The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Nuclear physicist Robert Oppenheimer was the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory that designed the actual bombs. The Army component of the project was designated the Manhattan District as its first headquarters were in Manhattan; the placename gradually superseded the official codename, Development of Substitute Materials, for the entire project. Along the way, the project absorbed its earlier British counterpart, Tube Alloys. The Manhattan Project began modestly in 1939, but grew to employ more than 130,000 people and cost nearly US$2 billion. Over 90 percent of the cost was for building factories and to produce fissile material, with less than 10 percent for development and production of the weapons. Research and production took place at more than thirty sites across the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the British efforts were kept classified, and as such had to be referred to by code even within the highest circles of government.

Operation Hurricane was the first test of a British atomic device. A plutonium implosion device was detonated on 3 October 1952 in Main Bay, Trimouille Island in the Montebello Islands in Western Australia. With the success of Operation Hurricane, Britain became the third nuclear power after the United States and the Soviet Union.

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was signed by Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt on 19 August 1943, during World War II, at the First Quebec Conference in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada.

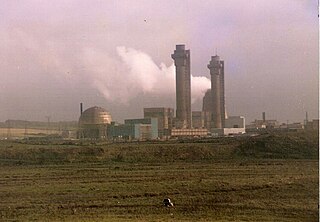

The Windscale fire of 10 October 1957 was the worst nuclear accident in the United Kingdom's history, and one of the worst in the world, ranked in severity at level 5 out of a possible 7 on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The fire was in Unit 1 of the two-pile Windscale site on the north-west coast of England in Cumberland. The two graphite-moderated reactors, referred to at the time as "piles," had been built as part of the British post-war atomic bomb project. Windscale Pile No. 1 was operational in October 1950, followed by Pile No. 2 in June 1951.

In 1952, the United Kingdom became the third country to develop and test nuclear weapons, and is one of the five nuclear-weapon states under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

The US–UK Mutual Defense Agreement, or 1958 UK–US Mutual Defence Agreement, is a bilateral treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom on nuclear weapons co-operation. The treaty's full name is Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland for Cooperation on the uses of Atomic Energy for Mutual Defense Purposes. It allows the US and the UK to exchange nuclear materials, technology and information. The US has nuclear co-operation agreements with other countries, including France and other NATO countries, but this agreement is by far the most comprehensive. Because of the agreement's strategic value to Britain, Harold Macmillan called it "the Great Prize".

The Manhattan Project was a research and development project that produced the first atomic bombs during World War II. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army Corps of Engineers. The Army component of the project was designated the Manhattan District; "Manhattan" gradually became the codename for the entire project. Along the way, the project absorbed its earlier British counterpart, Tube Alloys. The Manhattan Project began modestly in 1939, but grew to employ more than 130,000 people and cost nearly US$2 billion. Over 90% of the cost was for building factories and producing the fissionable materials, with less than 10% for development and production of the weapons.

The MAUD Committee was a British scientific working group formed during the Second World War. It was established to perform the research required to determine if an atomic bomb was feasible. The name MAUD came from a strange line in a telegram from Danish physicist Niels Bohr referring to his housekeeper, Maud Ray.

The X-10 Graphite Reactor is a decommissioned nuclear reactor at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Formerly known as the Clinton Pile and X-10 Pile, it was the world's second artificial nuclear reactor, and the first designed and built for continuous operation. It was built during World War II as part of the Manhattan Project.

Operation Totem was a pair of British atmospheric nuclear tests which took place at Emu Field in South Australia in October 1953. They followed the Operation Hurricane test of the first British atomic bomb, which had taken place at the Montebello Islands a year previously. The main purpose of the trial was to determine the acceptable limit on the amount of plutonium-240 which could be present in a bomb.

The Montreal Laboratory in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, was established by the National Research Council of Canada during World War II to undertake nuclear research in collaboration with the United Kingdom, and to absorb some of the scientists and work of the Tube Alloys nuclear project in Britain. It became part of the Manhattan Project, and designed and built some of the world's first nuclear reactors.

Sir John Philip Baxter, better known as Philip Baxter, was a British chemical engineer. He was the second director of the University of New South Wales from 1953, continuing as vice-chancellor when the position's title was changed in 1955. Under his administration, the university grew from its technical college roots into the "fastest growing and most rapidly diversifying tertiary institution in Australia". Philip Baxter College is named in his honour.

