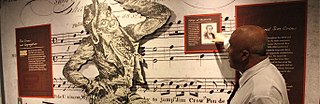

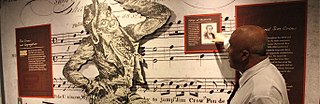

"Jump Jim Crow" or "Jim Crow" is a song and dance from 1828 that was done in blackface by white minstrel performer Thomas Dartmouth "Daddy" Rice. The song is speculated to have been taken from Jim Crow, a physically disabled enslaved African-American, who is variously claimed to have lived in St. Louis, Cincinnati, or Pittsburgh. The song became a 19th-century hit and Rice performed it all over the United States as "Daddy Pops Jim Crow".

The American alligator, sometimes referred to colloquially as a gator or common alligator, is a large crocodilian reptile native to the Southeastern United States. It is one of the two extant species in the genus Alligator, and is larger than the only other living alligator species, the Chinese alligator.

Pickaninny is a word applied originally by people of the West Indies to their babies and more widely referring to small children, as in Melanesian Pidgin. It is a pidgin word form, derived from the Portuguese pequenino.

The Black Codes, sometimes called Black Laws, were laws governing the conduct of African Americans. In 1832, James Kent wrote that "in most of the United States, there is a distinction in respect to political privileges, between free white persons and free colored persons of African blood; and in no part of the country do the latter, in point of fact, participate equally with the whites, in the exercise of civil and political rights." Although Black Codes existed before the Civil War and many Northern states had them, it was the Southern U.S. states that codified such laws in everyday practice. The best known of them were passed in 1865 and 1866 by Southern states, after the American Civil War, in order to restrict African Americans' freedom, and to compel them to work for low or no wages.

A mammy is a U.S. historical stereotype depicting black women who work in a white family and nurse the family's children. The fictionalized mammy character is often visualized as a larger-sized, dark-skinned woman with a motherly personality. The origin of the mammy figure stereotype is rooted in the history of slavery in the United States. Black slave women were tasked with domestic and childcare work in white American slaveholding households. The mammy stereotype was inspired by these domestic workers. The mammy caricature was used to create a narrative of black women being happy within slavery or within a role of servitude. The mammy stereotype associates black women with domestic roles and it has been argued it, combined with segregation and discrimination, limited job opportunities for black women during the Jim Crow era, approximately 1877 to 1966.

In the post-Reconstruction United States, Black Buck was a racial slur used to describe a certain type of African American man. In particular, the caricature was used to describe black men who absolutely refused to bend to the law of white authority and were seen as irredeemably violent, rude, and lecherous.

The tragic mulatto is a stereotypical fictional character that appeared in American literature during the 19th and 20th centuries, starting in 1837. The "tragic mulatto" is a stereotypical mixed-race person, who is assumed to be depressed, or even suicidal, because they fail to completely fit in the "white world" or the "black world". As such, the "tragic mulatto" is depicted as the victim of the society that is divided by race, where there is no place for one who is neither completely "black" nor "white".

Sewer alligator stories date back to the late 1920s and early 1930s; in most instances they are part of contemporary legend. They are based upon reports of alligator sightings in rather unorthodox locations, in particular New York City.

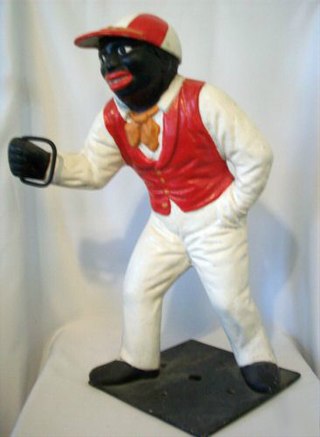

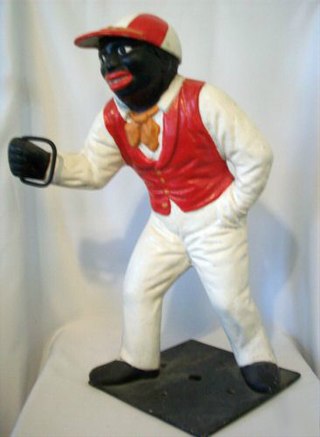

A lawn jockey is a statue depicting a man in jockey clothes, intended to be placed in front yards as hitching posts, similar to those of footmen bearing lanterns near entrances and gnomes in gardens. Because of the prevalence of black lawn jockeys with exaggerated features, the item is often regarded as being symbolic of the racism and racist imagery prevalent in the United States during the eras of slavery and Jim Crow laws. Today, lawn jockeys are often depicted as Caucasian boys to distance the artifact from racial connotations.

