The Bakweri are a Bantu ethnic group of the Republic of Cameroon. They are closely related to Cameroon's coastal peoples, particularly the Duala and Isubu.

The Duala are a Bantu ethnic group of Cameroon. They primarily inhabit the littoral and southwest region of Cameroon and form a portion of the Sawabantu or "coastal people" of Cameroon. The Dualas readily welcomed German and French colonial policies. The number of German-speaking Africans increased in central African German colonies prior to 1914. The Duala leadership in 1884 placed the tribe under German rule. Most converted to Protestantism and were schooled along German lines. Colonial officials and businessmen preferred them as inexpensive clerks to German government offices and firms in Africa. They have historically played a highly influential role in Cameroon due to their long contact with Europeans, high rate of education, and wealth gained over centuries as slave traders and landowners.

The Mungo (Moungo) are an ethnic group of the Republic of Cameroon. Along with the other coastal peoples, they belong to the Sawa ethnic groups. The Mungo have historically been dominated by the Duala people, and the two groups share similar cultures, histories, and claims of origin.

The Subu are a Bantu ethnic group who inhabit part of the coast of Cameroon. Along with other coastal peoples, they belong to Cameroon's Sawa ethnic groups. They were one of the earliest Cameroonian peoples to make contact with Europeans, and over two centuries, they became influential traders and middlemen. Under the kings William I of Bimbia and Young King William, the Isubu formed a state called Bimbia.

A jengu is a water spirit in the traditional beliefs of the Sawabantu groups of Cameroon, like the Duala, Bakweri, Malimba, Subu, Bakoko, Oroko people. Among the Bakweri, the term used is liengu. Miengu are similar to bisimbi in the Bakongo spirituality and Mami Wata. The Bakoko people use the term Bisima.

The Bakole are a Bantu ethnic group of the Republic of Cameroon. They belong to the Sawa, or Cameroonian coastal peoples. The Bakole speak a language of the same name.

The Mulimba are an ethnic group of the Republic of Cameroon. They belong to the Sawa peoples, those of the Cameroonian coast.

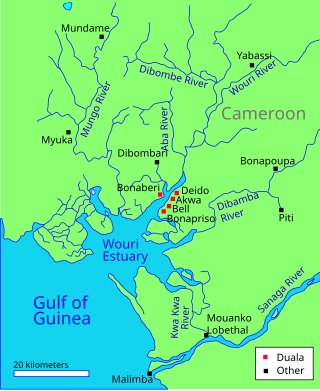

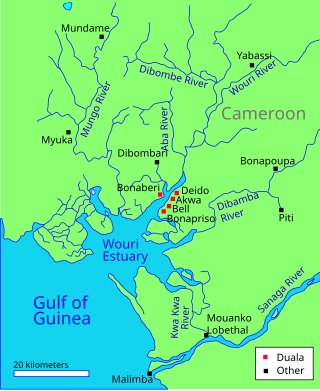

Mbedi a Mbongo is the common ancestor of many of the Sawa coastal ethnic groups of Cameroon according to their oral traditions. Stories say that he lived at a place called Piti, northeast of present-day Douala. From there, his sons migrated south toward the coast in what are known as the Mbedine events. These movements may be mythical in many cases, but anthropologists and historians accept the plausibility of a migration of some Sawa ancestors to the coast during the 16th century.

Mbongo is the common ancestor of the Sawa peoples of Cameroon according to their oral traditions. Sawa genealogies usually place Mbongo at the head of the lineage. Mbongo's son, usually given as Mbedi a Mbongo, lived at Piti, Cameroon on the Dibamba River. From there, Mbongo's grandsons migrated south toward the coast to found the various Sawa ethnic groups. Some stories make these migrants Mbongo's sons rather than grandsons.

Monneba, also spelled Moneba and other ways, was a local Duala leader on the Cameroon coast in the 1630s. Dutch sources from the 1660s say that Monneba ran a trading post on the Cameroons River at the present location of Douala. His people dealt primarily in ivory, with some slaves. Modern scholars equate Monneba with a Duala ruler named Mulobe a Ewale or Mulabe a Ewale. Assuming this is true, he is the earliest Duala leader of whom we have corroboration in written sources. It is quite possible that Monneba/Mulobe was the ruler who set into motion the transformation of the Duala into a trading people and the most influential ethnic group in early Cameroonian history.

George or Joss, born Doo a Makongo or Doo a Mukonga, was a king of the Duala people in the late 18th century. Doo a Makongo was the son of Makongo a Njo. He lived at Douala on the Wouri estuary on the coast of Cameroon. By 1788–1790, Doo was a powerful ruler in the area. During this time, the British slave trade was at its height, and Douala was the primary trading post in the region.

Kwane a Ngie, known in British records as Angua or Quan, was a Duala ruler from the Bonambela sublineage who flourished from 1788 to 1790 in Douala, Cameroon. The British slave trade was at its height at this time, and, although a rival ruler from the Bonanjo sublineage named George or Joss reigned simultaneously, British records point to Kwane as the more powerful or respected leader.

Priso a Doo, also known as Preshaw, Preese, and possibly Peter, was a Duala ruler who lived on the Wouri River of the Cameroons in the late 18th century. His violent behaviour lost him his birthright and catalysed the split of the Duala people into rival Bell and Akwa sublineages.

Rudolf Duala Manga Bell was a Duala king and resistance leader in the German colony of Kamerun (Cameroon). After being educated in both Kamerun and Europe, he succeeded his father Manga Ndumbe Bell on 2 September 1908.

Mundame or Moundamé is a community in Cameroon, in the Southwest Region, about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from the Mungo River. The river is navigable south of Mundame for about 100 kilometres (62 mi) as it flows through the coastal plain before entering mangrove swamps, where it splits into numerous small channels that empty into the Cameroon estuary complex.

Auguste Manga Ndumbe Bell was a leader of the Duala people of southern Cameroon from 1897 to 1908 during the period after the German colonialists assumed control of the region as the Kamerun colony.

Ndumbé Lobé Bell or King Bell was a leader of the Duala people in what is now the southern part of Cameroon during the period when the Germans established their colony of Kamerun. He was an astute politician and a highly successful businessman.

The Dibamba River is in the Littoral Region of southern Cameroon, emptying into the Cameroon estuary near the city of Doula.

Jantzen & Thormählen was a German firm based in Hamburg that was established to exploit the resources of Cameroon. The firm's commercial and political influence was a major factor in the establishment of the colony of Kamerun in 1884.