This article needs additional citations for verification .(December 2017) |

Cannabis in Zimbabwe is a traditional crop, generally called mbanje, that is considered illegal except for licensed medical use. [1]

This article needs additional citations for verification .(December 2017) |

Cannabis in Zimbabwe is a traditional crop, generally called mbanje, that is considered illegal except for licensed medical use. [1]

Arrived centuries ago, Cannabis has a long history in Zimbabwe, with the first archaeological evidence estimated around 1200 CE and numerous evidence of use during the times of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe and later Kingdom of Mutapa. [2]

| | This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (August 2024) |

The plant is generally called mbanje, although other names are used such as suruma (near the Mozambique border). [2]

In the northwest Binga region, in particular, cannabis consumption "holds cultural significance as a social activity and where there are [traditional] medicinal uses for cannabis." [3]

Cannabis is illegal in Zimbabwe except for licensed medical use, and possession may be punished with up to 12 years in jail. [1]

On Friday 27 April 2018 Zimbabwe became the second African country to legalize marijuana for medical and scientific purposes. [4] [5] A press release published in Business Report on 30 April 2017 described how Zimbabweans were now allowed to “apply for licenses in growing cannabis specifically for medical and research.”[ citation needed ]

The country's health minister, David Parirenyatwa released the new policies for licensing of individuals and enterprises to cultivate Mbanje. The duration of licenses is a maximum of five years and renewable allowing growers to own, sell, and transport cannabis in dried and oil forms. Applicants are required to state plans for the growing site along with quantity for production and selling as well as production period. The health minister has the prerogative not to approve a license if it causes risks in terms of public health and security. [6]

The Zimbabwe Mail reported that ministers of parliament lobbied for the reduction of the “$50,000 license fee imposed on growers if they want to produce cannabis commercially.” According to these legislators, the fees are exorbitant and "will lock out poor farmers in farms like [those in the] Binga District who have been growing marijuana illegally". [7]

In 2017, Macro-Economic Planning and Investment Promotion Minister Dr Obert Mpofu noted that a Canadian firm had applied to cultivate medical cannabis in Zimbabwe, stating the government was "seriously considering" the application.

Reportedly, farmers were offered 100% ownership of their land for the cultivation of medicinal marijuana in May 2020. [8]

The new legislation has been criticised for not being

primarily aimed at providing alternative livelihoods for illicit producers, but rather at attracting foreign and local investment and promoting the legal industry as a key economic sector. Many people, including illicit cultivators, are unable to participate in the legal market due to barriers such as high license fees. […] License holders struggle to produce due to high production costs, regulatory and market hurdles, and the political and economic complexities. [3]

Observers have regretted "the risk of corporate capture" and undermining of "agribusiness’ production" associated with the reform. [9]

The Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 is a New Zealand drug control law that classifies drugs into three classes, or schedules, purportedly based on their projected risk of serious harm. However, in reality, classification of drugs outside of passing laws, where the restriction has no legal power, is performed by the governor-general in conjunction with the Minister of Health, neither of whom is actually bound by law to obey this restriction.

Drug liberalization is a drug policy process of decriminalizing, legalizing, or repealing laws that prohibit the production, possession, sale, or use of prohibited drugs. Variations of drug liberalization include drug legalization, drug relegalization, and drug decriminalization. Proponents of drug liberalization may favor a regulatory regime for the production, marketing, and distribution of some or all currently illegal drugs in a manner analogous to that for alcohol, caffeine and tobacco.

The use of cannabis in New Zealand is regulated by the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975, which makes unauthorised possession of any amount of cannabis a crime. Cannabis is the fourth-most widely used recreational drug in New Zealand, after caffeine, alcohol and tobacco, and the most widely used illicit drug. In 2001 a household survey revealed that 13.4% of New Zealanders aged 15–64 used cannabis. This ranked as the ninth-highest cannabis consumption level in the world.

Cannabis in the United Kingdom is illegal for recreational use and is classified as a Class B drug. In 2004, the United Kingdom made cannabis a Class C drug with less severe penalties, but it was moved back to Class B in 2009. Medical use of cannabis, when prescribed by a registered specialist doctor, was legalised in November 2018.

Cannabis is a plant used in Australia for recreational, medicinal and industrial purposes. In 2022–23, 41% of Australians over the age of fourteen years had used cannabis in their lifetime and 11.5% had used cannabis in the last 12 months.

Malawian cannabis, particularly the strain known as Malawi Gold, is internationally renowned as one of the finest sativa strains from Africa. According to a World Bank report it is among "the best and finest" marijuana strains in the world, generally regarded as one of the most potent psychoactive pure African sativas. The popularity of this variety has led to such a profound increase in marijuana tourism and economic profit in Malawi that Malawi Gold is listed as one of the three "Big C's" in Malawian exports: chambo, chombe (tea), and chamba (cannabis).

Cannabis is legal in Uruguay, and is one of the most widely used drugs in the nation.