Project-706, also known as Project-786 was the codename of a research and development program to develop Pakistan's first nuclear weapons. The program was initiated by Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in 1974 in response to the Indian nuclear tests conducted in May 1974. During the course of this program, Pakistani nuclear scientists and engineers developed the requisite nuclear infrastructure and gained expertise in the extraction, refining, processing and handling of fissile material with the ultimate goal of designing a nuclear device. These objectives were achieved by the early 1980s with the first successful cold test of a Pakistani nuclear device in 1983. The two institutions responsible for the execution of the program were the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission and the Kahuta Research Laboratories, led by Munir Ahmed Khan and Abdul Qadeer Khan respectively. In 1976 an organization called Special Development Works (SDW) was created within the Pakistan Army, directly under the Chief of the Army Staff (Pakistan) (COAS). This organization worked closely with PAEC and KRL to secretly prepare the nuclear test sites in Baluchistan and other required civil infrastructure.

Following the success of Operation Grapple in which the United Kingdom became the third nation to acquire thermonuclear weapons after the United States and the Soviet Union, Britain launched negotiations with the US on a treaty under in which both could share information and material to design, test and maintain their nuclear weapons. This effort culminated in the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement. One of the results of that treaty was that Britain was allowed to use United States' Nevada Test Site for testing their designs and ideas, and received full support from the personnel there, in exchange for the data "take" from the experiment, a mutual condition. In effect the Nevada Test Site became Britain's test ground, subject only to advance planning and integrating their testing into that of the United States. This resulted in 24 underground tests at the Nevada Test Site from 1958 through the end of nuclear testing in the US in September 1992.

After World War II, Sweden considered building nuclear weapons to defend themselves against an offensive assault from the Soviet Union. From 1945 to 1972 the government ran a clandestine nuclear weapons program under the guise of civilian defense research at the Swedish National Defence Research Institute (FOA).

Britain contributed to the Manhattan Project by helping initiate the effort to build the first atomic bombs in the United States during World War II, and helped carry it through to completion in August 1945 by supplying crucial expertise. Following the discovery of nuclear fission in uranium, scientists Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch at the University of Birmingham calculated, in March 1940, that the critical mass of a metallic sphere of pure uranium-235 was as little as 1 to 10 kilograms, and would explode with the power of thousands of tons of dynamite. The Frisch–Peierls memorandum prompted Britain to create an atomic bomb project, known as Tube Alloys. Mark Oliphant, an Australian physicist working in Britain, was instrumental in making the results of the British MAUD Report known in the United States in 1941 by a visit in person. Initially the British project was larger and more advanced, but after the United States entered the war, the American project soon outstripped and dwarfed its British counterpart. The British government then decided to shelve its own nuclear ambitions, and participate in the American project.

The British hydrogen bomb programme was the ultimately successful British effort to develop hydrogen bombs between 1952 and 1958. During the early part of the Second World War, Britain had a nuclear weapons project, codenamed Tube Alloys. At the Quebec Conference in August 1943, British prime minister Winston Churchill and United States president Franklin Roosevelt signed the Quebec Agreement, merging Tube Alloys into the American Manhattan Project, in which many of Britain's top scientists participated. The British government trusted that America would share nuclear technology, which it considered to be a joint discovery, but the United States Atomic Energy Act of 1946 ended technical cooperation. Fearing a resurgence of American isolationism, and the loss of Britain's great power status, the British government resumed its own development effort, which was codenamed "High Explosive Research".

High Explosive Research (HER) was the British project to develop atomic bombs independently after the Second World War. This decision was taken by a cabinet sub-committee on 8 January 1947, in response to apprehension of an American return to isolationism, fears that Britain might lose its great power status, and the actions by the United States to withdraw unilaterally from sharing of nuclear technology under the 1943 Quebec Agreement. The decision was publicly announced in the House of Commons on 12 May 1948.

The Windscale Piles were a pair of air-cooled graphite-moderated nuclear reactors on the northwest coast of England in Cumberland. The two reactors, referred to at the time as "piles", were built as part of the British post-war atomic bomb project.