| Gargaphia solani | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hemiptera |

| Suborder: | Heteroptera |

| Family: | Tingidae |

| Genus: | Gargaphia |

| Species: | G. solani |

| Binomial name | |

| Gargaphia solani Heidemann, 1914 [1] | |

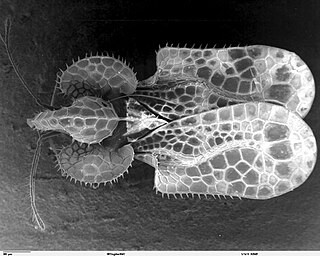

Gargaphia solani is a subsocial species of lace bug commonly known as the eggplant lace bug. The species was described by Heidemann in 1914 [1] after it aroused attention a year earlier in the United States as an eggplant pest around Norfolk, Virginia. [2] Fink found that the species became an agricultural pest when eggplant is planted on a large scale. [2]

Contents

It mainly feeds on the flowering plant family Solanaceae, being found on a range of Solanum species including tomato, potatoes and eggplant as well as species of other genera such as Althara , Cassia, Gossypium and Salvia . It is found in Mexico, the United States and Canada. [3] It is prey to generalist predators such as adults and larvae of the ladybirds Hippodamia convergens and Megilla maculata , which flip their prey onto their back before eating them. Some other heteropterans prey on them, specifically Podisus maculiventris and Orius insidiosus (which prey on nymphs). Three small spider species are also known to feed on this species. [4]

Mothers lay their eggs in circular deposits on the abaxial (lower) side of leaves; eggs are "attached at a slight angle and covered with frass". [4] The species goes through five instars in its life cycle, and the fifth instar and adult form were included as figures in Fink (1915). [2] The developmental process from egg to adult takes about 20 days, the nymphal stage taking about 10 days. [4] Fink noticed that the nymphs have spines, though he was not entirely sure why (more recent work has shed light on their function). [5] Mating was observed to occur in November and there are perhaps seven or eight generations each year. [4] These may occur on eggplant for the first six and the last on horse nettle ( Solanum carolinense ). [4] Adults have been found year-round in Missouri, sometimes while hibernating in clumps of grass or under bark or the leaves of mullein ( Verbascum thapsus ). [6]

This was the first species in the family Tingidae (lace bugs) in which maternal care was discovered. [2] [7] Mothers defend their offspring against predators as they mature by moving towards the threat and fanning their wings. [8] Experiments show that without this protection their progeny have only a 3% survival rate in the wild. [8] Further observation has shown that guarding eggs and protecting offspring after they hatch has a significant cost to the mother, reducing her future reproductive potential in terms of fecundity and clutch number. [9] Evolutionary theory predicts that parental investment should change depending on the reproductive value of offspring and future reproductive potential of parents. Douglas Tallamy found that maternal defensive behaviour in this species is consistent with the theory, since mothers became more aggressive in their clutch defense as they got older (less future reproduction at risk) and as the nymphs in each clutch matured (greater investment lost/higher survival potential as they get bigger). [10] Because of heavy predation, this investment is necessary. However, females can reduce costs to themselves by laying in the egg masses of conspecifics (i.e. other mothers) who will then take care of their offspring for them (similar behaviour occurs in other species; see brood parasite). This exploitation of other females is common; eggs are laid in neighbouring egg masses whenever there is opportunity to do so. [11] Egg dumpers were observed to have higher mortality rates per egg, but were at an advantage because they were more fecund (could lay more eggs) and were at lower risk of predation. [12]

Some semiochemicals have been identified for this species. [13] For example, larvae emit an alarm pheromone called geraniol from dorsal glands which cause nearby nymphs to flee, [5] which explains earlier observations that nymphs become alarmed when a nearby sibling is crushed. [14]