Cannabis in India has been known to be used at least as early as 2000 BCE. In Indian society, common terms for cannabis preparations include charas (resin), ganja (flower), and bhang, with Indian drinks such as bhang lassi and bhang thandai made from bhang being one of the most common legal uses.

Cannabis had been illegal in Morocco since the nation's independence in 1956, reaffirmed by a total ban on drugs in 1974, but was partially tolerated in the country. Cannabis has been cultivated in Morocco for centuries and the country is currently among the world's top producers of hashish. As of 2024, Morocco was the world's top supplier of cannabis. On May 26, 2021, the Moroccan parliament voted to legalize the use of cannabis for medical, as well as cosmetic and industrial purposes.

Cannabis in South Africa is an indigenous plant with a rich historical, social, and cultural significance for various communities. South Africa’s cannabis policy evolution has been marked by significant shifts, particularly following decriminalisation by the Constitutional Court in 2018, and the passing of the Cannabis for Private Purposes Bill in May 2024.

Cannabis has been illegal in Nepal since 1976, but the country has a long history of use of cannabis for Ayurvedic medicine, intoxicant and as a holy offering for Hindu god Shiva and continues to produce cannabis illicitly.

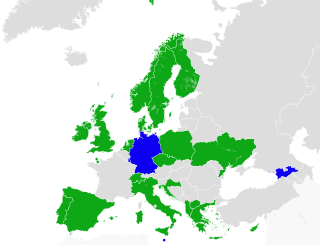

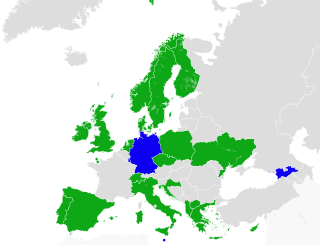

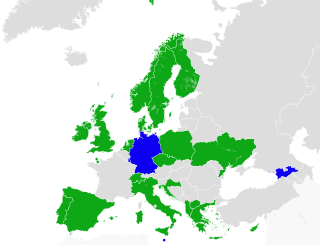

Cannabis in Germany has been legal for recreational usage by adults in a limited capacity since 1 April 2024, making it the ninth country in the world to legalise the drug. As of February 2024, it has been assessed that 4.5 million Germans use cannabis.

Cannabis is one of the most popular controlled substances for cultivation and consumption within the country of Belgium. Following global trends, cannabis consumption rates in Belgium have been steadily increasing across the country since the 20th century, and cannabis cultivation continues to expand rapidly on a national scale. Despite significant legal rework of cannabis-related laws since 2010, certain elements of the consumption and cultivation of cannabis are considered to exist within a “legal grey area” of Belgian law. Cannabis is technically illegal in Belgium, but personal possession has been decriminalised since 2003; adults over the age of 18 are allowed to possess up to 3 grams. The legal effort to restrict cultivation and growth has gradually subsided, resulting in an increase of the growth and consumption of cannabis and cannabis-related products.

Recreational cannabis is illegal for cultivation, trade and personal use in Lebanon. Nevertheless, large amounts of cannabis are grown illegally within the country, especially in the Bekka Valley, and consumed for personal use in private.

In Thailand, cannabis, known by the name Ganja has recently had new laws passed through. Cannabis that has less than 0.2% THC, referred to as industrial hemp in the USA, was legalised on 9 June 2022. Medicinal cannabis, with no THC restrictions, was made legal in 2018 but required patients to obtain a prescription from a medical practitioner. Recreational cannabis is still illegal according to Thai law.

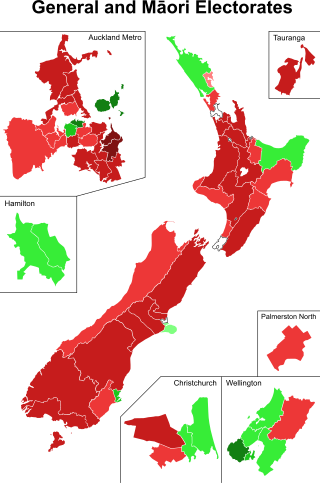

The 2020 New Zealand cannabis referendum was a non-binding referendum held on 17 October 2020 in conjunction with the 2020 general election and a euthanasia referendum, on the question of whether to legalise the sale, use, possession and production of recreational cannabis. It was rejected by New Zealand voters. The form of the referendum was a vote for or against the proposed "Cannabis Legalisation and Control Bill". Official results were released by the Electoral Commission on 6 November 2020 with 50.7% of voters opposing the legalisation and 48.4% in support.

Cannabis in Zambia is illegal for recreational use. In December 2019, by unanimous decision, it was legalized for export and medicinal purposes only. Cannabis is known as Zam-Blaze,"chamba", chwang, or dobo in Zambia.

Cannabis in Rwanda is legal for medicinal purposes, but illegal for recreational purposes.

Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development v Prince is a decision of the Constitutional Court of South Africa delivered on 18 September 2018, which found that it is unconstitutional for the state to criminalize the possession, use or cultivation of cannabis by adults for personal consumption in private.

Cannabis is illegal in Samoa.