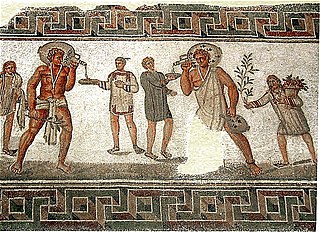

A gladiator was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gladiators were volunteers who risked their lives and their legal and social standing by appearing in the arena. Most were despised as slaves, schooled under harsh conditions, socially marginalized, and segregated even in death.

Ignatius of Antioch, also known as Ignatius Theophorus, was an early Christian writer and bishop of Antioch. While en route to Rome, where he met his martyrdom, Ignatius wrote a series of letters. This correspondence now forms a central part of a later collection of works known to be authored by the Apostolic Fathers. He is considered to be one of the three most important of these, together with Clement of Rome and Polycarp. His letters also serve as an example of early Christian theology. Important topics they address include ecclesiology, the sacraments, and the role of bishops.

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. The pillory is related to the stocks.

Quintus Aurelius Symmachus "Eusebius" was a Roman statesman, orator, and man of letters. He held the offices of governor of proconsular Africa in 373, urban prefect of Rome in 384 and 385, and consul in 391. Symmachus sought to preserve the traditional religions of Rome at a time when the aristocracy was converting to Christianity, and led an unsuccessful delegation of protest against Gratian, when he ordered the Altar of Victory removed from the curia, the principal meeting place of the Roman Senate in the Forum Romanum. Two years later he made a famous appeal to Gratian's successor, Valentinian II, in a dispatch that was rebutted by Ambrose, the bishop of Milan. Symmachus's career was temporarily derailed when he supported the short-lived usurper Magnus Maximus, but he was rehabilitated and three years later appointed consul. After the death of Theodosius I, he became an ally of Stilicho, the guardian of emperor Honorius. In collaboration with Stilicho he was able to restore some of the legislative powers of the Senate. Much of his writing has survived: nine books of letters; a collection of Relationes or official dispatches; and fragments of various orations.

The Third Servile War, also called by Plutarch the Gladiator War and the War of Spartacus, was the last in a series of slave rebellions against the Roman Republic, known as the Servile Wars. The Third was the only one directly to threaten the Roman heartland of Italy. It was particularly alarming to Rome because its military seemed powerless to suppress it.

Venatio was a type of entertainment in Roman amphitheaters involving the hunting and killing of wild animals.

A retiarius was a Roman gladiator who fought with equipment styled on that of a fisherman: a weighted net, a three-pointed trident, and a dagger (pugio). The retiarius was lightly armoured, wearing an arm guard (manica) and a shoulder guard (galerus). Typically, his clothing consisted only of a loincloth (subligaculum) held in place by a wide belt, or of a short tunic with light padding. He wore no head protection or footwear.

The gladiatrix is the female equivalent of the gladiator of ancient Rome. Like their male counterparts, female gladiators fought each other, or wild animals, to entertain audiences at various games and festivals. Very little is known about them. They were almost certainly considered an exotic rarity by their audiences. Their existence is known only through a few accounts written by members of Rome's elite, and a very small number of inscriptions.

The relationship between Christianity and politics is a historically complex subject and a frequent source of disagreement throughout the history of Christianity, as well as in modern politics between the Christian right and Christian left. There have been a wide variety of ways in which thinkers have conceived of the relationship between Christianity and politics, with many arguing that Christianity directly supports a particular political ideology or philosophy. Along these lines, various thinkers have argued for Christian communism, Christian socialism, Christian anarchism, Christian libertarianism, or Christian democracy. Others believe that Christians should have little interest or participation in politics or government.

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Besides manual labour, slaves performed many domestic services and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions. Accountants and physicians were often slaves. Slaves of Greek origin in particular might be highly educated. Unskilled slaves, or those sentenced to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills.

The inaugural games were held, on the orders of the Roman Emperor Titus, to celebrate the completion in AD 80 of the Colosseum, then known as the Flavian Amphitheatre. Vespasian began construction of the amphitheatre around AD 70 and it was completed by his son Titus who became emperor following Vespasian's death in AD 79. Titus' reign began with months of disasters – including the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, a fire in Rome, and an outbreak of plague – he inaugurated the completion of the structure with lavish games that lasted for more than one hundred days, perhaps in an attempt to appease the Roman public and the gods.

Quintus Sextius the Elder was a Roman philosopher, whose philosophy combined Pythagoreanism with Stoicism. His praises were frequently celebrated by Seneca.

Colosseum: Rome's Arena of Death aka Colosseum: A Gladiator's Story is a 2003 BBC Television and France 2 docudrama which tells the true story of Verus, a gladiator who fought at the Colosseum in Rome.

In the Roman Empire, the dediticii were one of the three classes of libertini. The dediticii existed as a class of persons who were neither slaves, nor Roman citizens (cives), nor Latini, at least as late as the time of Ulpian.

Damnatio ad bestias was a form of Roman capital punishment in which the condemned person was killed by wild animals, usually lions or other big cats. This form of execution, which first came to ancient Rome around the 2nd century BC, was part of the wider class of blood sports called Bestiarii.

An essedarius was a type of gladiator in Ancient Rome who fought from a chariot. The word had its origins for describing charioteers from Caesar's Gallic War, in his campaign against Britons in Britain. The gladiator type was inspired by these British fighters, although there are few references to essedarii in the literature. Petronius wrote about an essedarius fighting to the accompaniment of a water-organ. While Seneca speaks about a dismounted essedarius as a commentary on the inability to know a person in a different situation which implies they most likely fought from their chariots all the time. Suetonius mentions Caligula being so annoyed that he tripped leaving the amphitheater when an essedarius set free his enslaved driver received much applause. Caligula said "The people that rule the world give more honour to a gladiator for a trifling act than to their deified emperors or to the one still present with them".

Gladiator Begins is a fighting game developed by Japanese studio GOSHOW and published in Japan by Acquire on January 14, 2010, and in North America by Aksys Games on September 15, 2010. It is the prequel to the 2005 video game Colosseum: Road to Freedom, which was originally released for the PlayStation 2.

The Battle of Vesuvius was the first conflict of the Third Servile War which pitted the escaped slaves against a military force of militia specifically dispatched by Rome to deal with the rebellion.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Entry on Bestiarii at Chambers, Ephraim, Cyclopaedia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences , c. 1680-1740

- ↑ William Smith, "Bestiarii" from A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray: London, 1875. Public domain.

- ↑ The Bestiarius and the Ludus Matutinus

- ↑ Seneca. Epistles. LXX.20.

- ↑ Seneca. Epistles. LXX.23.

- ↑ Symmachus. Letters. II.46.

- ↑ Cyclopaedia, apparently referring to some one of Vigenère's French translations of Latin works, such as his translation of Caesar's Commentaries .

- ↑ Tertullian's Apologeticus , chapter 35; cited in Smith 1875.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bestiarii . |

| Look up bestiarius in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |