The Louisiana Purchase was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River's drainage basin west of the river. In return for fifteen million dollars, or approximately eighteen dollars per square mile, the United States nominally acquired a total of 828,000 sq mi in Middle America. However, France only controlled a small fraction of this area, most of which was inhabited by Native Americans; effectively, for the majority of the area, the United States bought the preemptive right to obtain Indian lands by treaty or by conquest, to the exclusion of other colonial powers.

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war fought between 1798 to 1800 by the United States and the French First Republic. It took place at sea, primarily the Caribbean and the East Coast of the United States.

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, 1st Prince of Benevento, then Prince of Talleyrand, was a French secularized clergyman, statesman, and leading diplomat. After studying theology, he became Agent-General of the Clergy in 1780. In 1789, just before the French Revolution, he became Bishop of Autun. He worked at the highest levels of successive French governments, most commonly as foreign minister or in some other diplomatic capacity. His career spanned the regimes of Louis XVI, the years of the French Revolution, Napoleon, Louis XVIII, and Louis Philippe I. Those Talleyrand served often distrusted him but, like Napoleon, found him extremely useful. The name "Talleyrand" has become a byword for crafty and cynical diplomacy.

The Treaty of Amiens temporarily ended hostilities between France, the Spanish Empire, and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it set the stage for the Napoleonic Wars. Britain gave up most of its recent conquests; France was to evacuate Naples and Egypt. Britain retained Ceylon and Trinidad.

The Treaty of Lunéville was signed in the Treaty House of Lunéville on 9 February 1801. The signatory parties were the French Republic and Emperor Francis II, who signed on his own behalf as ruler of the hereditary domains of the House of Austria and on behalf of the Holy Roman Empire. The signatories were Joseph Bonaparte and Count Ludwig von Cobenzl, the Austrian foreign minister. The treaty formally ended Austrian and Imperial participation in the War of the Second Coalition and the French Revolutionary Wars, as well as the Imperial Kingdom of Italy.

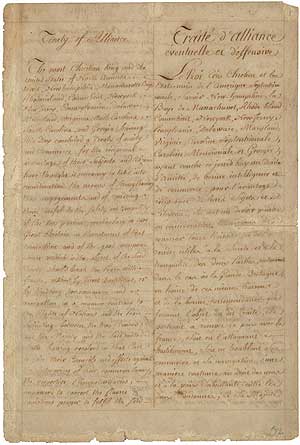

The Treaty of Alliance, also known as the Franco-American Treaty, was a defensive alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States formed amid the American Revolutionary War with Great Britain. It was signed by delegates of King Louis XVI and the Second Continental Congress in Paris on February 6, 1778, along with the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and a secret clause providing for the entry of other European allies; together these instruments are sometimes known as the Franco-American Alliance or the Treaties of Alliance. The agreements marked the official entry of the United States on the world stage, and formalized French recognition and support of U.S. independence that was to be decisive in America's victory.

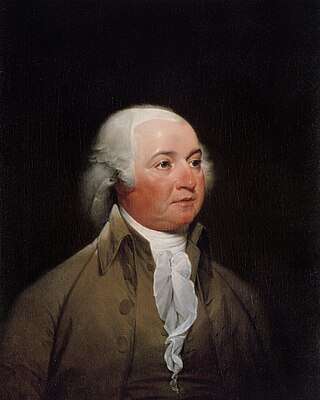

The XYZ Affair was a political and diplomatic episode in 1797 and 1798, early in the presidency of John Adams, involving a confrontation between the United States and Republican France that led to the Quasi-War. The name derives from the substitution of the letters X, Y, and Z for the names of French diplomats Jean-Conrad Hottinguer (X), Pierre Bellamy (Y), and Lucien Hauteval (Z) in documents released by the Adams administration.

The War of the Second Coalition was the second war targeting revolutionary France by many European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria, and Russia and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, Naples and various German monarchies. Prussia did not join the coalition, while Spain supported France.

The history of the United States from 1789 to 1815 was marked by the nascent years of the American Republic under the new U.S. Constitution.

