In economics and finance, arbitrage is the practice of taking advantage of a difference in prices in two or more markets – striking a combination of matching deals to capitalize on the difference, the profit being the difference between the market prices at which the unit is traded. When used by academics, an arbitrage is a transaction that involves no negative cash flow at any probabilistic or temporal state and a positive cash flow in at least one state; in simple terms, it is the possibility of a risk-free profit after transaction costs. For example, an arbitrage opportunity is present when there is the possibility to instantaneously buy something for a low price and sell it for a higher price.

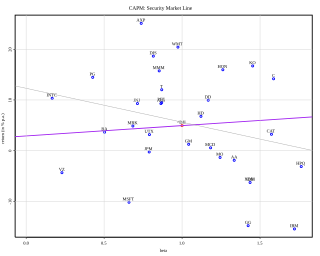

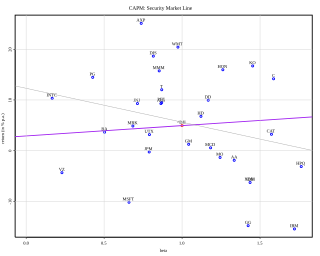

In finance, the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) is a model used to determine a theoretically appropriate required rate of return of an asset, to make decisions about adding assets to a well-diversified portfolio.

In financial mathematics, the put–call parity defines a relationship between the price of a European call option and European put option, both with the identical strike price and expiry, namely that a portfolio of a long call option and a short put option is equivalent to a single forward contract at this strike price and expiry. This is because if the price at expiry is above the strike price, the call will be exercised, while if it is below, the put will be exercised, and thus in either case one unit of the asset will be purchased for the strike price, exactly as in a forward contract.

A risk premium is a measure of excess return that is required by an individual to compensate being subjected to an increased level of risk. It is used widely in finance and economics, the general definition being the expected risky return less the risk-free return, as demonstrated by the formula below.

Rational pricing is the assumption in financial economics that asset prices – and hence asset pricing models – will reflect the arbitrage-free price of the asset as any deviation from this price will be "arbitraged away". This assumption is useful in pricing fixed income securities, particularly bonds, and is fundamental to the pricing of derivative instruments.

Modern portfolio theory (MPT), or mean-variance analysis, is a mathematical framework for assembling a portfolio of assets such that the expected return is maximized for a given level of risk. It is a formalization and extension of diversification in investing, the idea that owning different kinds of financial assets is less risky than owning only one type. Its key insight is that an asset's risk and return should not be assessed by itself, but by how it contributes to a portfolio's overall risk and return. The variance of return is used as a measure of risk, because it is tractable when assets are combined into portfolios. Often, the historical variance and covariance of returns is used as a proxy for the forward-looking versions of these quantities, but other, more sophisticated methods are available.

In finance, the beta is a statistic that measures the expected increase or decrease of an individual stock price in proportion to movements of the stock market as a whole. Beta can be used to indicate the contribution of an individual asset to the market risk of a portfolio when it is added in small quantity. It refers to an asset's non-diversifiable risk, systematic risk, or market risk. Beta is not a measure of idiosyncratic risk.

Floating rate notes (FRNs) are bonds that have a variable coupon, equal to a money market reference rate, like SOFR or federal funds rate, plus a quoted spread. The spread is a rate that remains constant. Almost all FRNs have quarterly coupons, i.e. they pay out interest every three months. At the beginning of each coupon period, the coupon is calculated by taking the fixing of the reference rate for that day and adding the spread. A typical coupon would look like 3 months USD SOFR +0.20%.

In finance, Jensen's alpha is used to determine the abnormal return of a security or portfolio of securities over the theoretical expected return. It is a version of the standard alpha based on a theoretical performance instead of a market index.

In finance, interest rate immunization is a portfolio management strategy designed to take advantage of the offsetting effects of interest rate risk and reinvestment risk.

In finance, leverage, also known as gearing, is any technique involving borrowing funds to buy an investment.

Alpha is a measure of the active return on an investment, the performance of that investment compared with a suitable market index. An alpha of 1% means the investment's return on investment over a selected period of time was 1% better than the market during that same period; a negative alpha means the investment underperformed the market.

In finance and investing, rebalancing of investments is a strategy of bringing a portfolio that has deviated away from one's target asset allocation back into line. This can be implemented by transferring assets, that is, selling investments of an asset class that is overweight and using the money to buy investments in a class that is underweight, but it also applies to adding or removing money from a portfolio, that is, putting new money into an underweight class, or making withdrawals from an overweight class.

Dynamic asset allocation is a strategy used by investment products such as hedge funds, mutual funds, credit derivatives, index funds, principal protected notes and other structured investment products to achieve exposure to various investment opportunities and provide 100% principal protection.

In finance, diversification is the process of allocating capital in a way that reduces the exposure to any one particular asset or risk. A common path towards diversification is to reduce risk or volatility by investing in a variety of assets. If asset prices do not change in perfect synchrony, a diversified portfolio will have less variance than the weighted average variance of its constituent assets, and often less volatility than the least volatile of its constituents.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to finance:

A fund derivative is a financial structured product related to a fund, normally using the underlying fund to determine the payoff. This may be a private equity fund, mutual fund or hedge fund. Purchasers obtain exposure to the underlying fund whilst improving their risk profile over a direct investment.

On March 23, 2009, the United States Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Federal Reserve, and the United States Treasury Department announced the Public–Private Investment Program for Legacy Assets. The program is designed to provide liquidity for so-called "toxic assets" on the balance sheets of financial institutions. This program is one of the initiatives coming out of the implementation of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) as implemented by the U.S. Treasury under Secretary Timothy Geithner. The major stock market indexes in the United States rallied on the day of the announcement rising by over six percent with the shares of bank stocks leading the way. As of early June 2009, the program had not been implemented yet and was considered delayed. Yet, the Legacy Securities Program implemented by the Federal Reserve has begun by fall 2009 and the Legacy Loans Program is being tested by the FDIC. The proposed size of the program has been drastically reduced relative to its proposed size when it was rolled out.

Risk parity is an approach to investment management which focuses on allocation of risk, usually defined as volatility, rather than allocation of capital. The risk parity approach asserts that when asset allocations are adjusted to the same risk level, the risk parity portfolio can achieve a higher Sharpe ratio and can be more resistant to market downturns than the traditional portfolio. Risk parity is vulnerable to significant shifts in correlation regimes, such as observed in Q1 2020, which led to the significant underperformance of risk-parity funds in the Covid-19 sell-off.

A with-profits policy (Commonwealth) or participating policy (U.S.) is an insurance contract that participates in the profits of a life insurance company. The company is often a mutual life insurance company, or had been one when it began its with-profits product line. Similar arrangements are found in other countries such as those in continental Europe.