Tumor-related

Tumors can cause pain by crushing or infiltrating tissue, or by releasing chemicals that make nociceptors responsive to stimuli that are normally non-painful (cf. allodynia).

Vascular events

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Between 15 and 25 percent of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is caused by cancer (often by a tumor compressing a vein). Cancers most likely to cause DVT are pancreatic cancer, stomach cancer, brain tumors, advanced breast cancer and advanced pelvic tumors. DVT may be the first hint that cancer is present. It causes swelling and pain (which varies from intense to vague cramp or "heaviness") in the legs, especially the calf, and (rarely) in the arms. [5]

- Superior vena cava syndrome

- The superior vena cava (a large vein carrying circulating, de-oxygenated blood into the heart) may be compressed by a tumor, most often non-small-cell lung carcinoma (50 percent), small-cell lung carcinoma (25 percent), lymphoma, or metastasis, causing superior vena cava syndrome. Common symptoms include shortness of breath, swelling of the face and neck, dilation of veins in the neck and chest, and chest wall pain. [5] [6]

Nervous system

Between 40 and 80 percent of patients with cancer pain experience neuropathic pain. [1]

Brain

- Brain tissue itself contains no nociceptors; brain tumors cause pain by pressing on blood vessels or the membrane that encapsulates the brain (the meninges), or indirectly by causing a build-up of fluid (edema) that may compress pain-sensitive tissue. [7]

Meninges

- Ten percent of patients with cancer spreading to different parts of the body develop meningeal carcinomatosis, where metastatic seedlings develop in the meninges (outer lining) of both the brain and spinal cord (with possible invasion of the brain or spinal cord). Melanoma and breast and lung cancer account for 90 percent of such cases. Back pain and headache – often severe and possibly associated with nausea, vomiting, neck rigidity and pain or discomfort in the eyes due to light exposure (photophobia) – are frequently the first symptoms of meningeal carcinomatosis. "Pins and needles" (paresthesia), bowel or bladder dysfunction and lower motor neuron weakness are common features. [8]

Spinal cord compression

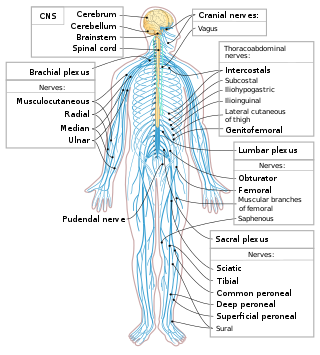

- About three percent of cancer patients experience spinal cord compression, usually from expansion of the vertebral body or pedicle (fig. 1) due to metastasis, sometimes involving collapse of the vertebral body. Occasionally compression is caused by nonvertebral metastasis adjacent to the spinal cord. Compression of the long tracts of the cord itself produces funicular pain and compression of a spinal nerve root (fig. 5) produces radicular pain. Seventy percent of cases involve the thoracic, 20 percent the lumbar, and 10 percent the cervical spine; and about 20 percent of cases involve multiple sites of compression. The nature of the pain depends on the location of the compression. [4]

Nerve infiltration or compression

- Infiltration or compression of a nerve by a primary tumor causes peripheral neuropathy in one to five percent of cancer patients. [4]

Dorsal root ganglion inflammation

- Small-cell lung cancer and, less often, cancer of the breast, colon or ovary may produce inflammation of the dorsal root ganglia (fig. 5), precipitating burning, tingling pain in the extremities, with occasional "lightning" or lancinating pains. [4] [9]

Brachial plexopathy

- Brachial plexopathy is a common product of Pancoast tumor, lymphoma and breast cancer, and can produce severe burning dysesthesic pain on the back of the hand, and cramping, crushing forearm pain. [4]

Bone

Invasion of bone by cancer is the most common source of cancer pain. About 70 percent of breast and prostate cancer patients, and 40 percent of those with lung, kidney and thyroid cancers develop bone metastases. It is commonly felt as tenderness, with constant background pain and instances of spontaneous or movement-related exacerbation, and is frequently described as severe. Tumors in the marrow instigate a vigorous immune response which enhances pain sensitivity, and they release chemicals that stimulate nociceptors. As they grow, tumors compress, consume, infiltrate or cut off blood supply to body tissues, which can cause pain. [4] [8]

Fracture

- Rib fractures, common in breast, prostate and other cancers with rib metastases, can cause brief severe pain on twisting the trunk, coughing, laughing, breathing deeply or moving between sitting and lying. [4] In breast, prostate or lung cancer, multiple myeloma and some other cancers, sudden onset limb or back pain may indicate pathological bone fracture (most often in the upper femur). [5]

Skull

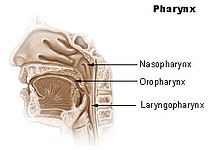

- The base of the skull may be affected by metastases from cancer of the bronchus, breast or prostate, or cancer may spread directly to this area from the nasopharynx (fig. 2), and this may cause headache, facial paresthesia, dysesthesia or pain, or cranial nerve dysfunction – the exact symptoms depend on the cranial nerves impacted. [4]