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso was a secret agreement signed on 1 October 1800 between Spain and the French Republic by which Spain agreed in principle to exchange its North American colony of Louisiana for territories in Tuscany. The terms were later confirmed by the March 1801 Treaty of Aranjuez.

The West Florida Controversy included two border disputes that involved Spain and the United States in relation to the region known as West Florida over a period of 37 years. The first dispute commenced immediately after Spain received the colonies of West and East Florida from the Kingdom of Great Britain following the American Revolutionary War. Initial disagreements were settled with Pinckney's Treaty of 1795.

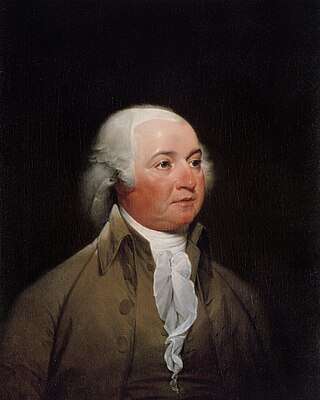

The presidency of John Adams, began on March 4, 1797, when John Adams was inaugurated as the second president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1801. Adams, who had served as vice president under George Washington, took office as president after winning the 1796 presidential election. The only member of the Federalist Party to ever serve as president, his presidency ended after a single term following his defeat in the 1800 presidential election. He was succeeded by Thomas Jefferson of the opposition Democratic-Republican Party.

The Treaty of Aranjuez (1801) was signed on 21 March 1801 between France and Spain. It confirmed a previous secret agreement in which Spain agreed to exchange Louisiana for territories in Tuscany. The treaty also stipulated Spain's cession of Louisiana to be a "restoration", not a retrocession.

The Treaty of Badajoz is a peace treaty of the XIX-th century signed by Spain and Portugal on 6 June 1801. Portugal ceded the border town of Olivenza to Spain and closed its ports to British military and commercial shipping.

Diplomacy was a central component of the American Revolutionary War and broader American Revolution. In the years leading up to the outbreak of military hostilities in 1775, the Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain had sought a peaceful diplomatic solution within the British political system. Once fighting began, diplomacy in the American Revolutionary War became critical to each faction for both strategic and ideological reasons. The American colonists sought forward aid and support to counter Great Britain's overwhelming strategic, military, and manpower advantages as well as to garner political legitimacy through international recognition; Great Britain sought to contain these diplomatic overtures while also leveraging its foreign relations with Native American tribes and German states. The American Declaration of Independence in July 1776 escalated these developments as the erstwhile sovereign United States evolved an independent foreign policy. Diplomacy would prove critical to shaping the trajectory and outcome of the war, as Americans relations with several foreign powers—particularly France and Spain—allowed access to decisive war material, funds, and troops while at the same time isolating Britain globally and spreading thin its military.

The Franco-American alliance was the 1778 alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States during the American Revolutionary War. Formalized in the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, it was a military pact in which the French provided many supplies for the Americans. The Netherlands and Spain later joined as allies of France; Britain had no European allies. The French alliance was possible once the Americans captured a British invasion army at Saratoga in October 1777, demonstrating the viability of the American cause. The alliance became controversial after 1793 when Great Britain and Revolutionary France again went to war and the U.S. declared itself neutral. Relations between France and the United States worsened as the latter became closer to Britain in the Jay Treaty of 1795, leading to an undeclared Quasi War. The alliance was defunct by 1794 and formally ended in 1800.

Joseph R. E. Bunel was a representative of the Haitian Revolutionary Government, who negotiated the first trade agreement between his nation and the United States, in 1799.

John Adams (1735–1826) was an American Founding Father who served as one of the most important diplomats on behalf of the new United States during the American Revolution. He served as minister to the Kingdom of France and the Dutch Republic and then helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris to end the American Revolutionary War.

The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1776 to 1801 concerns the foreign policy of the United States during the twenty five years after the United States Declaration of Independence (1776). For the first half of this period, the U.S. f8, U.S. foreign policy was conducted by the presidential administrations of George Washington and John Adams. The inauguration of Thomas Jefferson in 1801 marked the start of the next era of U.S. foreign policy.