Lipolysis is the metabolic pathway through which lipid triglycerides are hydrolyzed into a glycerol and free fatty acids. It is used to mobilize stored energy during fasting or exercise, and usually occurs in fat adipocytes. The most important regulatory hormone in lipolysis is insulin; lipolysis can only occur when insulin action falls to low levels, as occurs during fasting. Other hormones that affect lipolysis include leptin, glucagon, epinephrine, norepinephrine, growth hormone, atrial natriuretic peptide, brain natriuretic peptide, and cortisol.

Adipose tissue is a loose connective tissue composed mostly of adipocytes. It also contains the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of cells including preadipocytes, fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells and a variety of immune cells such as adipose tissue macrophages. Its main role is to store energy in the form of lipids, although it also cushions and insulates the body.

Adipocytes, also known as lipocytes and fat cells, are the cells that primarily compose adipose tissue, specialized in storing energy as fat. Adipocytes are derived from mesenchymal stem cells which give rise to adipocytes through adipogenesis. In cell culture, adipocyte progenitors can also form osteoblasts, myocytes and other cell types.

Adiponectin is a protein hormone and adipokine, which is involved in regulating glucose levels and fatty acid breakdown. In humans, it is encoded by the ADIPOQ gene and is produced primarily in adipose tissue, but also in muscle and even in the brain.

Perilipin, also known as lipid droplet-associated protein, perilipin 1, or PLIN, is a protein that, in humans, is encoded by the PLIN gene. The perilipins are a family of proteins that associate with the surface of lipid droplets. Phosphorylation of perilipin is essential for the mobilization of fats in adipose tissue.

In chemistry, de novo synthesis is the synthesis of complex molecules from simple molecules such as sugars or amino acids, as opposed to recycling after partial degradation. For example, nucleotides are not needed in the diet as they can be constructed from small precursor molecules such as formate and aspartate. Methionine, on the other hand, is needed in the diet because while it can be degraded to and then regenerated from homocysteine, it cannot be synthesized de novo.

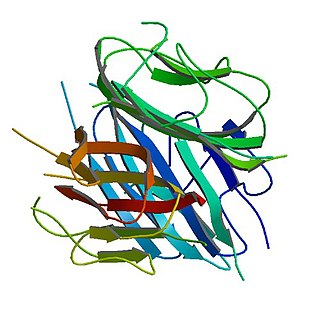

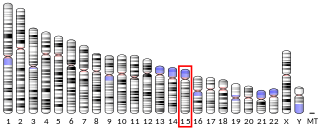

Hormone-sensitive lipase (EC 3.1.1.79, HSL), also previously known as cholesteryl ester hydrolase (CEH), sometimes referred to as triacylglycerol lipase, is an enzyme that, in humans, is encoded by the LIPE gene, and catalyzes the following reaction:

White adipose tissue or white fat is one of the two types of adipose tissue found in mammals. The other kind is brown adipose tissue. White adipose tissue is composed of monolocular adipocytes.

FABP1 is a human gene coding for the protein product FABP1. It is also frequently known as liver-type fatty acid-binding protein (LFABP).

Adipose differentiation-related protein, also known as perilipin 2, ADRP or adipophilin, is a protein which belongs to the perilipin (PAT) family of cytoplasmic lipid droplet (CLD)–binding proteins. In humans it is encoded by the ADFP gene. This protein surrounds the lipid droplet along with phospholipids and is involved in assisting the storage of neutral lipids within the lipid droplets.

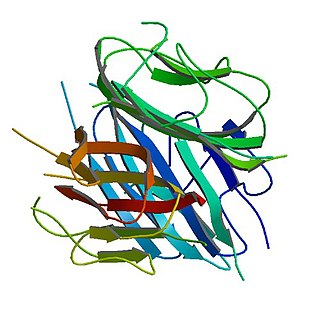

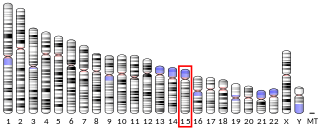

Adipose triglyceride lipase, also known as patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 2 and ATGL, is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the PNPLA2 gene. ATGL catalyses the first reaction of lipolysis, where triacylglycerols are hydrolysed to diacylglycerols.

