Native American gaming comprises casinos, bingo halls, slots halls and other gambling operations on Indian reservations or other tribal lands in the United States. Because these areas have tribal sovereignty, states have limited ability to forbid gambling there, as codified by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988. As of 2011, there were 460 gambling operations run by 240 tribes, with a total annual revenue of $27 billion.

The Pequot are a Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut including the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, or the Brothertown Indians of Wisconsin. They historically spoke Pequot, a dialect of the Mohegan-Pequot language, which became extinct by the early 20th century. Some tribal members are undertaking revival efforts.

The Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation is a federally recognized American Indian tribe in the state of Connecticut. They are descended from the Pequot people, an Algonquian-language tribe that dominated the southern New England coastal areas, and they own and operate Foxwoods Resort Casino within their reservation in Ledyard, Connecticut. As of 2018, Foxwoods Resort Casino is one of the largest casinos in the world in terms of square footage, casino floor size, and number of slot machines, and it was one of the most economically successful in the United States until 2007, but it became deeply in debt by 2012 due to its expansion and changing conditions.

Ledyard is a Town in New London County, Connecticut, United States, located along the Thames River. The town is named after Colonel William Ledyard, a Revolutionary War officer who was killed at the Battle of Groton Heights. The town is part of the Southeastern Connecticut Planning Region. The population was 15,413 at the 2020 census. The Foxwoods Resort Casino, owned and operated by the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, is located in the northeastern section of Ledyard, on the reservation owned by the tribe.

Foxwoods Resort Casino is a hotel and casino complex owned and operated by the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation on their reservation located in Ledyard, Connecticut. Including six casinos, the resort covers an area of 9,000,000 sq ft (840,000 m2). The casinos have more than 250 gaming tables for blackjack, craps, roulette, and poker, and have more than 5,500 slot machines. The casinos also have several restaurants, among them a Hard Rock Cafe. It has been developed since changes in state and federal laws in the late 20th century enabled Native American gaming on the sovereign reservations of federally recognized tribes.

The Golden Hill Paugussett is a state-recognized Native American tribe in Connecticut. Granted reservations in a number of towns in the 17th century, their land base was whittled away until they were forced to reacquire a small amount of territory in the 19th century. Today they retain a state-recognized reservation in the town of Trumbull, and have an additional reservation acquired in 1978 and 1980 in Colchester, Connecticut.

The Nonintercourse Act is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the United States Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set boundaries of American Indian reservations. The various acts were also intended to regulate commerce between White Americans and citizens of Indigenous nations. The most notable provisions of the act regulate the inalienability of aboriginal title in the United States, a continuing source of litigation for almost 200 years. The prohibition on purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government has its origins in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783.

The Schaghticoke are a Native American tribe of the Eastern Woodlands who historically consisted of Mahican, Potatuck, Weantinock, Tunxis, Podunk, and their descendants, peoples indigenous to what is now New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. The remnant tribes amalgamated in the area near the Connecticut-New York border after many losses, including the sale of some Schaghticoke and members of neighboring tribes into slavery in the Caribbean in the 1600s.

The Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation is an American Indian tribe in southeastern Connecticut descended from the Pequot people who dominated southeastern New England in the seventeenth century. It is one of five tribes recognized by the state of Connecticut.

The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act is a 1988 United States federal law that establishes the jurisdictional framework that governs Indian gaming. There was no federal gaming structure before this act. The stated purposes of the act include providing a legislative basis for the operation/regulation of Indian gaming, protecting gaming as a means of generating revenue for the tribes, encouraging economic development of these tribes, and protecting the enterprises from negative influences. The law established the National Indian Gaming Commission and gave it a regulatory mandate. The law also delegated new authority to the U.S. Department of the Interior and created new federal offenses, giving the U.S. Department of Justice authority to prosecute them.

The Mohegan are an Algonquian Native American tribe historically based in present-day Connecticut. Today the majority of the people are associated with the Mohegan Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe living on a reservation in the eastern upper Thames River valley of south-central Connecticut. It is one of two federally recognized tribes in the state, the other being the Mashantucket Pequot, whose reservation is in Ledyard, Connecticut. There are also three state-recognized tribes: the Schaghticoke, Paugusett, and Eastern Pequot.