Pelvis

Pain produced by cancer within the pelvis varies depending on the affected tissue, but it frequently radiates diffusely to the upper thigh, and may refer to the lumbar region. Lumbosacral plexopathy is often caused by recurrence of cancer in the presacral space, and may refer to the external genitalia or perineum. Local recurrence of cancer attached to the side of the pelvic wall may cause pain in one of the iliac fossae. Pain on walking that confines the patient to bed indicates possible cancer adherence to or invasion of the iliacus muscle. Pain in the hypogastrium (between the navel and pubic bone) is often found in cancers of the uterus and bladder, and sometimes in colorectal cancer especially if infiltrating or attached to either uterus or bladder. [4]

Viscera

Visceral pain is diffuse and difficult to locate, and is often referred to more distant, usually superficial, sites. [8]

Liver

- Acute hemorrhage into a hepatocellular carcinoma causes severe upper right quadrant pain, and may be life-threatening, requiring emergency surgery or other emergency intervention. [5]

A tumor can expand the size of the liver several times and consequent stretching of its capsule can cause aching pain in the right hypochondrium. Other causes of pain in enlarged liver are traction of the supporting ligaments when standing or walking, the liver pressing against the rib cage or pinching the wall of the abdomen, and straining the lumbar spine. In some postures the liver may pinch the parietal peritoneum against the lower rib cage, producing sharp, transitory pain, relieved by changing position. The tumor may also infiltrate the liver's capsule, causing dull, and sometimes stabbing pain. [4]

Kidneys and spleen

- Cancer of the kidneys and spleen produces less pain than that caused by liver tumor – kidney tumors eliciting pain only once the organ has been almost totally destroyed and the cancer has invaded the surrounding tissue or adjacent pelvis. Pressure on the kidney or ureter from a tumor outside the kidney can cause extreme flank pain. [7] Local recurrence of cancer after the removal of a kidney can cause pain in the lumbar back, or L1 or L2 spinal nerve pain in the groin or upper thigh, accompanied by weakness and numbness of the iliopsoas muscle, exacerbated by activity. [4]

Abdominal and urogenital hollow organs

- Inflammation of artery walls and tissue adjacent to nerves is common in tumors of abdominal and urogenital hollow organs. [10] Infection or cancer may irritate the trigone of the urinary bladder, causing spasm of the detrusor urinae muscle (the muscle that squeezes urine from the urinary bladder), resulting in deep pain above the pubic bone, possibly referred to the tip of the penis, lasting from a few minutes to half an hour. [4]

Gastrointestinal

- The pain of intestinal tumors may be the result of disturbed motility, dilation, altered blood flow or ulceration. Malignant lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract can produce large tumors with significant ulceration and bleeding. [10]

Respiratory system

- Cancer in the bronchial tree is usually painless, [10] but ear and facial pain on one side of the head has been reported in some patients. This pain is referred via the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. [4]

Fig. 3 The pancreas: 1. pancreatic head; 4. pancreatic body; 11. pancreatic tail

Pancreas

- Ten percent of patients with cancer of the pancreatic body or tail experience pain, whereas 90 percent of those with cancer of the pancreatic head will, especially if the tumor is near the hepatopancreatic ampulla. The pain appears on the left or right upper abdomen, is constant, and increases in intensity over time. It is in some cases relieved by leaning forward and heightened by lying on the stomach. Back pain may be present and, if intense, may spread left and right. Back pain may be referred from the pancreas, or may indicate the cancer has penetrated paraspinal muscle, or entered the retroperitoneum and paraaortic lymph nodes [4]

Rectum

- A local tumor in the rectum or recurrence involving the presacral plexus may cause pain normally associated with an urgent need to defecate. This pain may, rarely, return as phantom pain after surgical removal of the rectum, though pain within a few weeks of surgical removal of the rectum is usually neuropathic pain due to the surgery (described in one study [11] as spontaneous, intermittent, mild to moderate shooting and bursting, or tight and aching), and pain emerging after three months (described as deep, sharp, aching, intense, and continuous, made worse by sitting or pressure) usually signals recurrence of the disease. The emergence of pain on standing or walking (described as "dragging") may indicate a deeper recurrence involving attachment to muscle or fascia. [4]

Serous mucosa

Carcinosis of the peritoneum may cause pain through inflammation, disordered visceral motility, or pressure of the metastases on nerves. Once a tumor has penetrated or perforated hollow viscera, acute inflammation of the peritoneum appears, inducing severe abdominal pain. Pleural carcinomatosis is normally painless. [10]

Soft tissue

Invasion of soft tissue by a tumor can cause pain by inflammatory or mechanical stimulation of nociceptors, or destruction of mobile structures such as ligaments, tendons and skeletal muscles. [10]