Replication initiator 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the REPIN1 gene. The protein helps enable RNA binding activity as a replication initiation-region protein. The make up of REPIN 1 include three zinc finger hand clusters that organize polydactyl zinc finger proteins containing 15 zinc finger DNA- binding motifs. It has also been predicted to help in regulation of transcription via RNA polymerase II with it being located in the nucleoplasm. Expression of this protein has been seen in the colon, spleen, kidney, and 23 other tissues within the human body throughout.

Fibroblast growth factor 21 is a protein that in mammals is encoded by the FGF21 gene. The protein encoded by this gene is a member of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family and specifically a member of the endocrine subfamily which includes FGF23 and FGF15/19. FGF21 is the primary endogenous agonist of the FGF21 receptor, which is composed of the co-receptors FGF receptor 1 and β-Klotho.

Lipid droplets, also referred to as lipid bodies, oil bodies or adiposomes, are lipid-rich cellular organelles that regulate the storage and hydrolysis of neutral lipids and are found largely in the adipose tissue. They also serve as a reservoir for cholesterol and acyl-glycerols for membrane formation and maintenance. Lipid droplets are found in all eukaryotic organisms and store a large portion of lipids in mammalian adipocytes. Initially, these lipid droplets were considered to merely serve as fat depots, but since the discovery in the 1990s of proteins in the lipid droplet coat that regulate lipid droplet dynamics and lipid metabolism, lipid droplets are seen as highly dynamic organelles that play a very important role in the regulation of intracellular lipid storage and lipid metabolism. The role of lipid droplets outside of lipid and cholesterol storage has recently begun to be elucidated and includes a close association to inflammatory responses through the synthesis and metabolism of eicosanoids and to metabolic disorders such as obesity, cancer, and atherosclerosis. In non-adipocytes, lipid droplets are known to play a role in protection from lipotoxicity by storage of fatty acids in the form of neutral triacylglycerol, which consists of three fatty acids bound to glycerol. Alternatively, fatty acids can be converted to lipid intermediates like diacylglycerol (DAG), ceramides and fatty acyl-CoAs. These lipid intermediates can impair insulin signaling, which is referred to as lipid-induced insulin resistance and lipotoxicity. Lipid droplets also serve as platforms for protein binding and degradation. Finally, lipid droplets are known to be exploited by pathogens such as the hepatitis C virus, the dengue virus and Chlamydia trachomatis among others.

Lipotoxicity is a metabolic syndrome that results from the accumulation of lipid intermediates in non-adipose tissue, leading to cellular dysfunction and death. The tissues normally affected include the kidneys, liver, heart and skeletal muscle. Lipotoxicity is believed to have a role in heart failure, obesity, and diabetes, and is estimated to affect approximately 25% of the adult American population.

Adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) comprise tissue resident macrophages present in adipose tissue. Adipose tissue apart from adipocytes is composed of the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of cells including preadipocytes, fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells and variety of immune cells. The latter ones are composed of mast cells, eosinophils, B cells, T cells and macrophages. The number of macrophages within adipose tissue differs depending on the metabolic status. As discovered by Rudolph Leibel and Anthony Ferrante et al. in 2003 at Columbia University, the percentage of macrophages within adipose tissue ranges from 10% in lean mice and humans up to 50% in extremely obese, leptin deficient mice and almost 40% in obese humans. Increased number of adipose tissue macrophages correlates with increased adipose tissue production of proinflammatory molecules and might therefore contribute to the pathophysiological consequences of obesity.

Gökhan S. Hotamisligil is a Turkish-American physician scientist; James Stevens Simmons Chair of Genetics and Metabolism at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH); Director of the Sabri Ülker Center for Metabolic Research and associate member of Harvard-MIT Broad Institute, Harvard Stem Cell Institute and the Joslin Diabetes Center.

Hepatokines are proteins produced by liver cells (hepatocytes) that are secreted into the circulation and function as hormones across the organism. Research is mostly focused on hepatokines that play a role in the regulation of metabolic diseases such as diabetes and fatty liver and include: Adropin, ANGPTL4, Fetuin-A, Fetuin-B, FGF-21, Hepassocin, LECT2, RBP4,Selenoprotein P, Sex hormone-binding globulin.

Bing Li is an immunologist, researcher, and academic. He is an Endowed Professor for Cancer Immunology, a professor of Pathology at the University of Iowa, and the Director of Iowa Cancer and Obesity Initiative. He is also the founder of BMImmune Inc.

Apoptosis inhibitor of macrophage (AIM) is a protein produced by macrophages that regulates immune responses and inflammation. It plays a crucial role in key intracellular processes like lipid metabolism and apoptosis.