Related Research Articles

A false dilemma, also referred to as false dichotomy or false binary, is an informal fallacy based on a premise that erroneously limits what options are available. The source of the fallacy lies not in an invalid form of inference but in a false premise. This premise has the form of a disjunctive claim: it asserts that one among a number of alternatives must be true. This disjunction is problematic because it oversimplifies the choice by excluding viable alternatives, presenting the viewer with only two absolute choices when, in fact, there could be many.

In logic, equivocation is an informal fallacy resulting from the use of a particular word or expression in multiple senses within an argument.

A syllogism is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

A fallacy is the use of invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning in the construction of an argument that may appear to be well-reasoned if unnoticed. The term was introduced in the Western intellectual tradition by the Aristotelian De Sophisticis Elenchis.

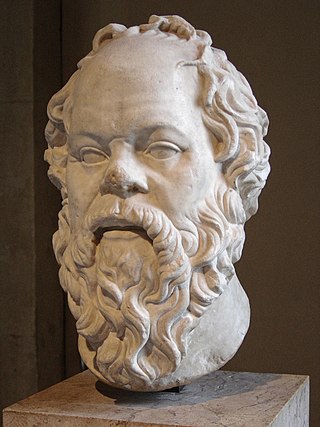

Deductive reasoning is the process of drawing valid inferences. An inference is valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, meaning that it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false. For example, the inference from the premises "all men are mortal" and "Socrates is a man" to the conclusion "Socrates is mortal" is deductively valid. An argument is sound if it is valid and all its premises are true. One approach defines deduction in terms of the intentions of the author: they have to intend for the premises to offer deductive support to the conclusion. With the help of this modification, it is possible to distinguish valid from invalid deductive reasoning: it is invalid if the author's belief about the deductive support is false, but even invalid deductive reasoning is a form of deductive reasoning.

Denying the antecedent, sometimes also called inverse error or fallacy of the inverse, is a formal fallacy of inferring the inverse from an original statement. It is a type of mixed hypothetical syllogism in the form:

In logic and formal semantics, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly by his followers, the Peripatetics. It was revived after the third century CE by Porphyry's Isagoge.

The fallacy of the undistributed middle is a formal fallacy that is committed when the middle term in a categorical syllogism is not distributed in either the minor premise or the major premise. It is thus a syllogistic fallacy.

An enthymeme is an argument with a hidden premise. Enthymemes are usually developed from premises that accord with the audience's view of the world and what is taken to be common sense. However, where the general premise of a syllogism is supposed to be true, making the subsequent deduction necessary, the general premise of an enthymeme is merely probable, which leads only to a tentative conclusion. Originally theorized by Aristotle, there are four types of enthymeme, at least two of which are described in Aristotle's work.

Logical reasoning is a mental activity that aims to arrive at a conclusion in a rigorous way. It happens in the form of inferences or arguments by starting from a set of premises and reasoning to a conclusion supported by these premises. The premises and the conclusion are propositions, i.e. true or false claims about what is the case. Together, they form an argument. Logical reasoning is norm-governed in the sense that it aims to formulate correct arguments that any rational person would find convincing. The main discipline studying logical reasoning is logic.

Illicit major is a formal fallacy committed in a categorical syllogism that is invalid because its major term is undistributed in the major premise but distributed in the conclusion.

Illicit minor is a formal fallacy committed in a categorical syllogism that is invalid because its minor term is undistributed in the minor premise but distributed in the conclusion.

The fallacy of exclusive premises is a syllogistic fallacy committed in a categorical syllogism that is invalid because both of its premises are negative.

Informal fallacies are a type of incorrect argument in natural language. The source of the error is not just due to the form of the argument, as is the case for formal fallacies, but can also be due to their content and context. Fallacies, despite being incorrect, usually appear to be correct and thereby can seduce people into accepting and using them. These misleading appearances are often connected to various aspects of natural language, such as ambiguous or vague expressions, or the assumption of implicit premises instead of making them explicit.

In logic and philosophy, a formal fallacy is a pattern of reasoning rendered invalid by a flaw in its logical structure that can neatly be expressed in a standard logic system, for example propositional logic. It is defined as a deductive argument that is invalid. The argument itself could have true premises, but still have a false conclusion. Thus, a formal fallacy is a fallacy in which deduction goes wrong, and is no longer a logical process. This may not affect the truth of the conclusion, since validity and truth are separate in formal logic.

A premise or premiss is a proposition—a true or false declarative statement—used in an argument to prove the truth of another proposition called the conclusion. Arguments consist of a set of premises and a conclusion.

An argument is a series of sentences, statements, or propositions some of which are called premises and one is the conclusion. The purpose of an argument is to give reasons for one's conclusion via justification, explanation, and/or persuasion.

In logic, specifically in deductive reasoning, an argument is valid if and only if it takes a form that makes it impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion nevertheless to be false. It is not required for a valid argument to have premises that are actually true, but to have premises that, if they were true, would guarantee the truth of the argument's conclusion. Valid arguments must be clearly expressed by means of sentences called well-formed formulas.

Negative conclusion from affirmative premises is a syllogistic fallacy committed when a categorical syllogism has a negative conclusion yet both premises are affirmative. The inability of affirmative premises to reach a negative conclusion is usually cited as one of the basic rules of constructing a valid categorical syllogism.

References

Notes

- ↑ Copi & Cohen 1990, pp. 206–207.

- ↑ Copi & Cohen 1990, pp. 214–217.

- ↑ Cogan 1998, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Copi & Cohen 1990, p. 206.

- ↑ Coffey 1912, pp. 302–304.

Books

- Coffey, Peter (1912). The Science of Logic. Vol. 1. Longmans, Green and Co.

- Cogan, Robert (1998). Critical Thinking . University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-1067-4.

- Copi, Irving M.; Cohen, Carl (1990). Introduction to Logic (8th ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-325035-4.