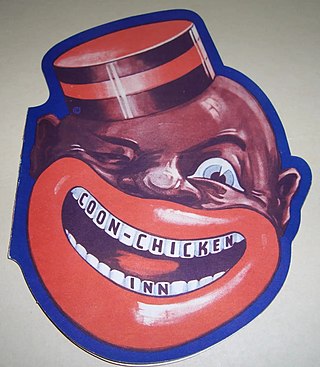

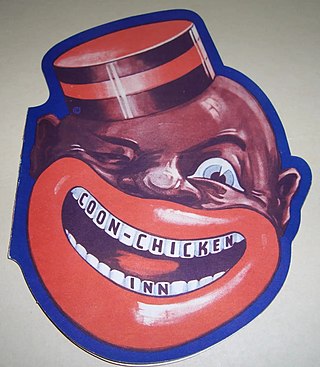

Coon Chicken Inn was an American chain of three restaurants that was founded by Maxon Lester Graham and Adelaide Burt in 1925, which prospered until the late 1950s. The restaurant's name contained the word Coon, considered a racial slur, and the trademarks and entrances of the restaurants were designed to look like a smiling caricature of an African-American porter. The smiling capped porter head also appeared on menus, dishes, and promotional items. Due to changes in popular culture and the general consideration of being culturally and racially offensive, the chain was closed by 1957.

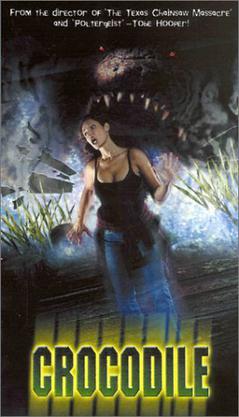

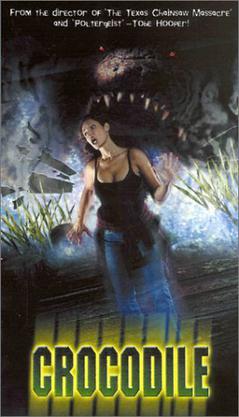

Crocodile is a 2000 American direct-to-video horror film directed by Tobe Hooper. The film involves a group of college students on a houseboat for spring break who stumble across a nest of eggs, and unknowingly enrage a large female Nile crocodile that stalks and kills them one by one. It was followed by Crocodile 2: Death Swamp, a film with no relation to the plot of the original beyond featuring a giant crocodile.

Stereotypes of African Americans are misleading beliefs about the culture of people of African descent who reside in the United States, largely connected to the racism and discrimination which African Americans are subjected to. These beliefs date back to the slavery of black people during the colonial era and they have evolved within American society.

The golliwog, also spelled golliwogg or shortened to golly, is a doll-like character – created by cartoonist and author Florence Kate Upton – that appeared in children's books in the late 19th century, usually depicted as a type of rag doll. It was reproduced, both by commercial and hobby toy-makers, as a children's toy called the "golliwog", a portmanteau of golly and polliwog, and had great popularity in the UK and Australia into the 1970s. The doll is characterised by jet black skin, eyes rimmed in white, exaggerated red lips and frizzy hair, a blackface minstrel tradition. Today the word is regarded as a racial slur towards black people.

African dodger, also known as Hit the Coon or Hit the Nigger Baby, was a carnival game played in the United States of America (USA). In the game, an African-American man would stick his head through a curtain, and attempt to dodge objects, such as eggs or baseballs, thrown at him by players. Despite the obvious brutality of hitting someone in the head with eggs or baseballs, it was a popular carnival game from the 1880s up to the 1960s. The victims often suffered serious injuries.

The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University, Big Rapids, Michigan, displays a wide variety of everyday artifacts depicting the history of racist portrayals of African Americans in American popular culture. The mission of the Jim Crow Museum is to use objects of intolerance to teach tolerance and promote social justice.

The angry black woman stereotype is a racial trope in American society and media that portrays Black American women as inherently ill-mannered and ill-tempered. Related concepts are the "Sapphire" or "Jezebel".

Anti-racism encompasses a range of ideas and political actions which are meant to counter racial prejudice, systemic racism, and the oppression of specific racial groups. Anti-racism is usually structured around conscious efforts and deliberate actions which are intended to provide equal opportunities for all people on both an individual and a systemic level. As a philosophy, it can be engaged in by the acknowledgment of personal privileges, confronting acts as well as systems of racial discrimination, and/or working to change personal racial biases. Major contemporary anti-racism efforts include Black Lives Matter organizing and workplace antiracism.

The Jolly Darkie Target Game was a game developed and manufactured by the McLoughlin Brothers which was released in 1890. It was produced until at least 1915. Other companies produced similar games, such as Alabama Coon by J. W. Spear & Sons.

The Brownies' Book was the first magazine published for African-American children and youth. Its creation was mentioned in the yearly children's issue of The Crisis in October 1919. The first issue was published during the Harlem Renaissance in January 1920, with issues published monthly until December 1921. It is cited as an "important moment in literary history" for establishing black children's literature in the United States.