The first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus provides external information on some people and events found in the New Testament. The extant manuscripts of Josephus' book Antiquities of the Jews, written around AD 93–94, contain two references to Jesus of Nazareth and one reference to John the Baptist.

Argument from ignorance, or appeal to ignorance, is an informal fallacy where something is claimed to be true or false because of a lack of evidence to the contrary.

The Malleus Maleficarum, usually translated as the Hammer of Witches, is the best known treatise about witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer and first published in the German city of Speyer in 1486. Some describe it as the compendium of literature in demonology of the 15th century. Kramer presented his own views as the Roman Catholic Church's position.

The Roman historian and senator Tacitus referred to Jesus, his execution by Pontius Pilate, and the existence of early Christians in Rome in his final work, Annals, book 15, chapter 44.

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, better known in English as Pliny the Younger, was a lawyer, author, and magistrate of Ancient Rome. Pliny's uncle, Pliny the Elder, helped raise and educate him.

A fallacy is the use of invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning in the construction of an argument that may appear to be well-reasoned if unnoticed. The term was introduced in the Western intellectual tradition by the Aristotelian De Sophisticis Elenchis.

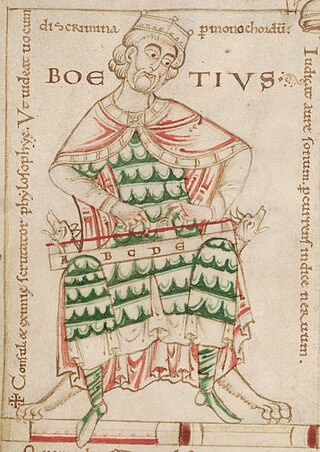

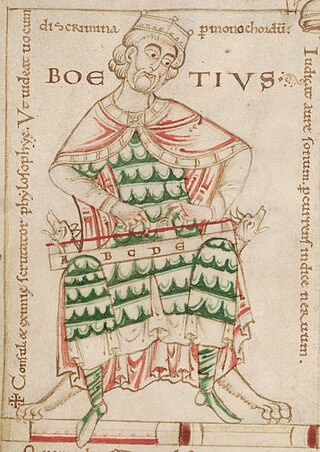

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known simply as Boethius, was a Roman senator, consul, magister officiorum, polymath, historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the translation of the Greek classics into Latin, a precursor to the Scholastic movement, and, along with Cassiodorus, one of the two leading Christian scholars of the 6th century. The local cult of Boethius in the Diocese of Pavia was sanctioned by the Sacred Congregation of Rites in 1883, confirming the diocese's custom of honouring him on the 23 October.

Earl J. Doherty is a Canadian author of The Jesus Puzzle (1999), Challenging the Verdict (2001), and Jesus: Neither God Nor Man (2009). Doherty argues for a version of the Christ myth theory, the thesis that Jesus did not exist as a historical figure. Doherty says that Paul thought of Jesus as a spiritual being executed in a spiritual realm.

The historicity of Jesus is the question of whether Jesus historically existed. The question of historicity was generally settled in scholarship in the early 20th century. Today scholars agree that a Jewish man named Jesus of Nazareth did exist in the Herodian Kingdom of Judea and the subsequent Herodian tetrarchy in the 1st century AD, upon whose life and teachings Christianity was later constructed, but a distinction is made by scholars between 'the Jesus of history' and 'the Christ of faith'.

The Historia Augusta is a late Roman collection of biographies, written in Latin, of the Roman emperors, their junior colleagues, designated heirs and usurpers from 117 to 284. Supposedly modeled on the similar work of Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, it presents itself as a compilation of works by six different authors, collectively known as the Scriptores Historiae Augustae, written during the reigns of Diocletian and Constantine I and addressed to those emperors or other important personages in Ancient Rome. The collection, as extant, comprises thirty biographies, most of which contain the life of a single emperor, but some include a group of two or more, grouped together merely because these emperors were either similar or contemporaneous.

In the fields of philosophy and mythography, euhemerism is an approach to the interpretation of mythology in which mythological accounts are presumed to have originated from real historical events or personages. Euhemerism supposes that historical accounts become myths as they are exaggerated in the retelling, accumulating elaborations and alterations that reflect cultural mores. It was named after the Greek mythographer Euhemerus, who lived in the late 4th century BC. In the more recent literature of myth, such as Bulfinch's Mythology, euhemerism is termed the "historical theory" of mythology.

