Rhythm generally means a "movement marked by the regulated succession of strong and weak elements, or of opposite or different conditions". This general meaning of regular recurrence or pattern in time can apply to a wide variety of cyclical natural phenomena having a periodicity or frequency of anything from microseconds to several seconds ; to several minutes or hours, or, at the most extreme, even over many years.

Music theory is the study of theoretical frameworks for understanding the practices and possibilities of music. The Oxford Companion to Music describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory": The first is the "rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation ; the second is learning scholars' views on music from antiquity to the present; the third is a sub-topic of musicology that "seeks to define processes and general principles in music". The musicological approach to theory differs from music analysis "in that it takes as its starting-point not the individual work or performance but the fundamental materials from which it is built."

In music, metre or meter refers to regularly recurring patterns and accents such as bars and beats. Unlike rhythm, metric onsets are not necessarily sounded, but are nevertheless implied by the performer and expected by the listener.

Musical analysis is the study of musical structure in either compositions or performances. According to music theorist Ian Bent, music analysis "is the means of answering directly the question 'How does it work?'". The method employed to answer this question, and indeed exactly what is meant by the question, differs from analyst to analyst, and according to the purpose of the analysis. According to Bent, "its emergence as an approach and method can be traced back to the 1750s. However it existed as a scholarly tool, albeit an auxiliary one, from the Middle Ages onwards."

Schenkerian analysis is a method of analyzing tonal music based on the theories of Heinrich Schenker (1868–1935). The goal is to demonstrate the organic coherence of the work by showing how the "foreground" relates to an abstracted deep structure, the Ursatz. This primal structure is roughly the same for any tonal work, but a Schenkerian analysis shows how, in each individual case, that structure develops into a unique work at the foreground. A key theoretical concept is "tonal space". The intervals between the notes of the tonic triad in the background form a tonal space that is filled with passing and neighbour tones, producing new triads and new tonal spaces that are open for further elaborations until the "surface" of the work is reached.

In poetic and musical meter, and by analogy in publishing, an anacrusis is a brief introduction. In music, it is also known as a pickup beat, or fractional pick-up, i.e. a note or sequence of notes, a motif, which precedes the first downbeat in a bar in a musical phrase.

Generative grammar is a research tradition in linguistics that aims to explain the cognitive basis of language by formulating and testing explicit models of humans' subconscious grammatical knowledge. Generative linguists, or generativists, tend to share certain working assumptions such as the competence–performance distinction and the notion that some domain-specific aspects of grammar are partly innate in humans. These assumptions are rejected in non-generative approaches such as usage-based models of language. Generative linguistics includes work in core areas such as syntax, semantics, phonology, psycholinguistics, and language acquisition, with additional extensions to topics including biolinguistics and music cognition.

Generative music is a term popularized by Brian Eno to describe music that is ever-different and changing, and that is created by a system.

Alfred Whitford (Fred) Lerdahl is an American music theorist and composer. Best known for his work on musical grammar, cognition, rhythmic theory and pitch space, he and the linguist Ray Jackendoff developed the Chomsky-inspired generative theory of tonal music.

Ray Jackendoff is an American linguist. He is professor of philosophy, Seth Merrin Chair in the Humanities and, with Daniel Dennett, co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University. He has always straddled the boundary between generative linguistics and cognitive linguistics, committed to both the existence of an innate universal grammar and to giving an account of language that is consistent with the current understanding of the human mind and cognition.

In music theory, prolongation is the process in tonal music through which a pitch, interval, or consonant triad is considered to govern spans of music when not physically sounding. It is a central principle in the music-analytic methodology of Schenkerian analysis, conceived by Austrian theorist Heinrich Schenker. The English term usually translates Schenker's Auskomponierung. According to Fred Lerdahl, "The term 'prolongation' [...] usually means 'composing out' ."

"Cognitive Constraints on Compositional Systems" is an essay by Fred Lerdahl that cites Pierre Boulez's Le Marteau sans maître (1955) as an example of "a huge gap between compositional system and cognized result," though he "could have illustrated just as well with works by Milton Babbitt, Elliott Carter, Luigi Nono, Karlheinz Stockhausen, or Iannis Xenakis". To explain this gap, and in hopes of bridging it, Lerdahl proposes the concept of a musical grammar, "a limited set of rules that can generate indefinitely large sets of musical events and/or their structural descriptions". He divides this further into compositional grammar and listening grammar, the latter being one "more or less unconsciously employed by auditors, that generates mental representations of the music". He divides the former into natural and artificial compositional grammars. While the two have historically been fruitfully mixed, a natural grammar arises spontaneously in a culture while an artificial one is a conscious invention of an individual or group in a culture; the gap can arise only between listening grammar and artificial grammars. To begin to understand the listening grammar, Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff created a theory of musical cognition, A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. That theory is outlined in the essay.

Music semiology (semiotics) is the study of signs as they pertain to music on a variety of levels.

In music cognition and musical analysis, the study of melodic expectation considers the engagement of the brain's predictive mechanisms in response to music. For example, if the ascending musical partial octave "do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-..." is heard, listeners familiar with Western music will have a strong expectation to hear or provide one more note, "do", to complete the octave.

In music theory, pitch-class space is the circular space representing all the notes in a musical octave. In this space, there is no distinction between tones separated by an integral number of octaves. For example, C4, C5, and C6, though different pitches, are represented by the same point in pitch class space.

Cognitive musicology is a branch of cognitive science concerned with computationally modeling musical knowledge with the goal of understanding both music and cognition.

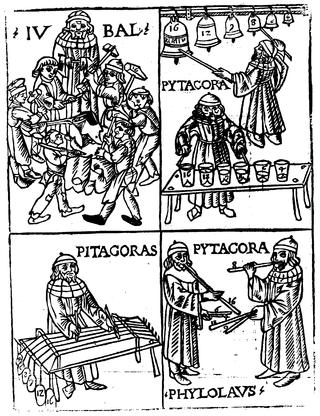

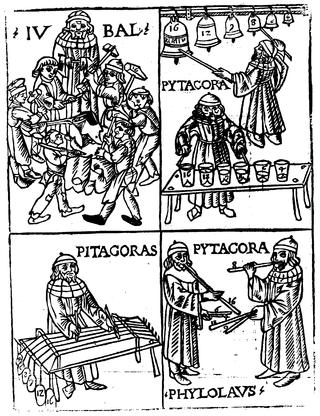

A bell pattern is a rhythmic pattern of striking a hand-held bell or other instrument of the idiophone family, to make it emit a sound at desired intervals. It is often a key pattern, in most cases it is a metal bell, such as an agogô, gankoqui, or cowbell, or a hollowed piece of wood, or wooden claves. In band music, bell patterns are also played on the metal shell of the timbales, and drum kit cymbals.

In music, a cross-beat or cross-rhythm is a specific form of polyrhythm. The term cross rhythm was introduced in 1934 by the musicologist Arthur Morris Jones (1889–1980). It refers to a situation where the rhythmic conflict found in polyrhythms is the basis of an entire musical piece.

Irène Deliège was a Belgian musician and cognitive scientist. She was born in January 1933 in Flanders, but spent most of her life in French-speaking Brussels and Liège, Belgium. She was noted for her theory of Cue Abstraction, and for her work in establishing the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music. She died on 11th May 2024 in Brussels.

This is a glossary of Schenkerian analysis, a method of musical analysis of tonal music based on the theories of Heinrich Schenker (1868–1935). The method is discussed in the concerned article and no attempt is made here to summarize it. Similarly, the entries below whenever possible link to other articles where the concepts are described with more details, and the definitions are kept here to a minimum.