Plot

The film is set during the 10th anniversary of a peaceful socialist-democratic revolution, and follows two feminist groups in New York City, each voicing their concerns to the public by pirate radio. One group, led by an outspoken white lesbian, Isabel, operates Radio Ragazza. The other, led by a soft-spoken African-American, Honey, operates Phoenix Radio. The local community is stimulated into action after a world-traveling political activist, Adelaide Norris, is arrested upon arriving at a New York City airport, and suspiciously dies while in police custody. Simultaneously, a Women's Army led by Hilary Hurst and advised by Zella, an elderly theorist and mentor, is taking direct action in the city. Initially, both Honey and Isabel refuse to join. This group, along with Norris and the radio stations, are under investigation by FBI agents. Their progress is tracked by three editors for a socialist newspaper, whose persistent and opinionated journalism ultimately gets them fired.

The story involves several different women with different perspectives and attempts to show several examples of how sexism plays out on the streets and how it can be combatted. In one scene, two men attack a woman on the sidewalk, forcing her to the ground. Before they can cause further harm, dozens of women on bicycles and blowing whistles come to chase the men away and help the woman. The movie shows women – despite their various differences – organizing in meetings, making radio shows, creating art, postering, working various jobs, etc. The film portrays a world rife with violence against women, high female unemployment, and government oppression. The women in the film start to come together to make a bigger impact, by means that some in their society consider terrorism.

Ultimately, after both radio stations are suspiciously burned down, Honey and Isabel team up and broadcast Phoenix Ragazza Radio from stolen vans. They also join the Women's Army, which sends a group of terrorists to interrupt a broadcast of the President of the United States, who is proposing that women be paid to do housework. The film ends with the women taking one more action, to bomb the antenna on top of the World Trade Center to hinder further destructive messages coming from the government and mainstream media.

Reception and legacy

Critical response

Rotten Tomatoes reports an 88% approval rating for the film based on 32 reviews, with an average rating of 6.8/10. [6]

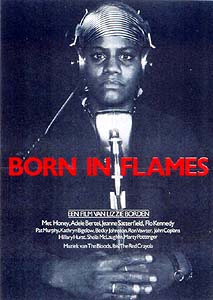

Variety said at the time of the film's release that it has "all the advantages and the disadvantages of a home movie", [7] while The Guardian in 2021 described the film as a zero-budget underground film with all the hallmarks of guerilla filmmaking, writing that "Borden is filming on the real New York streets, also using real news footage of real demos and real police violence" and that the "anarchic spirit of agitprop pulses from this scrappy, smart, subversive film." (In an interview, Borden herself said, "I could only shoot once a month, when I had $200 ... I would gather everyone in this old Lincoln Continental I kept parked in front of my loft, go somewhere and shoot, and then I'd spend the interim just editing.")

Janet Maslin of The New York Times wrote in 1983: "Only those who already share Miss Borden's ideas are apt to find her film persuasive." [2] Marjorie Baumgarten's 2001 review for The Austin Chronicle praised the film, saying: "Beautifully made, courageously edited, and swift-moving, this challenging, provocative film is a work that is both humanist and revolutionary." [8] Frances Dickinson of Time Out London wrote that Borden "[handles] her story with audacity and make[s] even the driest argument crackle with humour, while the more poignant moments burn with a fierce white heat." [9] TV Guide rated it 2/4 stars, saying: "This feminist film wins laurels for close attention to detail in a radical filmmaking effort." [10] Greg Baise of the Metro Times called it "an early '80s landmark of indie and queer cinema". [11] In 2022, the film was ranked joint 243rd in the Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time poll, tied for that ranking with 21 other films, including A Clockwork Orange , Annie Hall and Possession. [12]

References

- The movie refers to many feminist movements and tools, including black feminism, white feminism, consciousness raising, independent radio, and responses to police brutality.

- There is also a reference to wages for housework, a '70s feminist social movement addressing women's reproductive labor, in a scene in which the President announces on television: “For the first time in our history we’ll provide women with wages for housework,” just before a group of women hijack the broadcast to air a militant message. This moment in the film highlights political antagonisms between white heteronormative feminism and anti-racist / anti-capitalist feminism. [15]

- The movie also refers to U.S. policies like the Workfare program and the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of 1976, which in the film are taken to discriminate against single and queer women (in one scene, a TV news journalist announces that "male heads of families" would get jobs). [15]

- In his 2013 critical analysis, media historian Lucas Hilderbrand notes the film's parallels with the Combahee River Collective's A Black Feminist Statement (1977) [see 'Influence' below]. [16]

Influence

The film is discussed in Christina Lane's book Feminist Hollywood: From "Born in Flames" to "Point Break". [18]

A “graphic translation” of the movie made by artist Kaisa Lassinaro, which contains an interview of Lizzie Borden, was published by Occasional Papers in 2011. [19] The book is a collage composition made of screencaps with a selection of dialogues from the movie.

In 2013, a dossier on the film was published as a special issue of Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory. [20] With an introduction from Craig Willse and Dean Spade, the dossier includes a number of essays that address race, queerness, intersectionality, radicalism, violence, and feminism in the film.

The film has experienced something of a renaissance after the 35mm restoration print premiered in 2016 at the Anthology Film Archives. [21] followed by promotion by the Criterion Channel and a re-release that took Borden to screenings around the world. [22] Richard Brody of The New Yorker wrote "the free, ardent, spontaneous creativity of Born in Flames emerges as an indispensable mode of radical change—one that many contemporary filmmakers with political intentions have yet to assimilate." [23] He also wrote "Borden's exhilarating collage-like story stages news reports, documentary sequences, and surveillance footage alongside tough action scenes and musical numbers; her violent vision is both ideologically complex and chilling." [23] Melissa Anderson of The Village Voice wrote "this unruly, unclassifiable film — perhaps the sole entry in the hybrid genre of radical-lesbian-feminist sci-fi vérité — premiered two years into the Reagan regime, but its fury proves as bracing today as it was back when this country began its inexorable shift to the right." [24] Borden was invited to show the new 35mm print in Brussels, Barcelona, Madrid, San Sebastián, Milan, Toronto, the Edinburgh Film Festival, London Film Festival, along with screenings in Detroit, Rochester, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. [21]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.