The Christ myth theory, also known as the Jesus myth theory, Jesus mythicism, or the Jesus ahistoricity theory, is the fringe view that the story of Jesus is a work of mythology with no historical substance. Alternatively, in terms given by Bart Ehrman paraphrasing Earl Doherty, it is the view that "the historical Jesus did not exist. Or if he did, he had virtually nothing to do with the founding of Christianity."

Historical method is the collection of techniques and guidelines that historians use to research and write histories of the past. Secondary sources, primary sources and material evidence such as that derived from archaeology may all be drawn on, and the historian's skill lies in identifying these sources, evaluating their relative authority, and combining their testimony appropriately in order to construct an accurate and reliable picture of past events and environments.

The Augustinian hypothesis is a solution to the synoptic problem, which concerns the origin of the Gospels of the New Testament. The hypothesis holds that Matthew was written first, by Matthew the Evangelist. Mark the Evangelist wrote the Gospel of Mark second and used Matthew and the preaching of Peter as sources. Luke the Evangelist wrote the Gospel of Luke and was aware of the two Gospels that preceded him. Unlike some competing hypotheses, this hypothesis does not rely on, nor does it argue for, the existence of any document that is not explicitly mentioned in historical testimony. Instead, the hypothesis draws primarily upon historical testimony, rather than textual criticism, as the central line of evidence. The foundation of evidence for the hypothesis is the writings of the Church Fathers: historical sources dating back to as early as the first half of the 2nd century, which have been held as authoritative by most Christians for nearly two millennia. Adherents to the Augustinian hypothesis view it as a simple, coherent solution to the synoptic problem.

The Frisii were an ancient tribe, living in the low-lying region between the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and the River Ems, sharing some cultural and linguistic elements with the neighbouring Celts. The newly formed marshlands were largely uninhabitated until the 6th or 5th centuries BC, when inland settlers started to colonize the area. As sea levels rose and flooding risks increased, the inhabitants learned to build their houses on village mounds or terps. The way of life and material culture of the Frisii hardly distinguished itself from the customs of the Chaucian tribes living farther east. The latter, however, were considered to be part of the Germanic tribal confederation.

History is the systematic study and documentation of the past. History is an academic discipline which uses a narrative to describe, examine, question, and analyse past events, and investigate their patterns of cause and effect. Historians debate which narrative best explains an event, as well as the significance of different causes and effects. Historians debate the nature of history as an end in itself, and its usefulness in giving perspective on the problems of the present.

Christians were persecuted throughout the Roman Empire, beginning in the 1st century AD and ending in the 4th century. Originally a polytheistic empire in the traditions of Roman paganism and the Hellenistic religion, as Christianity spread through the empire, it came into ideological conflict with the imperial cult of ancient Rome. Pagan practices such as making sacrifices to the deified emperors or other gods were abhorrent to Christians as their beliefs prohibited idolatry. The state and other members of civic society punished Christians for treason, various rumored crimes, illegal assembly, and for introducing an alien cult that led to Roman apostasy. The first, localized Neronian persecution occurred under Emperor Nero in Rome. A number of mostly localized persecutions occurred during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. After a lull, persecution resumed under Emperors Decius and Trebonianus Gallus. The Decian persecution was particularly extensive. The persecution of Emperor Valerian ceased with his notable capture by the Sasanian Empire's Shapur I at the Battle of Edessa during the Roman–Persian Wars. His successor, Gallienus, halted the persecutions.

Evidence of absence is evidence of any kind that suggests something is missing or that it does not exist. What counts as evidence of absence has been a subject of debate between scientists and philosophers. It is often distinguished from absence of evidence.

Christian sources such as the New Testament books in the Christian Bible, include detailed accounts about Jesus, but scholars differ on the historicity of specific episodes described in the biblical accounts of Jesus. The only two events subject to "almost universal assent" are that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist and was crucified by the order of the Roman Prefect Pontius Pilate.

A letter collection consists of a publication, usually a book, containing a compilation of letters written by a real person. Unlike an epistolary novel, a letter collection belongs to non-fiction literature. As a publication, a letter collection is distinct from an archive, which is a repository of original documents.