Richard Arthur Hayward, also known as Skip Hayward, was the tribal chairman of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe from 1975 until November 1, 1998. He was replaced by Kenneth M. Reels. Before becoming the tribal chairman, he worked as a pipefitter at General Dynamics Electric Boat and lived in Stonington, Connecticut. In 1994, the University of Connecticut awarded him an honorary degree.

The Mashantucket Pequot Reservation Archeological District is a historic district in the northeast corner of the town of Ledyard, Connecticut. The district includes nearly 1,638 acres (6.63 km2) of archeologically sensitive land in the northern portion of the uplands historically called Wawarramoreke by the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe. It is within territory documented as Pequot land in the earliest-known surviving map (1614) of the region. The district was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986 and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1993.

Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton, 528 F.2d 370, was a landmark decision regarding aboriginal title in the United States. The United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit held that the Nonintercourse Act applied to the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot, non-federally-recognized Indian tribes, and established a trust relationship between those tribes and the federal government that the State of Maine could not terminate.

Indian Land Claims Settlements are settlements of Native American land claims by the United States Congress, codified in 25 U.S.C. ch. 19.

Thomas Norton Tureen is an American lawyer, investment banker and entrepreneur known for his work with American Indian tribes. While an attorney with the Native American Rights Fund he pioneered the use of the Nonintercourse Act to obtain return of tribal lands lost 180 years earlier and federal recognition for previously non-federally recognized tribes. Tureen successfully litigated Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton (1975), which established that the federal government has a trust responsibility to protect the land of all tribes, including those not previously recognized, and that all tribes are entitled to the benefits and immunities associated with federal recognition. Between 1972 and 1983 he was lead counsel in cases that obtained federal recognition for and achieved the return of over 300,000 acres to five New England tribes. He helped the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, now one of the most successful gaming operators in the U.S., obtain federal recognition in 1984 pursuant to regulations adopted by the Department of the Interior in response to the Passamaquoddy decision. His work on behalf of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe in Connecticut led to the creation of the Foxwoods Resort Casino, which was the largest casino in the world when opened. And he arranged the acquisition of Dragon Cement, New England's only cement producer, by the Passamaquoddy Tribe, and Phoenix Cement by the Salt River Pima Maricopa Indian Community, ; originated 250 MW Moapa Solar, the first utility scale solar project in Indian Country, and originated a partnership controlled by the Morongo Band of Mission Indians that became the first tribal participating transmission owner in the U.S. and the Native American Finance Officers Association (NAFOA) 2023 Impact Deal of the Year.

The Narragansett Trail is a 16 miles (26 km) hiking trail located in Connecticut. It is one of the Blue-Blazed Trails maintained by the Connecticut Forest and Park Association, the Narragansett Council, and the Rhode Island chapter of Scouts BSA.

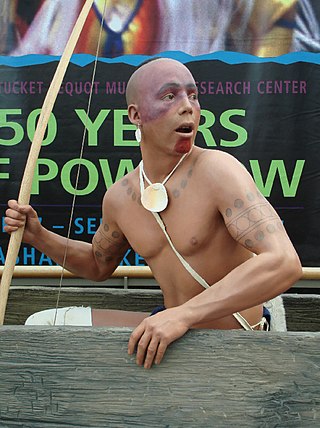

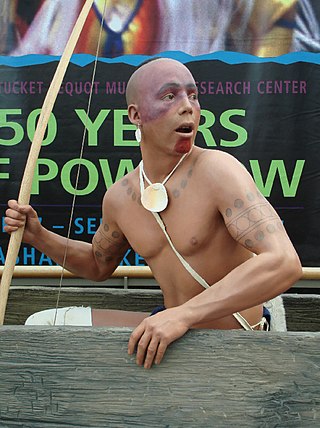

The Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center is a museum of Native American culture in Mashantucket, Connecticut, owned and operated by the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation.

Legal forms of gambling in the U.S. state of Connecticut include two Indian casinos, parimutuel wagering, charitable gaming, the Connecticut Lottery, and sports betting.

Robin Cassacinamon (c.1620s-1692) was a Pequot Indian governor appointed by the United Colonies to govern Pequots in southeastern Connecticut.